伯利兹素那多尼基遗址A9古墓和第三,四号象形文字碑的发现及其政治意义

The Discovery and Political Significance of the A9 Tomb and Hieroglyphic Panels 3 and 4 at Xunantunich, Belize

吉米·奥 Jaime J. Awe

(美国北亚利桑那大学 Northern Arizona University)

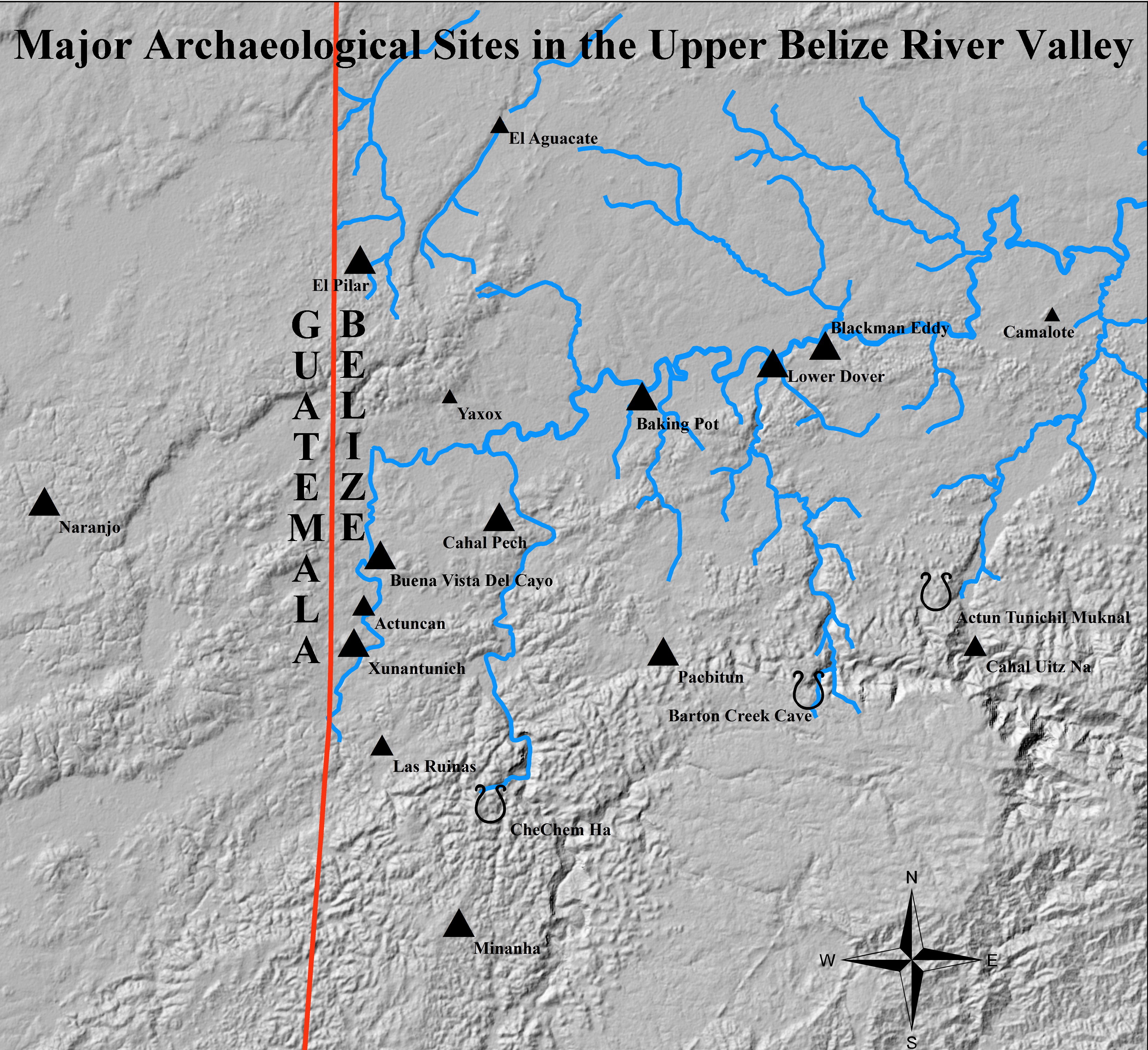

位于危地马拉边界的伯利兹河上游河谷涵盖了伯利兹这个国家最大的考古遗址群。其中之一的古城苏南图尼奇(Xunantunich)自19世纪以来只获得零星的考古关注。尽管有长期(但零星)的考古学关注,仅有很少数位于遗址中心区域的纪念性建筑曾经被系统调查过。为了填补这个缺漏并开发旅游业潜力,伯利兹政府在2000年至2004年期间于苏南图尼奇发起了一个为期四年的考古发掘与保护项目。吉米·奥领导这个项目并成功地发掘和保护了遗址核心区域的六栋主要建筑。这个项目还保护了位于卡斯蒂略(Castillo)大型宫殿建筑三座雕刻纪念碑残片中的一个脆弱的灰泥腰线(stucco frieze),并且发现了其中一座首批发现的贵族墓。由于这个为期四年的项目相当成功,吉米·奥于2015年返回这个遗址,开始了另一个长期的挖掘和保护项目,也就是苏南图尼奇考古与保护项目,该项目有两个主要目标:一是以进一步发展旅游为目的继续保护遗址中心的宏伟建筑。二则是取得更多资料来提供我们进一步理解苏南图尼奇于古典期晚期(Late Classic period ; 公元650-850年)在伯利兹河谷政治地景所扮演的角色。

在2015年的田野工作期间我们在遗址中心东部边缘区域发掘并保存了一座位于主要卫城的小神殿以及两座寺庙金字塔。2016年的发掘工作移至中庭的西侧,并开始对建筑A9进行调查。如同苏南图尼奇大部分的建筑一样,A9在过去仅受到了有限的考古学关注。A9的第一次发掘是在1890年末由英国医生同时也是一位考古爱好者,汤马斯·江恩(Thomas Gann),在土丘顶部发掘了一个大型的坑口。第二次的发掘工作则是在1990年代由加州大学洛杉矶分校进行,他们的工作集中在建筑物的南侧。第二次的发掘揭开了建筑物的地基台面,而第一次的发掘工作则在接近地表下方的建筑物的顶部发现了一个简单的墓葬。

我们2016年的调查工作集中于A9的东侧包含了两个大型发掘区。第一个发掘区包括了整个土丘东部的地基。第二个发掘区则包含了由从基地延伸到建筑物顶部的轴向沟槽。在在前三周的工作期间,我们的调查取得了一些重大发现,包含3号和4号象形文字碑版、A9-2墓葬,建筑中央楼梯的第一阶下方发现的两个藏物箱或陪葬箱,以及在建筑底部下方所发现的未雕刻石碑。

根据我们的翻译,4号碑上的象形文字提到这座纪念碑含有一个自18 K’ank’in这个日期开始的主要条文。有趣的是,这个日期相当于公元642年12月7日,同时也出现在危地马拉纳兰霍(Naranjo)遗址发现的一个象形文字的阶梯上。然而,更重要的是四号碑上的条文清晰地描述了古典时期强盛的蛇王朝从原来的权力中心(位于墨西哥今日的迪齐班切(Dzibanche))来到卡拉克穆尔(Calakmul)遗址的重建经过,这个过程以被证明是结束在9.10.10.0.0的lahuntun时期(公元642年12月7日)完成的

3号碑的铭文提供给我们三个事件。第一个是关于死于公元638年的巴茨艾克女士(Lady Batz’ Ek)的死亡事件。位于苏南图尼奇南边约50公里处的卡拉科尔(Caracol)遗址的铭文将巴茨艾克女士认定为君主卡恩二世(Lord Kan II)的母亲,卡恩是该地拥有皇族血统的显赫统治者。3号碑铭文的第二个事件提到Waxaklajuun Ubaah Kan死于公元640年,他是卡努尔王朝或蛇王朝的统治者。第三个陈述则提到了一场球赛。

储藏箱中包含了各种各样的本地和外来物品,其中包括36个黑曜石和燧石小雕像。 A9-2墓被封闭在一座大墓中,里头有一名身体健壮的成年男性的遗体,死亡年龄约为四十岁。陪葬物有32个陶器、玉器、贝壳首饰、几个黑曜石刀片、以及一箱猎豹骨和鹿骨。

在发现了苏南图尼奇铭文之前,关于蛇王朝从原来的位于迪齐班切的地方转移到卡拉克穆尔只是铭文学家猜测出来的,未曾发现具体的证据。然而我们发现的铭文明确指出这个权力转移其实是蛇王朝两派系之间“内战”的结果。由Waxaklajuun Ubaah Kan领导的迪齐班切派失去了这场战争,他被俘虏并被他在卡拉克穆尔的王朝亲属牺牲掉。

随着在卡拉克穆尔的权力地位建立,卡努尔或蛇王朝最终成为玛雅世界古典时期最强大的王国之一。自公元562年到公元7世纪末,蛇王王国建立了战略联盟,使他们能够击败征服在位于玛雅低地的主要区域竞争对手。这些成功也使他们得以从被打败的政体中徵集贡品,并将卡拉克穆尔建设成为玛雅世界上最大且最主要的城邦之一。

但是,这与苏南图尼奇又有什么关系呢?在发现苏南图尼奇的遗物不久之后,我们开始质疑象形文字碑的来源,因为这些铭文的风格和古文字都不像其他在苏南图尼奇发现的雕刻纪念碑。而用于生产面板的致密石灰石也是同样的情况。我们的地质学家证实用于制造3号和4号碑的原料更像典型的卡拉科尔(Caracol)石灰石;卡拉科尔是位于伯利兹玛雅山脉南部约50公里的大型城市中心。我们项目的铭文学家对铭文的分析也表明,这两个文字碑实际是属于纳兰霍发现的象形文字阶梯的一部分,纳兰霍是位于危地马拉西部14公里的另一个大型城市中心。

纳兰霍的象形文字阶梯最早在1905年由奥地利探险家提欧柏·梅勒(Teobert Maler)在纳兰霍的危地马拉遗址所记录下来。随后,铭文学家西尔韦纳斯·莫利(Sylvanus G. Morley)于1909年参观了这个地方,并记录了雕刻在楼梯上的日历信息。英国铭文学家伊恩·格雷厄姆(Ian Graham)在20世纪70年代对纳兰霍的另一次访问中,描绘并记录了雕刻在纪念碑上全部的象形文字资料。格雷厄姆对此象形文字楼梯的原始记录仍然是纳兰霍象形文字楼梯的主要信息来源,因为除了楼梯的一部分之外,其余的楼梯碎片随后都从遗址被盗并在古物市场出售。

琳达·谢尔(Linda Schele)随后在1980年对格雷厄姆的照片和绘画进行分析,得出了几个非常有趣的观察结果。研究显示,楼梯上的那些有铭文的区域或砌块是没有语法的,楼梯不但遗失了一些碎片,而且这些砌块是以一个难以辨认的顺序排列的。更有意思的是,尽管文字砌块的秩序是乱七八糟的,但铭文还是指出,这个台阶是由卡拉科尔的统治者,君主卡恩二世所委托制造并记录了他在公元631年击败纳兰霍。谢尔和大卫·弗道尔(David Freidel)都认为,君主卡恩二世是故意在被击败的敌人的首都建造了象形文字的楼梯,这显然是为了加深“侮辱失败者”。然而,这个结论困扰了后来的铭文学家,因为它不能解释楼梯的砌块被放置的语法和秩序。这种不一致最终导致了西蒙·马丁(Simon Martin)和尼古拉·格鲁比(Nikolai Grube)在2004年提出了另一种假设。马丁和格鲁比提出,象形文字的楼梯最初是在631年由卡恩二是在他的首都卡拉科尔建造的。49年后在公元680年,纳兰霍的K’ahk Chani Chan Chaahk攻击击败了卡拉科尔,为他的城市报了仇,然后拆除了大部分的象形文字阶梯碎片并运到纳兰霍。这些碎片随后被安装在纳兰霍被发现的建筑物上,但故意重新组装,使其无法辨认(或语法不清)。

当我们把所有这些看似矛盾的信息连在一起后,以下的情况就逐渐明朗了。很显然,卡恩二世在公元631年击败纳兰霍之后,他委托工匠在他的首都卡拉科尔雕刻和建造象形文字阶梯。4号碑上的日期指明阶梯是在公元642年完工并竖立起来。除了描述了他击败纳兰霍之外,还提到了卡恩二世的母亲巴斯克勒夫人的死亡,蛇王朝的Waxaklajuun Ubaah Kan之死,以及将蛇王朝权力中心移至卡拉克穆尔等事件。卡恩二世之所以在这个象形文字的台阶上提到这些事件,是因为他是蛇王朝的卡拉克穆尔分支的一个盟友,而且他的母亲很可能隶属于那个王朝,并以政治联姻的方式来到卡拉科尔。公元680年,在卡恩二世击败纳兰霍49年后,纳兰霍统治者向卡拉科尔报复。除了击败后者,纳兰霍统治者拆除了在卡拉科尔的象形文字的楼梯,然后将大部分的砌砖移到了纳兰霍,并重新组合使他们难以辨认。

虽然后者的信息确实使我们能够将解释3 号和4号碑的象形文字铭刻在苏南图尼奇被发现的背景,同时也帮助我们确定了这两座古迹的起源,但仍然无法回答两个主要问题:所谓纳兰霍象形文字阶梯的两个碎片是如何到达苏南图尼奇的?为什么它们被放置在建筑A9的侧面呢?一个可能但是假设性的答案是:埋葬在A9-2中的贵族与导致楼梯从原来在卡拉科尔的位置被拆除有关。位于纳兰霍和苏南图尼奇的铭文都表明,这两地在七世纪和八世纪是密切的盟友。因此我们假设,如果葬于A9的个体在公元680年参与了击败卡拉科尔的战役,并且这些碑可能是他在所分配到战利品。这也可以解释为什么这两个小组最终竖立在他的墓葬寺庙楼梯的两侧。为了验证这个假设,在公元680年纳兰霍和卡拉科尔战斗的期间,埋葬在A9-2中的个体必须是活著且为成人。为了检验这种可能性,我们将来自墓穴的人类和动物骨骼进行碳十四加速器定年分析。人类遗骸所测得的年代是公元660-775年,而鹿骨的年代是公元690-890年。虽然两者跨度的时间都是100年左右,但是这两个定年都证实了墓中的个体肯定活得足够老并可以参加纳兰霍和卡拉科尔之役。在墓中发现的两件陶器上所记录的结束日期也为这种可能性提供了进一步的确认:其中一件陶器的结束日期为10 Ajaw,或公元672年,另一件则为8 Ajaw或公元692年。同样的,这两个日期都与战役日期重叠,并为A9-2号墓中的个体可能作为纳兰霍盟友参加战役的假设提供了额外的支持。

在我们在苏南图尼奇进行调查之前,过去的研究人员已经注意到这个遗址直到七、八世纪才出现。他们推测苏南图尼奇能在这个时代在这个区域快速增长,是与政治组织从一个自治中心转移向一个隶属于纳兰霍的政体相关。他们还建议,苏南图尼奇可能是一个依赖纳兰霍的盟友,也可能是一个被直纳兰霍直接统治的省;而这位统治者可能是当地贵族成员,也可能是来自外地而被指派到这个新的权力中心。为了确定A9-2墓中的个体是本地的还是外地的,我们决定对人类遗骸进行锶同位素分析。过去的研究表明,伯利兹河流域的锶平均值约为0.7086,范围为0.7082〜0.709。而A9墓中个体的分析结果的结果为0.708386。这个锶值非常符合伯利兹河流域的背景质,暗示埋在墓中的贵族是本地人,而不是从纳兰霍安插入到苏南图尼奇政治地景的外来者。

我们在苏南图尼奇的调查体现了运用多学科的科学分析对考古学研究的价值。它进一步证明了精细挖掘技术的价值、古人类遗骸中锶同位素分析的应用、动物遗骸的动物考古学分析、墓葬陪葬器物的分析,人类和其他有机遗体的放射性测年,以及古代玛雅象形文字的破译。只有采用这种整体的方法,我们现在才能开始解开过去的许多秘密,同时也有助于伯利兹国家考古资源的发展。

The upper Belize River Valley, which is located along the border with Guatemala, contains some of the largest archaeological sites in the country of Belize. One of these ancient cities, known as Xunantunich, has been the focus of sporadic archaeological attention since the late 19th century. In spite of this long history of archaeological attention, however, few of the monumental buildings in the site’s epicentre had ever been systematically investigated. In an effort to address this omission, and to develop the site for its tourism potential, the Belize Government initiated a four-year program of excavation and conservation at Xunantunich between 2000 and 2004. The project, which was directed by Jaime Awe, successfully excavated and conserved six of the major structures in the site core. It also conserved a fragile stucco frieze on the large palace complex known as the Castillo, located fragments of three carved monuments, and discovered one of the first elite tombs at the site. Because of the success of the four-year project, Awe returned to the site in 2015 to begin another multi-year program of excavation and conservation. Known as the Xunantunich Archaeology and Conservation Project, this second project has two major goals. The first goal is to continue conserving the monumental architecture of the center in an effort to further develop the site for tourism purposes. The second goal is to acquire data that will further our understanding of the role of Xunantunich in the political landscape of the Late Classic period (650 – 850 A.D.) Belize River Valley.

During the 2015 field seasons, the project excavated and conserved a small shrine on the main acropolis and two temple pyramids on the eastern border of the site core. In 2016, excavations moved to the west side of the central courtyard, and began investigations on Structure A9. Like most of the buildings at Xunantunich, Structure A9 had received limited archaeological attention in the past. The first excavation on A9 was that conducted by British medical doctor and archaeological enthusiast Thomas Gann, who excavated a large crater at the summit of the mound in the late 1890s. A second excavation, by a UCLA project in the 1990s, focused on the south flank of the building. The latter excavation uncovered the basal terrace of the structure while the former discovered a simple burial just below surface at the summit of the building.

Our 2016 investigations focused on the eastern flank of Structure A9 and consisted of two large excavation units. The first excavation encompassed the entire eastern base of the mound. The second unit consisted of an axial trench that extended from the base to the summit of the building. Within the first three weeks of operation, our investigations made several significant discoveries. The finds included Hieroglyphic Panels 3 and 4, Burial A9-2, plus two caches or offerings that were discovered below the first step of the building’s central stairway, and below the base of an uncarved stela.

The caches contained a variety of local and exotic objects, including 36 obsidian and chert eccentrics. Burial A9-2 was enclosed in a large tomb, and contained the remains of a robust adult male who was about 40 years at the time of death. The burial was accompanied by 32 ceramic vessels, jade and shell jewellery, several obsidian blades, and a cache of jaguar and deer bones.

Our translation of the hieroglyphic inscriptions on Panel 4 noted that this monument contained a single major clause that started with the date 18 K’ank’in. Interestingly, this date, which corresponds to December 7 in AD 642, also occurs on a panel from a hieroglyphic stair that was discovered at the site of Naranjo in Guatemala. More significantly, however, the clause on our Panel 4 provides an articulate description of the dynastic re-establishment of the powerful Classic Period Snake-head dynasty from its original seat of power (at Dzibanche in present day Mexico) to the site of Calakmul, a process that was evidently thought to be completed by the lahuntun Period Ending of 9.10.10.0.0. (December 7, ad 642).

The inscriptions on Panel 3 provided us with three statements. The first was a death statement for Lady Batz’ Ek who died in 638 AD. Inscriptions at the site of Caracol, located about 50 kilometers south of Xunantunich, identify Lady Batz’ Ek as the mother of Lord Kan II, a prominent ruler of that site’s royal lineage. The second statement on Panel 3 includes another death statement for Waxaklajuun Ubaah Kan, a ruler of the Kaanul or Snake Dynasty who died in 640 AD. The third statement referred to a ball game.

Prior to the discovery of the Xunantunich panels, the transfer of the Snake Dynasty from its original seat of power at Dzibanche to Calakmul had only been conjectured by epigraphers. Concrete proof for this change, however, had previously never been recovered. Our panels also made it clear that the transfer of power from one polity to the other was the result of a “civil war” between two factions of the Snake Dynasty. The Dzibanche faction under the leadership of Waxaklajuun Ubaah Kan lost that war, he was taken captive, and subsequently sacrificed by his dynastic relative at Calakmul.

With the establishment of its seat of power at the city of Calakmul, the Kaanul or Snake Dynasty eventually became one of the most powerful kingdoms of the Classic period Maya world. From about 562 AD, to almost the end of the 7th century, the kings of the Snake Dynasty established strategic alliances that enabled them to defeat and subjugate their major regional competitors in the Maya lowlands. These successes also allowed them to exact tribute from the defeated polities, and to establish Calakmul as one of the largest and most dominant city states in the Maya world.

But what does all this have to do with Xunantunich? Shortly after their discovery, we had begun to question the origin of the hieroglyphic panels because neither the style of execution or the palaeography of the inscriptions were similar to the style rendered on other carved monuments at Xunantunich. The same was true of the dense limestone used to produce the panels. As our geologist confirmed, the raw material used for the production of Panels 3 and 4 was more typical of the limestone used to produce the carved monuments at Caracol, a large center about 50 kilometres due south in the Maya Mountains of Belize. Analysis of the inscriptions by our project epigrapher also indicated that the two panels were actually part of a hieroglyphic stairway that had been discovered at Naranjo, another large center located 14 kilometres to the west in Guatemala.

The Naranjo hieroglyphic stair was first documented at the Guatemalan site of Naranjo by Austrian explorer Teobert Maler in 1905. In a subsequent visit to the site in 1909, epigrapher Sylvanus G. Morley recorded the calendrical information carved on the stair. In yet another visit to Naranjo in the 1970s, British epigrapher Ian Graham illustrated and recorded the entire hieroglyphic data carved on the monuments. Graham’s in situ documentation of the hieroglyphic stair remains the primary source of information on the Naranjo Hieroglyphic Stair because all but one fragment of the stair was subsequently looted from the site and sold in the antiquities market.

A subsequent (1980s) analyses of Graham’s photographs and drawings by Linda Schele resulted with several very interesting observations. The study revealed that the inscribed sections, or blocks, of the stair were out of syntax, that the stair was missing some fragments, and that the blocks had been set in an illegible order. Even more interesting was that, in spite of the scrambled order of the glyph blocks, the inscriptions indicated that the stair had been commissioned by Lord Kan II, ruler of Caracol, to record his defeat of Naranjo in 631 AD. Schele and David Freidel also argued that Lord Kan II purposely erected the hieroglyphic stair in the capital of his defeated enemy in an apparent effort to add “insult to injury.” This conclusion, however, bothered later epigraphers for it failed to explain why the inscribed blocks of the stair were placed out of syntax and order. This inconsistency eventually led Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube to offer an alternative hypothesis in 2004. Martin and Grube proposed that the hieroglyphic stair was originally erected by Kan II at his own capital of Caracol in 631 AD. Forty-nine years later, in 680 AD, K’ahk’ Xiiw Chan Chaahk of Naranjo avenged his city by attacking and defeating Caracol, and then dismantled and transported most of the fragments of the hieroglyphic stair to his Naranjo. These fragments were subsequently mounted on the building where they were discovered at Naranjo, but purposely reassembled out of order to make them illegible (or out of syntax).

When we put all these seemingly, disjointed pieces of information together in a cohesive manner, the following picture began to emerge. It was apparent that following his defeat of Naranjo in 631 AD, Lord Kan II commissioned the carving and construction of a hieroglyphic stair that was erected at his capital city of Caracol. The date on Panel 4 indicates that the stair was completed and erected in 642 AD. Besides describing his defeat of Naranjo, inscriptions on the stair blocks also mentioned the death of Lord Kan’s mother Lady Batz’ Ek’, the death of Waxaklajuun Ubaah Kan of the Snake Dynasty, and the transferal of the Snake Dynasty’s seat of power to Calakmul. The reason why Kan II makes reference to these events on the hieroglyphic stair was because he was an ally of the Calakmul’s branch of the Snake Dynasty, and because his mother was likely affiliated with that dynasty, coming to Caracol as part of a marriage alliance. In 680 AD, 49 years after their defeat by Kan II, the ruler of Naranjo exacted revenge on Caracol. Besides defeating the latter, the Naranjo ruler dismantled the hieroglyphic stair at Caracol, then moved most of the blocks to Naranjo where they were reassembled out of order so as to make them illegible.

While the latter information certainly allowed us to contextualize the hieroglyphic inscriptions of Panels 3 and 4 at Xunantunich, and while it also helped us to determine the origins of the two monuments, two major questions still remained unanswered. That is, how did two fragments of the so-called Naranjo Hieroglyphic Stair make their way to Xunantunich, and why were they placed on the flanks of Structure A9? One potential, but hypothetical, answer was that the elite interred in Burial A9-2 was somehow associated with the events that resulted in the dismantling and removal of the stairs from its original location at Caracol. Inscriptions at both Naranjo and Xunantunich indicated that the two sites were close allies during the 7th and 8th centuries. We therefore hypothesized that if the individual in Burial A9 participated in the defeat of Caracol in 680 AD, that the panels were likely his share of the war booty. This could also explain why the two panels were eventually erected on the flanks of the stairway of his funerary temple. To validate this hypothesis, however, the individual in Burial A9-2 would have had to be alive and of mature age during the battle between Naranjo and Caracol in 680 AD. In an effort to test this possibility, we submitted fragments of human and animal bone from the tomb for AMS 14C dating. The date on the human remains came back at 660 – 775 calibrated AD, and the date on the deer bone was 690 – 890 AD. Although both had a spread of about 100 years, both dates nevertheless confirmed that the individual in the tomb could have certainly been alive and old enough to participate in the battle between Naranjo and Caracol. Period ending dates on two ceramic vessels found in the tomb provided additional confirmation for this possibility. One of the tomb vessels had a period ending date of 10 Ajaw or 672 AD, and the other had a date of 8 Ajaw or 692 AD. Again, both of these dates overlap with the date of the war event, and provide additional support for the hypothesis that the individual in Tomb A9-2 likely participated in the war as an ally of Naranjo.

Prior to our investigations at Xunantunich, previous researchers at the site had noted that the site did not rise to prominence until sometime around the 7th to 8th centuries. They surmised that Xunantunich’s rapid growth around this time corresponded with a shift in the polity’s political organization, from an autonomous political center to a polity subordinate to Naranjo. The also suggested that Xunantunich was either a dependent ally or a directly ruled, annexed province of Naranjo, and that the site’s rulers could have either been members of a local elite family elevated to this new position of authority, or they could have been outsiders inserted into the valley’s political landscape. To determine whether the individual in Tomb A9-2 was local or foreign, we decided to conduct strontium isotope analysis on the human remains. Previous research in the region had established that the mean strontium values for Belize River Valley sites was about 0.7086 with a range of 0.7082 to 0.709. Results of our analysis on the Structure A9 individual yielded a value of 0.708386. This strontium value fits the Belize River Valley signatures very well, suggesting that the elite buried in the tomb was local, and thus not inserted into the Xunantunich political landscape by Naranjo.

In conclusion, our investigations at Xunantunich exemplifies the value of applying multi-disciplinary scientific analysis to the study of the archaeological record. It further demonstrates the value of conducting meticulous excavation techniques, the application of strontium isotope analysis on ancient human remains, zooarchaeological analysis of animal remains, artifact analysis of grave goods, radiometric dating of human and other organic remains, and the decipherment of ancient Maya hieroglyphic writing. It is only through the application of this type of holistic approach that we can now begin to unravel many of the secrets of the past, while at the same time contributing to the development of the archaeological resources of the country of Belize.