水资源控制、物品交换和礼仪:新墨西哥州查科峡谷普韦布洛博尼托遗址的考古发掘

Investigating Water Control, Exchange, and Ritual through Excavations of Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico

帕特丽夏·科朗 Patricia L. Crown

伍尔特·威尔斯 W.H. Wills

(美国新墨哥大学人类学系 Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, USA)

普韦布洛博尼托是位于美国新墨西哥州西北部查科峡谷的一个大型砖石城镇,地处海拔1890米。该遗址是查科文化国家历史公园的一部分,已被列入联合国教科文组织世界遗产,集中分布有多达400个遗址点,时间跨度从自古印第安人时期到纳瓦霍历史时期。最为突出的特点被称为查克现象(950AD-1140AD):以广泛分布在美国西南部四角地(科罗拉多州、犹他州、亚利桑那州和新墨西哥州交界处)的多层次砖石建筑与比邻的道路系统为代表。

普韦布洛博尼托博尼托遗址是美国西南地区最大、也是最为完整的考古学发掘遗址,包括大约600个砖石房址,其中有4层楼建筑,也有大约37个用于仪式活动的半地下砖石结构(kivas) 。 普韦布洛博尼托遗址的发掘主要以两个项目为主导: 从1896年至1899年,海德探险考察队(HEE)在理查德·维特尔和乔治·派普尔的带领下发掘了大约200个房间;在1921年至1927年期间,国家地理学会(NGS)资助了尼尔·贾德(Neil Judd),在他的带领下发掘了遗址剩余部分。虽然遗址在1927年已被发掘,但关于遗址的建造顺序、水资源供给、人群间的互动和社会领导层的性质等问题都不甚明了。

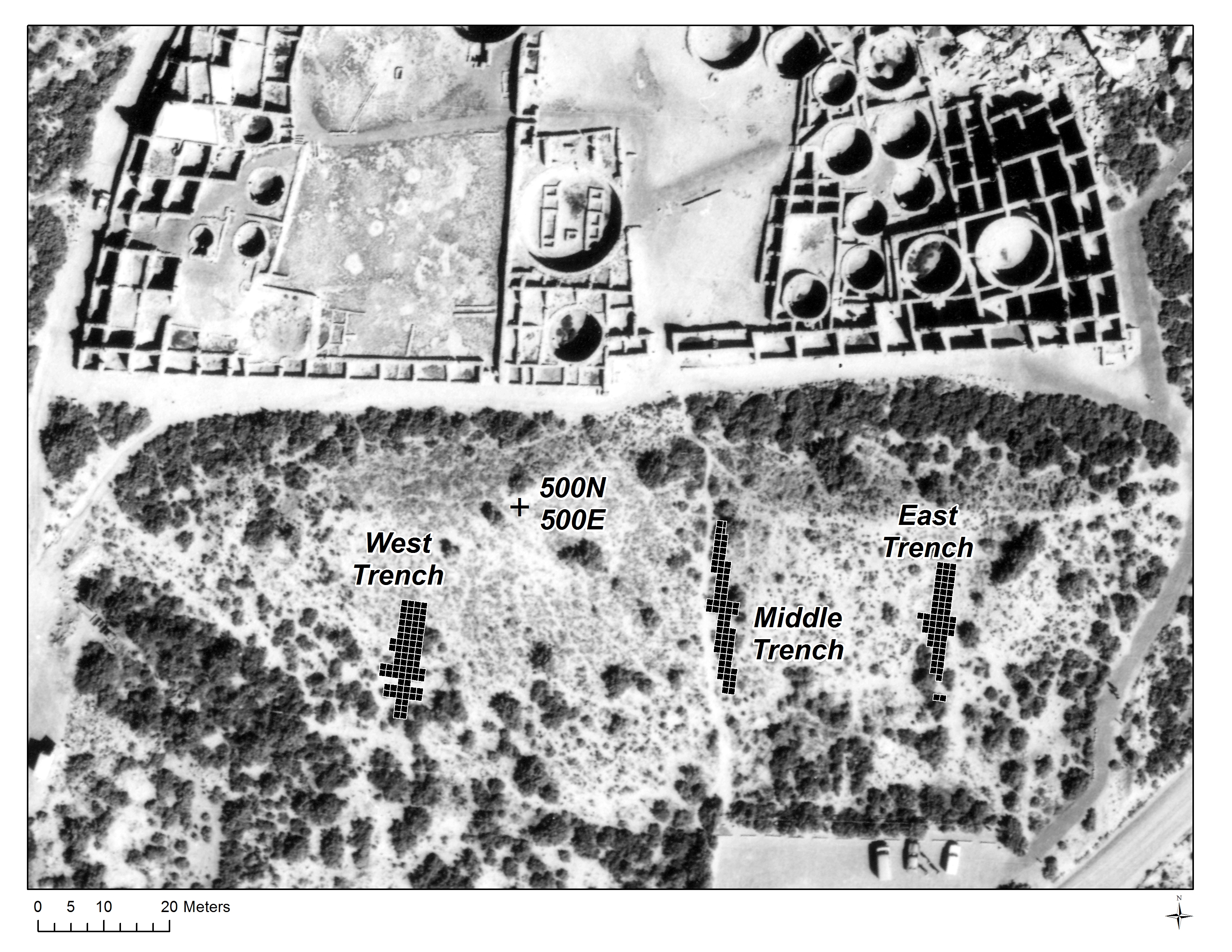

为了解决这些研究问题,我们自2004年开始了一系列项目,重新清理发掘先前由HEE或NGS项目揭露的部分单位。所有这些新项目都与查科文化后裔的原住民部落进行了咨询与商讨。这些项目也都由本科生和研究生(包括许多美国原住民学生)、以及技术专家直接参与。在美国国家科学基金会(NSF)和NGS的资助下,威尔斯在2004年至2007年期间,重新部分清理了由NGS先前在普韦布洛博尼托遗址南部位于两个垃圾丘之间发掘的三个探方。我们的研究目标是通过对地下水利系统的揭露以了解公元1000年左右普韦布洛博尼托遗址的发展情况与水资源控制的关系。该项目希望通过记录地层信息、放射线碳测年样品和指征环境变化样品的采集等工作来回答这个问题。项目结果显示,公元11世纪左右,普韦布洛博尼托遗址居民在在聚落南部建造了一个巨大的沟渠。沟渠中的沉积物分析反映出多次的洪水事件,表明该沟渠的建造主要是为了建筑和家庭用水,并将洪水从居住地分流出去。这个沟渠在公元1000年后段被侵蚀破坏。

仅仅在重新发掘这些探方的几个小时内,我们意识到NGS人员把大部分文物在发掘中就直接回填到探方中,因此我们现在至少拥有超过20万件遗物。在NSF的额外资金支持下,科朗在2007年至2009年期间聘请了12名研究生和本科生对这些材料进行分析。该项目的成果最近发表在科朗主编《查科峡谷普韦布洛博尼托遗址》。研究中发现了五片陶片似乎是普韦布洛博尼托博尼托遗址罕见的形式,被考古学家称为“圆筒罐”。这些体高且直肩的罐子有时是白色背景上有黑色图案、亦有通体白色或红色的设计。 科朗希望了解这些圆筒罐的用途,是否与玛雅文化中饮用巧克力奶的功用相似。因此,她与合作者赫斯特(W. Jeffrey Hurst)采用高效液相色谱-质谱仪对这五片陶片进行分析,在其中的三片陶片发现巧克力残留物。这一研究表明从中美洲到美国西南部的亚热带地区存在着长距离的可可豆贸易或交换。与此同时,普韦布洛博尼托博尼托遗址居民不仅从中美洲获得可可豆,而且从南部获得猩红色的金刚鹦鹉、铜、掐丝珐琅和其他鸟类和羽毛的外来物。那么,普韦布洛博尼托居民以什么作为交换呢?我们并没有确切的答案,但有几位学者认为绿松石饰物可能可以用于交换中美洲的舶来品。

巧克力残留物的发现促使科朗申请重新发掘房址28号,该房址在1896年发现了已知大约200个圆筒罐中的112个。在重新发掘之前,探地雷达证实遗存保存完好,在较低楼层的柱子仍保存在原地。在美国人文科学基金会(NEH)和NGS的资助下,由六名研究生和本科生参与,我们在2013年用六周的时间重新发掘了该房址。我们确定了该房屋的烧毁原因和时间、圆筒罐的出土地点、以及HEE项目的发掘面。 遗址公园还允许我们向下继续发掘,以确定查科峡谷普韦布洛博尼托遗址这一区域的发展和使用。

我们了解到,比邻的居民最初将这个空间用作于户外活动,之后在公元900年左右,一个单层的房间用石头和篱笆构筑了起来,这个房间很可能被用于居住,最后在公元900年后期或是公元1000年早期被废弃。 大约在公元1040年左右,在这个房间基址上新建了一面北墙和一个南北向的橱柜。 显然这个房屋被用于存放仪式物品,包括放置用于饮用巧克力饮品的圆筒罐。 持续的风沙抬高了相邻的庭院空间,所以在公元1070年左右,当房址28加盖了新的一层楼时,也一并修建了一条从下层房间通往庭院的楼梯。

大约在公元1100年左右,可能是仪式从业人员用砖石密封了房址28的西北门,他们把总计173个陶器放置于房址上层(其中包括112个圆筒罐置于房间的橱架上),而后封堵出口。这是美国西南地区考古史上在单一房址内发掘到保存完好的、数量最多的一批陶器。他们把绿松石和贝壳装饰品洒在陶器上,把燃料直接搁置在橱架下面,然后点燃燃料。显然他们从南门离开房间时,又一路撒上大量的饰物。这次大火非常剧烈,我们可以看到地面经高温已呈现玻璃化,最终房屋上层倒塌使得火势熄灭。这一系列的行为也能代表一种“终止仪式”:关闭房间以避免被进一步使用,并对仪式用品移除法力。很可能正因为人口数量的急剧减少的导致了一场“终止”行为。

我们的发掘还显示,房址28的回填显示两个不同的来源,一个严重烧毁的,而另一种是未燃烧的。我们认为这些回填的堆积来自于另外两个在房址28发掘之后的一年所发掘的相近的房址 。房址28a位于房址28东侧,其中一个房间也被烧毁,发掘采集了大约2000个木炭样品可能主要来自28a。在房址28号发现的未燃烧堆积来自北侧的房址53号,这个房址在1897年春天被沃伦·摩尔黑德野蛮地清理过,并将房址53的堆积扔至房址28。基于2013年房址28的室内整理工作,我们发现陶片能与房址53的拼对,因此我们作出这个推断。根据这三个单位出土遗物(在皮博迪博物馆、美国自然历史博物馆和查科文化国家公园博物馆展出)的仔细拼对,我们不仅证实房址28号的部分的回填物来自房址53,而且还发现并修复了至少12个先前未见形制的圆筒罐 。

通过对房址28号的发掘,我们还发现了大量动物遗存,包括可能用于制作扇翼的各类鸟翼骨;近五千件绿松石和贝壳饰物;在南墙石膏中有一个多脚指印;还有织物餐盘、花粉和大植物遗存。

从我们自己对房址28的发掘和对博物馆藏品的研究证实,大量圆筒罐曾储藏在该建筑中。现在已知大约200个查克文化圆筒罐中,有178个发现在普韦布洛博尼托遗址,除6个以外剩下都来自查克峡谷地区。事实上,只有两个圆筒罐出土于与墓葬直接相关的单位,剩下都发现于储藏室,但这些储藏室并非是与个人使用相关,出土背景分析显示这些圆筒罐应该是被某些团体控制。外来的可可豆的获取和饮用为查克社会的等级分化提供了机会。特别是那些在饮用饮品的仪式中担任重要角色的群体,在分享饮品的过程中产生了一种社会义务。普韦布洛博尼托遗址集中圆筒罐的发现和强化地饮用活动与建筑施工高峰期的时间相一致,暗示饮品可能可以用于交换了劳动力。房址28的烧毁和房内圆筒罐的“终止”仪式发生在这段密集施工期的结束之时,也是在美国西南的北部圆筒罐的停止生产和使用的时间。

我们正在进行的工作包括在普韦布洛博尼托遗址西部的发掘。 根据遗址公园的要求,我们希望能对整个遗址的利用情况提供准确的历史地图。我们也发现了先前未知的前西班牙殖民时期的特征,很可能包括一个水库。此外,威尔斯主导的一个大型国家科学基金会资助的项目正在研究整个峡谷的地下系统和农业特征,以期了解洪水如何影响我们对查科峡谷地区人类活动的认识。

我们长期的野外工作采用了多种手段:探地雷达以探测地下遗存,使用激光雷达系统(LiDAR)和全景拍摄系统(Gigapan)进行记录和地图的绘制;扫描电子显微镜和电子探针分析陶器和石膏的组成;稳定同位素分析动物遗存以了解它们是否在本地喂养;加速质谱仪和树轮测年;高效液相色谱质谱法检测有机残留物;并对所有文物、花粉、动物、大植物遗存和蜗牛进行整理研究。我们的项目表明,对遗址的再发掘可以提供全新的材料,不仅通过使用现代科技技术记录出土信息和分析材料,还凝聚原住民后裔、专业学者和跨学科专家的多方面力量共同检视新发现。

Pueblo Bonito is a large masonry town, or pueblo, located in Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico at an elevation of around 1890m. The site is part of the Chaco Culture National Historical Park, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, based on a concentration of over 4000 sites spanning the time period from Paleo-Indian to historic Navajo, and particularly those that form the core of what is called the Chaco Phenomenon: multi-storied masonry pueblos with adjacent roads that were part of an elaborate cultural system spanning much of the Four Corners area of the U.S. Southwest between about A.D. 950 and 1140.

Pueblo Bonito is among the largest and most completely excavated sites in the U.S. Southwest, encompassing around 600 masonry rooms up to four stories in height, as well as around 37 semi-subterranean masonry-lined structures called kivas and used primarily for ritual activities. Two major projects excavated most of Pueblo Bonito. From 1896-1899, the Hyde Exploring Expedition (HEE) excavated around 200 rooms under the supervision of Richard Wetherill and George Pepper. The National Geographic Society (NGS) sponsored an excavation of much of the remainder of the site under the supervision of Neil Judd between 1921 and 1927. Although most of the site was excavated by 1927, questions remain concerning the construction sequence of the site, whether water control was necessary for supporting such large sites in this inhospitable environment, the scale of interaction with surrounding and distant population, and the nature of leadership within the pueblo.

In 2004, we began a series of projects that address research questions by reopening parts of Pueblo Bonito previously excavated by the HEE or NGS projects. All of these projects involved consultation with the Native American tribes who are the descendants of the inhabitants of Chaco. All of the projects also involved undergraduate and graduate students (including many Native American students), as well as technical specialists. With funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and NGS, Wills reopened portions of three trenches originally excavated by the NGS through and between the two trash mounds south of Pueblo Bonito between 2004 and 2007. Our goal was to relocate deeply buried channels noted under the mounds to understand the relationship of water control systems to the development of Pueblo Bonito during the A.D. 1000s. The project aimed to answer this by recording the stratigraphy and taking radiocarbon and environmental samples. This project revealed that the residents of Pueblo Bonito constructed a large diversion channel just south of the town during the 11th century A.D. Sediments in the channel reflect repeated episodes of flooding, suggesting that it was built primarily to divert floodwaters away from the habitation site while providing water for construction and domestic use. It was destroyed by the late A.D. 1000s.

Within a few hours of reopening the trenches, we realized the NGS crews had pushed most of the artifacts from their excavations back into the trenches, and that we were now responsible for over 200,000 objects. With additional funding from NSF, Crown hired twelve graduate and undergraduate students to analyze this material between 2007 and 2009. The results of the project were recently published in The Pueblo Bonito Mounds of Chaco Canyon, edited by Crown. Among the ceramics were five that appeared to be of a rare form found primarily at Pueblo Bonito that archaeologists call cylinder jars. These tall, straight-sided jars sometimes have black designs on the white background and sometimes are all white or red. Crown was curious whether these might have been used as the Maya used this form, to drink chocolate, so she and collaborator W. Jeffrey Hurst performed High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry on the five sherds from the trash mounds, finding chocolate residues in three of them. This discovery demonstrated long-distance exchange of cacao from the sub-tropics of Mesoamerica to the American Southwest. The residents of Pueblo Bonito acquired not only cacao from Mesoamerica, but also scarlet macaws, copper, pseudo-cloisonné, and other exotic bird species and feathers from the south. What did they give in return? We do not know, but several scholars have suggested that turquoise ornaments were exchanged for Mesoamerican exotics.

The discovery of chocolate residues led Crown to request permission to reopen Room 28 in Pueblo Bonito, where 112 of the roughly 200 known cylinder jars were found in 1896. Prior to excavating, Ground Penetrating Radar verified that the deposits were intact and that charred posts remained in place on the lower floor. With funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and NGS and a crew of six graduate and undergraduate students, we re-excavated the room over a six-week period in 2013. We set out to determine how and when the room burned, whether the cylinder jars were on the lower or upper story, and whether the HEE excavators reached the original floor. The park also gave us permission to excavate below the levels reached by the HEE project to determine the entire sequence of use of this part of Pueblo Bonito.

We learned that early inhabitants of adjacent rooms had originally used the space as an outdoor activity area. Then around A.D. 900, a single-story room was constructed of masonry fronted with wattle and daub. It was likely used for habitation, and may have been abandoned in the late 900s to early 1000s. Around A.D. 1040, a new north wall was constructed in the room and a room-wide shelf built running north-south. The room was then apparently used primarily for storage of ritual objects, including the cylinder jars used for drinking chocolate elixirs. Accumulations of wind-blown sand had raised the adjacent courtyard area, so when an upper story was added to Room 28 around A.D. 1070, a stairway was constructed leading from the lower story room up to the courtyard level.

Around AD 1100, individuals who were probably ritual specialists sealed the northwest door of Room 28 with masonry. They placed 173 ceramic vessels, including 112 cylinder jars, on the room shelving, in groups blocking the doors, and on the upper room floor; this constitutes the largest group of whole vessels recovered from any single room in the U.S. Southwest. They sprinkled turquoise and shell ornaments over the vessels, and laid fuel directly beneath the shelving that held most of the vessels. They lit the fuel on fire and apparently sealed the south door to the plaza as they exited the room, placing quantities of additional ornaments in the stairway. The fire burned so hot it vitrified the sand floor, raging until the upper room collapsed and smothered the fire. This set of actions was likely part of a termination or retirement ritual, closing the room from further use and removing the power from objects viewed as animated. It is possible that another depopulation prompted this termination at Pueblo Bonito.

Our excavations also showed that the backfill in Room 28 came from two different sources, one heavily burned and the other unburned. We believe the backfill came from two nearby rooms excavated the year after Room 28 was excavated. One was Room 28a directly to the east of Room 28, and a room that also burned. Close to 2000 charred wood samples were collected during our excavations, probably primarily from this room. The unburned matrix found in Room 28 came from Room 53 to the north; this room had been plundered in the Spring of 1897 by Warren Moorehead and eventually the fill from his excavations was thrown into Room 28. We know this because portions of vessels found in his excavations and later clean-up work by the HEE fit sherds we recovered from Room 28 in 2013. Through careful matching of sherds from three repositories (the Robert S. Peabody Museum, the American Museum of Natural History, and the National Park Service Chaco Culture Museum, where our excavated materials are curated), we not only confirmed that the backfill in Room 28 came from Room 53, but also that Moorehead shoveled through portions of many additional vessels, including at least 12 previously unknown cylinder jars, scattering portions of them in a wide circle of rooms adjacent to Room 53.

The Room 28 excavations produced other remarkable finds: quantities of fauna, including a particularly high number and variety of bird wing bones probably originally deposited as wing fans; almost 5000 turquoise and shell ornaments; a polydactylous foot impression in the plaster of the south wall; as well as textile fragments, pollen, and macrobotanical remains.

Study of the materials from Room 28 from our own excavations and from museum collections confirms the high number of cylinder jars that were stored in that room. Out of approximately 200 known Chacoan cylinder jars, 178 were recovered in Pueblo Bonito, and all but six are from Chaco Canyon sites. The fact that only two of the vessels have been found in direct associated with burials and that most were found in storage rooms rather than domestic contexts indicates that they were owned by corporate groups rather than individuals or households. Acquisition of cacao and serving of exotic drinks in this special vessel form provided opportunities for differentiation in Chaco society particularly for the group that enacted the ritual in which the drinks were consumed. Sharing the drinks also generated social obligations among the participants in such gatherings. The concentration of cylinder jars at Pueblo Bonito signals and intensification of drinking activity that coincided with a period when construction events were at their height, suggesting that drinks might have been exchanged for work. The later burning of Room 28 and termination of the cylinder jars stored inside occurred at the end of this period of intensive construction and also the end to the production and use of cylinder jars in the northern Southwest generally.

On-going work includes excavations immediately west of Pueblo Bonito where the Wetherill family had their homestead and trading post. Conducted at the request of the park, this work provides accurate maps of the historical occupation. It also has exposed some previously unknown prehispanic features, including a possible reservoir west of Pueblo Bonito. In addition, a large NSF-funded project to Wills is examining deeply buried structures and agricultural features throughout the canyon to investigate how flood deposits have influenced our views of the history of occupation in Chaco.

Our long-term field work has employed a variety of methods: ground-penetrating radar to define buried deposits, LiDAR and Gigapan to record and map; Scanning Electron Microscopy and electron microprobe to determine the composition of ceramics and plasters; stable isotope analysis of fauna to determine whether they were procured locally and whether they were being fed; AMS dating and dendrochronology; High Performance Liquid Chromatography/Mass spectrometry to examine organic residues; and standard analysis of all artifacts, pollen, fauna, macrobotanical remains, and snails. Ultimately, our projects demonstrate that re-excavation can provide new insights into sites, not only through the use of modern technology to record deposits and analyze materials, but also through viewing these finds with the help of descendant communities, professional colleagues, and interdisciplinary specialists.