多瑙河下游皮尔曲勒红铜时代的莫谷拉戈加纳土丘遗址

The Copper Age Settlement Mound 'Măgura Gorgana' near Pietrele on the Lower Danube

斯文德·汉森 Svend Hansen

(德国考古研究所 German Archaeological Institute)

罗马尼亚南部皮特雷勒附近的莫古拉·戈加纳土丘是一处略呈椭圆形的聚落遗址,周长约255米,东西近97米,南北90米,最后阶段的遗存仍高达11.5米,比周围高出9米,令人印象深刻。在该聚落被放弃之前,壮丽的山丘耸立在多瑙河河谷之上,从远处就能看到。

自2004年以来的每个夏天,由德国研究基金会的慷慨资助,德国考古研究院欧亚部、罗马尼亚科学院考古研究所与法兰克福歌德大学自然地理研究所合作在多瑙河下游的皮特雷勒遗址开展考古发掘。

据目前研究,该土丘聚落起止于约公元前4550-4250,延续了约300年。同期的东南欧多数地区的土丘聚落早已被放弃了。罗马尼亚南部的土丘不仅与此类型聚落的晚期改变不同,与东南欧其它土丘聚落在形式上也不同。表现之一在于它们的高度与陡坡,使得这些聚落普遍高于周围的环境,与喀尔巴阡盆地南部希斯–温查文化的平地聚落完全不同。

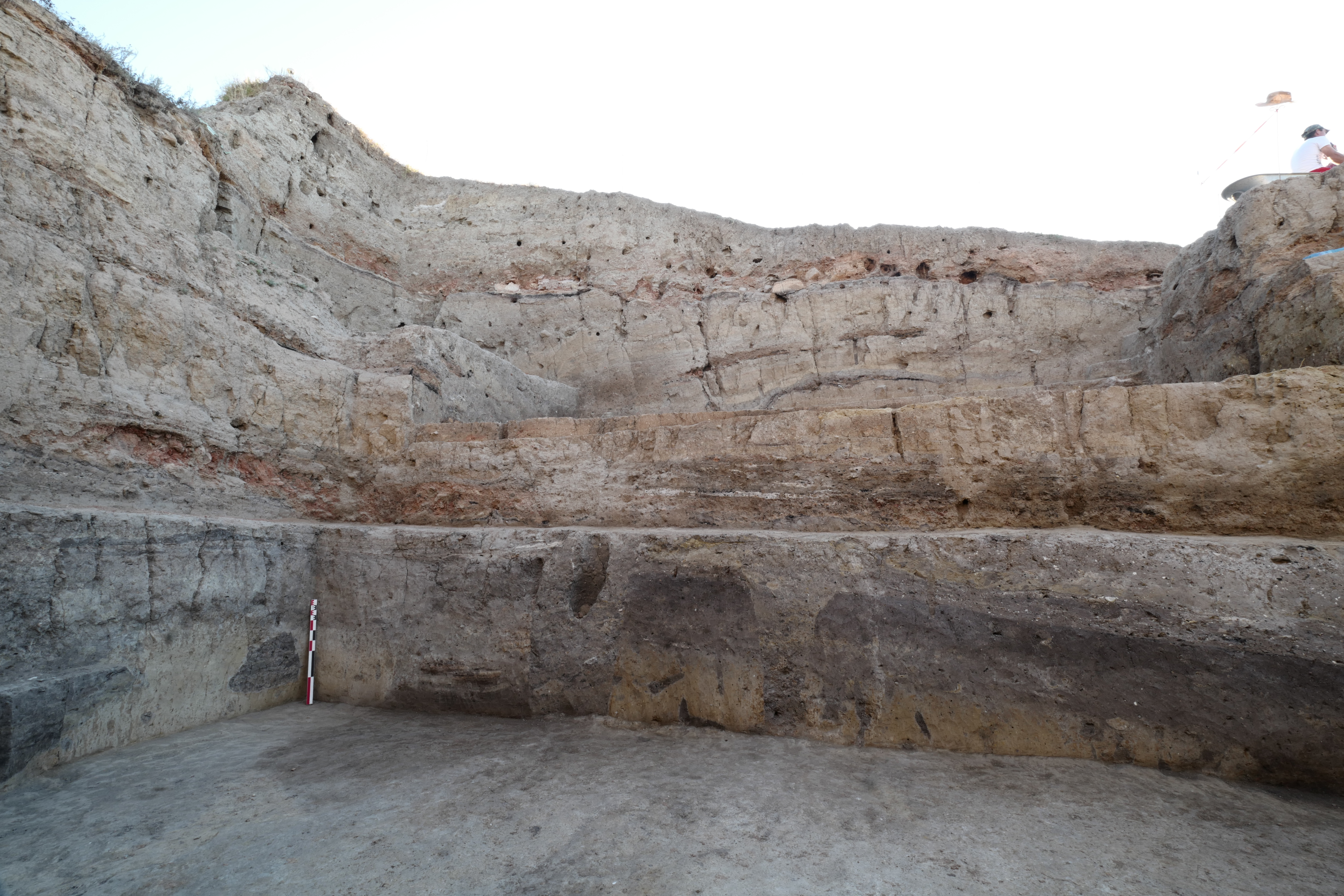

我们在土丘南部发掘出一个完整的聚落序列,提供了厚达11.5米清晰的层位关系,这是难得的成果,既需要高超的技术又耗费时间。这项成果是第一次完整的、有记录的揭示出延续了300年的古梅尔尼亚文化(公元前4550-4250年)的地层关系。

300多年累积11.5米的厚度非常罕见;相较之下,著名的保加利亚色雷斯卡拉诺沃土丘聚落堆积达13米高,面积比皮特雷勒遗址稍大,但从新石器时代早期一直延续到青铜时代。其中的第六层,与皮特雷勒遗址同期,厚度也就在3米多。

一个时段内皮特雷勒遗址堆积厚达11米多的地层该如何解释?也许,我们不能认为这是聚落残留下来,而应引入土丘是仪式性建筑的想法。 整个土丘上遍布着被烧过的或毁坏过的房子,一层摞着一层,垫土就来自于土丘周边。放射性碳年代测定清晰的表明,该遗址的使用从来没有中断过,也没有被扰乱过。另外,该遗址出土了2500余件完整器物,这极利于了解陶器的发展,而这些房址就可以用作“封闭情境”,这也将是研究陶器的基础。

所有烧过的没烧过的房子都被厚约1米的黏土和沙包覆盖着,之后新房子会在这层垫土上起建,因此土丘聚落堆积快速。大量的沙包不仅能封锁住原来的地层,同时也为新房子的起建提供必要的地基支撑,而新房子的柱洞就挖在这些填土里。显而易见,生活在土丘上似乎特别有意思。在这里生活,不仅充满了攀爬的起起伏伏,而且在整个使用期间,来自大火及随之而来的破坏、土丘自身的滑坡与空穴等威胁与日俱增。

长期以来,人们认为土丘聚落是一个完整的聚落。而我们研究的最重要的成果之一是在土丘底部发现了一个相当大的聚落,占地约5公顷的平地聚落,地球物理调查尚未找到四至。由于整个平地聚落是在土丘聚落使用后期出现的,那么问题就来了,该如何阐释土丘自身呢?一种意见认为,土丘聚落既是整个聚落的核心,又是社会与政治统治的代表。最有力的证据是数量多且普遍质量高的文物,如金属制品。

该遗址起始于约公元前4550年,或据罗马尼亚考古学术语,新石器时代晚期(博扬文化)与铜器时代(古梅尔尼亚文化)之间的过渡期。该地区其它遗址的几个碳十四年代提供了可供对比的数据,加剧了这一时期的复杂性。因此,这个土丘聚落成了一个庞大的新建计划的组成部分,我们也可据此认为皮特雷勒是新式建筑而非之前新石器时代的。

地形

从一开始,重建公元前5000年的地貌对发掘皮特雷勒至关重要。研究结果表明,在这一时期,多瑙河流经一个大湖,暂时命名为“拉库尔 · 戈加纳”。该湖大致范围在如今的朱尔朱到奥尔特尼亚,可能比博登湖大。这些结果的意义并不局限于皮特雷勒当地的定居历史,而且还远远超出了这一范围。新石器时代和铜器时代的定居点坐落在现今草甸的台地边缘,这里曾经是古奥莱克的河堤。皮特雷勒,与其它铜器时代的聚落一起,可以直接从大湖和多瑙河里取水。诸如萨尔塔娜等土丘聚落,如今似乎坐落在内陆地区,但它们很可能与湖泊系统相连。

毫无疑问,这些湖畔居民为了出行方便都配备了船只。遗址出土的大量鱼类遗存可以看出,湖泊不仅为皮特雷勒居民提供了重要的食物资源,而且也是重要的交通系统。此外,湖边遍布着古梅尔尼亚时期的遗存,这些湖畔定居点基本上构成了该文化的核心,该文化与色雷斯卡拉诺沃文化及保加利亚科多阿德门文化多有不同。

如上所述,湖泊为皮特雷勒居民及周边聚落提供了丰富的食物资源。良好的保存状况、大量可复原的骨头的采集以及湿筛法的采用为研究皮特雷勒遗址大规模捕鱼活动提供了方法上的可靠基础。多数鱼类遗存为鲤鱼科、鲇鱼、鲈鱼和梭鱼。不过,只有很小一部分的捕鱼工具和材料被保存下来,渔网、渔栅或木制渔具本来可以保存在被水浸过的定居点,但它们早就变质了。但渔网捕鱼一定是最常使用的,这体现在大量的小鱼残骸上。

社会考古

东南欧的铜器时代在整个欧洲文化发展史上是一个动荡期。采矿和冶炼新金属材料的战利品不仅使它们自己被命名为一个新的考古时代,而且毫无疑问它们还带来了自农业出现以来最具革命性变化的冲击。无论是现代工业还是由此产生的技术发展,都离不开金属。直接后果可能只局限在区域范围内,但它们最终是如此普遍,以至于很快导致了许多领域内不可逆转的发展态势。铜和金对喀尔巴阡盆地和东南欧的发展带来了特别深刻的影响。

金属所提供的潜力的大小当然不是完全可以估量的,但是这种材料的特性无疑在概念上提出了重大的观念障碍:一种材料能表现出如此不同的性质,而且易于以多种方式操作,能够完美地再现任何物体,这在以前是闻所未闻的。的确,金属作为一种材料,实际上是取之不尽用之不竭的:一旦开采出来,就形成了生产、使用和冶炼的连续循环。随着冶金学的兴起,不仅出现了技术革新,而且出现了社会变革的过程。

陪葬品的发现,特别是那些来自瓦尔纳墓地的,在代表死者所拥有的社会等级的陪葬品财富方面显示出明显的梯度。发掘莫古拉·戈戛纳的最初目的是研究瓦尔纳墓地的社会–历史分层,因为具有象征意义的随葬品的发展是定居社会经济发展的一面镜子。

人工制品在皮特雷勒房屋之间的分配,对支持包括专业化和劳动分工在内的经济差异活动的论点起了决定性的作用。物质文化的普遍一致性需要一个复杂的系统,不仅是在交换过程方面,而且在生产技术方面,其专门化远远超出单个聚落的范围。

在皮特雷勒,可以确定人工制品分配上存在相对明显的差别:比如,南部的探沟F中的房址内出土了绝大部分的狩猎捕鱼制品。类似的,北部探沟B内的3处房基内出土了谷物碾磨和纺织产品,现场发现了未被扰动且未烧毁的织机2架。我们倾向于认为这里存在着不同经济专长的家户。也许这些生产活动并不只是在家户中进行,但从遗址整体来看,土丘上并不存在同质的经济活动。

摆在眼前的专业化表明新的职业被唤醒了,并从中产生了传统:如陶工、长刀制造者和铸工。事实上,专业人员确实存在于公元前5千年,这绝不是考古学理论上的虚构。

探沟F内无打破关系的8座房子持续不断的延续了300年,家族内代代相传,为狩猎和捕鱼专业化提供了有力证据。由此可以推测,孩子继承并学习父母的职业是一种家庭传统。建立劳动分工的另一种方法就是了解产品的制造。我们可以从新石器时代已经建立的极其复杂的手工知识中得出结论,即在维持生计的部门之外存在着一种协作生产过程,这种手工知识一定是代代相传的。

金属制品的生产同样需要专业知识。该遗址出土约300件铜制品主要是铜锥、铜针和一把铜凿, 很可能不是本地生产,而是来自于尚未确认的外部作坊。另一方面,确认欧洲最古老的铅矿开采就在皮特雷勒。利用便携式X射线荧光和一系列实验室分析,在从遗址采集的11个双锥形容器(坩埚)中发现了微量的铅。这种熔炼过程的最终产品仍不清楚,但它似乎与金属生产过程没有直接关系。然而,该遗址出土的大量同类器物以及罗马尼亚和保加利亚其它同时期的聚落和墓葬表明,此类活动是一种广泛的文化实践,我们可以相当准确地确定年代在公元前4400-4300年之间。

到目前为止,该遗址已经发现了大约1.3万块燧石刀片和石叶残片,这些刀片和石叶残片仅作为成品运抵该聚落。20多公分长的石叶(所谓的“超级石叶”)明显是专业工匠的产品。另外,实验考古调查表明,制作如此高质量的石片需要大量的练习。“超级石叶”是采用“压杆”技术制作的,在瓦尔纳和杜兰库拉克的墓葬内以及土丘聚落内均出土了大量的此类遗存,皮特雷勒遗址也是如此。如上所述,这些石叶需要专业知识才能制作,这一过程很可能是在保加利亚东北部燧石矿里的作坊里进行的。

甚至连陶器都是由专门的陶工制造的,部分证据是用进口石墨装饰的大碗,碗上的图案复杂而迷人,这几乎肯定需要大量的知识、实践和技能才能完成。

在专业化生产的陶器组合中有大口陶坛(pithoi),是一种大型储存容器,在该遗址中被视为技艺精湛的高端产品。这些陶器的发现表明,陶工不仅掌握了生产此类尺寸容器的技术上和时间上的要求,而且具备了控火能力,这些知识对于此类器物的生产绝对是至关重要的。相较于小型实用陶器,制作大型陶器需要更加复杂的技术。

因此,我们对大型储存陶器的工艺史特别感兴趣。此类器物上的纹饰也为小型陶器所不见。这是大口陶坛(pithoi)上典型的纹饰,因为螺旋形图案没有可见的起点或终点,因此会给观察者带来特殊的不确定性。

皮特雷勒出土的大口陶坛(pithoi)暗示着专门化的工艺以及生产的过剩。这些陶罐的容量多达400升,从根本上证明了剩余产品最有效的储存方法。同样,这种特殊产品的工艺专门化是由于需求的增加而产生的,只有在需求持续走高的情况下才能维持。因此,关于超大陶罐生产的专门知识是建立在需要储存剩余产品基础上的。

皮特雷勒的家庭经济可以用一个再分配系统来描述,在这个系统中,一个权威机构监控生产,征用剩余产品,重新分配,并收取产生的费用。这一体系并不局限于土丘聚落及其附属的平地聚落,而是包括了邻近的其他小村庄。这是一种社会分化和等级制度,农业生产已经开始,并在很大程度上以捕鱼和后来的狩猎作为补充。

在一定程度上,皮特雷勒的剩余产品是在胁迫下生产的,但依赖暴力的制度是不可持续的。更重要的是,它需要社会凝聚力的机制,需要团结一致的时候来动员人们支持这个制度。这个经典角色是由宴飨来扮演的。成堆的食物垃圾证明了在皮特雷勒的盛宴:在探沟L发现了一堆贻贝壳,数量超过了2500。假设今天常见的贝类食物大约有12种,我们可以推断大约有200人参与了这次饕餮盛宴。

公元前4325年至4252年的皮特雷勒发现了部分保存完好的餐具和陶器,为这里曾设盛宴提供了进一步的证据。19个小杯子被安置在一个精心装饰的碗里。这一令人难以置信的发现还包括一个中等大小的碗,上面饰有漂亮的波浪纹,由小线条组成,还有几个中等大小的涂有装饰料浆的两耳细颈罐,带有塑料装饰和kumpf一样盖子的盖碗。遗憾的是,这套组合是不完整的,因为大碗的边缘和内里的杯子被卡在侧面。然而,更令人困惑的是,在这一组合中发现了以往从未见过的另外两种器型:一是25公分高的陶塑,发现于大碗一侧,二是烧过的双手上举的人形容器,饰以石墨图案。毫无疑问,这组器物因其非凡的质地和两件罕见的人形外观而被认为是特殊宴会或祭仪用品。

宴会不仅能增强集体意识,还能在提高集体工作能力方面发挥重要作用。在农业社会,劳动盛宴将有助于动员数百名工人。一顿丰盛的大餐(也许还有一两杯酒)的承诺,对那些食物资源有潜在不稳定性的社区的确起到了激励作用。两件在皮特雷勒宴会用器物中发现的人形容器,强调了这种权威的先验维度。535座人形陶塑和190座动物形陶塑,根据此类遗存的数量,我们推测这个土丘聚落不仅控制了经济活动,还有祭祀活动。即使是一类小雕像群也明显具有社会关联:在瓦尔纳墓地里,由骨头制成的大而弯曲的小雕像被认为为骨祖,只与更高社会阶层的人有关。如将这一理解应用到皮特雷勒所发现的9个骨祖上,我们就会看到皮特雷勒土丘聚落的社会阶层与瓦尔纳墓地的相同。

结论

经过15年的科学发掘,皮特雷勒令人惊喜的研究成果已经改变了我们对于罗马尼亚南部铜器时代的认知。同时,借助于放射性测年技术,我们的工作为学界揭示了古梅尔尼亚文化第一份完整的地层关系,向陶器编年的修订迈出了决定性的一步。发掘方法和技术让我们得以窥见古梅尔尼亚文化房屋建筑并确定他们生产活动中存在分化现象,这对我们理解该遗址经济和政治组织有重要意义。很明显,这个土丘是一个新的建筑,建于公元前4550年左右。对于罗马尼亚南部的许多其他同类遗存,我们认为是同时代的。可以暂时把这称为一种殖民现象。在这些新建土丘聚落的基础上,定居者不仅建立了一个具有类似生产活动的体系,而且还建立了一个持续了300多年的交流网络。

该遗址崩溃或废弃的原因尚不清楚;最后一期遗存是焚毁的,但与罗马尼亚南部其它古梅尔尼亚文化最后一期的聚落不是同时。因此,必须在更广泛的范围内评估土丘聚落的崩溃或废弃,而不是局限在当地范围内。

个人简介:

斯文·汉森,1962年生于德国的达姆施塔特,在柏林自由大学学习史前考古学,古典考古学和宗教研究;1991年获得博士学位,论文题目为《罗纳河谷和喀尔巴阡山之间的厄恩菲尔德时期的窖藏》。1994年 在罗马尼亚与德国交流委员会资助下进行了一年的学术考察,之后成为海德堡大学的一名研究助理以及波鸿鲁尔大学的助理教授,并于2000年发表《新石器时代早期–铜器时代的人性雕塑》,受聘为波鸿鲁尔大学的高级讲师。自2003年起,成为德国考古研究院欧亚研究部的主要负责人。自2004年起一直是柏林自由大学的名誉教授,硕士研究生与博士研究生导师。他的研究重心涵盖技术和社会创新之间的相互作用、社会不平等的出现以及社会和宗教层面的交流。

除皮特雷勒遗址发掘外,他在德国、格鲁吉亚和俄罗斯都有田野项目。荣获欧洲研究理事会卓越贡献奖的他锁定了高加索地区(《高加索地区的技术与社会创新:公元前4-3千年的欧亚草原与最早的城市之间》)。同时,他是苏呼米国立大学的荣誉博士及罗马尼亚科学院荣誉院士。

The slightly oval-shaped settlement mound Măgura Gorgana near Pietrele in southern Romania, with a massive circumference of ca. 255 m and E-W diameter of nearly 97 m and N-S diameter of 90 m, stood 11.5 m high in its final phase and still looms an impressive 9 m above its surroundings. In its last settlement phase, the imposing hill rose above the Danube valley, visible from afar.

Excavations in Pietrele on the Lower Danube have taken place consistently every summer since 2004 in cooperation with the Eurasia Department of the German Archaeological Institute and the Institute of Archaeology of the Romanian Academy of Sciences as well as the Institute for Physical Geography at the Goethe University of Frankfurt and have been magnanimously supported by the German Research Foundation.

According to our current state of research, life on the settlement mound lasted around 300 years between ca. 4550 and 4250 BCE. During this time period, settlement mounds in most regions of Southeastern Europe had already been abandoned. The mounds in southern Romania are not only unique in their late adaption of this type of settlement, but they differ in form from other Southeastern European settlement mounds, as well. One characteristic element is their height and steep slope, which contribute to their widespread visibility among the surrounding landscape, differing from the flat settlement mounds of the Theiss and Vinča Culture in the southern Carpathian Basin.

In the southern part of the tell, we were able to excavate a complete settlement sequence, providing us with a remarkable stratigraphical sequence measuring 11.5 m – a painstaking achievement that was understandably both technically demanding and time-consuming. The rewarding result, however, is the first complete, documented stratigraphy for the Gumelniţa Culture spanning 300 years, between 4550 and 4250 BCE.

An accumulation of 11.5 m over 300 years is very unusual; for comparison, the famous Karanovo settlement mound in Bulgarian Thrace stands 13 m high, only slightly larger than Pietrele, yet its occupation extends from the Early Neolithic to the Bronze Age. Its Level VI, contemporaneous with Pietrele, is just over 3 m in thickness.

A layer thickness of more than 11 m in Pietrele for the same period thus requires an explanation; we are, perhaps, led away from the idea of the settlement mound as the remnants of settlements and introduce the idea of the mound as monumental architecture. All over the mound, the burnt and destroyed houses were piled up with thick layer packages of material originating from the area surrounding the mound. The radiocarbon dates clearly show continuous, uninterrupted use of the settlement. Furthermore, its houses can be used as “closed contexts”, which will the basis for the description of pottery development that benefits tremendously from an inventory of over 2,500 complete vessels.

The settlement mound grew quickly, as all the burnt and unburnt houses were covered with nearly a meter of clay and sand packages before a new house was built atop them. These massive packages additionally served both to seal off older settlement layers and also to provide the necessary foundation to support a new house, whose new posts were dug into these filling layers. Life on the settlement mound was associated not only with the effort involved in the steep ascent and descent of the tell as well as repeated fires within the settlement and accompanying catastrophes, but also with the instability of the mound itself – threats of landslides and cavitation within the mound increased significantly throughout the duration of the settlement period. One could therefore conclude that the social significance of life upon the tell outweighed the inconveniences.

For a long time, the settlement mound was seen to have served as the entire settlement. One of the most important results of our research was the discovery of a substantially larger settlement at the foot of the mound, namely a flat settlement encompassing 5 ha, the limits of which have not yet been determined by geophysical surveys. Because the flat settlement existed primarily during the later phase of the settlement mound’s occupation, the question arose as to how to interpret the tell itself. One hypothesis suggests that the settlement mound served both as the nucleus of the settlement as well as a representation of social and political governance. This is perhaps best supported by the enormous density of finds and general high quality of the artifacts; for instance, metal objects have almost exclusively been found in the tell.

The beginning of the settlement mound in Pietrele dates back to ca. 4550 BCE or, according to Romanian terminology, the transition period between the Late Neolithic (Boian Culture博伊文化) and the Copper Age (Gumelniţa Culture). The few 14C dates from other settlement mounds in the region put forth a comparable picture that confirms this transition period. It follows that the settlement mound was therefore a component of a comprehensive program of new establishments; we can certainly claim Pietrele to have been a new establishment as opposed to having been borne of an existing Neolithic settlement.

Topography

From the outset, reconstruction of the 5th millennium BCE landscape was crucial to the excavations in Pietrele. Research suggested that, during this time, the Danube flowed through a larger lake, tentatively named “Lacul Gorgana”. This lake stretched approximately from the modern-day city of Giurgiu to the modern-day city of Olteniţa and was likely larger than the Bodensee. The significance of these results is not confined to the local settlement history of Pietrele, but extends much further beyond, as well. The Neolithic and Copper Age settlements sat on the edge of the terrace of the present-day meadow, what was once the former embankment of the paleolake. Pietrele, alongside other Copper Age settlements, therefore enjoyed direct access to the water and the Danube. Settlement mounds like Sultana, that seem today to sit in the “hinterlands”, were likely connected to a system of lakes.

These lakeside-dwellers were doubtless equipped with boats for mobility. The lake presented the residents of Pietrele with a significant food resource, as seen by the scores of fish remains discovered within the settlement, and it also served as an important transit system. In addition, the lakeside location illuminates the close overlapping of material culture among the Gumelniţa period settlements: these lakeside settlements on “Lacul Gorgana” essentially constituted the core of the Gumelniţa Culture, which deviates from the Thracian Karanovo Culture and from the northern Bulgarian Kodžadermen Culture in several ways.

As mentioned above, the lake provided the residents of Pietrele and its neighboring settlements with a rich source of food. The exquisite degree of preservation as well as the massive collection of recovered bones and the results gathered by wet-sieving allow for a methodologically secure basis in treating the magnitude of fishing activities that took place in Pietrele. Fish remains found in the settlement mostly include cyprinids (carp), catfish, bass and pike. Unfortunately, only a very small portion of the fishing tools and materials were preserved; nets and fish traps or wooden fishing devices that would otherwise be preserved in waterlogged settlements have long since deteriorated. But net-fishing must have been practiced frequently in Pietrele, as reflected in the massive amount of smaller fish remains.

Social Archaeology

The Copper Age in Southeastern Europe was a dynamic time period within the development of European culture. The spoils of mining and the smelting of new metal materials not only lent themselves to the naming of a new archaeological epoch, but they also doubtlessly ushered in an onslaught of the most revolutionary changes seen since the dawn of agriculture. Neither modern industry nor the technological developments that begot it would exist without metal. The immediate consequences may have been regionally confined, but they ended up being so pervasive that they had soon led to irreversible developments in many areas. Copper and gold had a particularly strong effect on developments in the Carpathian Basin and in Southeastern Europe.

The magnitude of the potential that metal offered was certainly not fully comprehensible, but the characteristics of this material undoubtedly presented significant conceptual obstacles: a material that displays such different qualities and is easy to manipulate in so many ways, able to reproduce any object perfectly, had been hitherto unheard of. Indeed, metal as a material was practically inexhaustible: once it was mined, a continuous cycle of production, use and smelting was established. With the rise of metallurgy came not only technological innovations, but also processes of social change.

Funerary finds, particularly those originating from the Varna necropolis, show a clear gradient in the wealth of grave goods that is representative of the social rank held by the deceased. The initial goal for the excavations of Măgura Gorgana was to contribute a socio-historical classification of the Varna necropolis, as the development of symbolic grave goods is comparable to the economic development of a settlement.

Artifact distribution among the houses in Pietrele contributed decisively to arguments proposing economically differentiated activities encompassing specialization and division of labor. The widespread uniformity of the material culture requires a complex system, not only in terms of exchange processes, but also in terms of production technology, with specializations extending far beyond individual settlements.

In Pietrele, relatively clear differences in artifact distribution can be determined: the houses of Trench F in the south, for instance, host the majority of hunting and fishing artifacts. Similarly, three house generations in Trench B in the north were characterized by grinding grain and textile production, testified by two weaving looms with unburnt loom weights uncovered in situ. We intend here to determine households with different economic specializations. Perhaps these activities were not practiced exclusively within these households, but the contexts do not suggest homogenous economic activity throughout the tell.

The specializations at hand suggest an awakening of new vocations from which traditions arise: potter, long-blade manufacturer and caster. Specialists did, in fact, exist during the 5th millennium BCE and are in no way a theoretical archaeological construct.

An uninterrupted sequence of eight houses in Trench F, consistently spanning over 300 radiocarbon years, presents a strong argument for hunting and fishing specialization, passed on domestically over generations. A familial tradition could be speculated here in which the children inherit and learn the vocation of their parents. Another method of establishing division of labor is to understand product manufacture. We can conclude the existence of a collaborative production process outside of the subsistence sector from an extremely complex “manual” knowledge already established during the Neolithic period that must have been passed on over generations.

Specialized knowledge is likewise assumed for the production of metal objects. The copper objects in Pietrele – totaling about 300 and consisting mostly of awls and needles and one chisel – were likely not produced on location, but originate from as yet unidentified external workshops. On the other hand, Europe’s oldest pyrotechnics of lead ores were proven to have occurred in Pietrele. Using portable x-ray fluorescence and subsequent laboratory analyses, traces of lead glance was discovered in eleven biconical vessels (“crucibles”) recovered from Pietrele. The final product of this smelting process remains unclear, but it does not appear to relate directly to the metal production process. However, large numbers of these types of vessels from Pietrele and other contemporaneous settlements and burials in Romania and Bulgaria suggest that these pyrotechnical activities were a widespread cultural practice that we can date quite precisely between 4400 and 4300 BCE.

Excavations in Pietrele have thus far uncovered ca. 13,000 flint blades and blade fragments that arrived at the settlement exclusively as finished products. Blades over 20 cm in length (so-called “superblades”) are clearly a product of specialized craftsmanship. What’s more, experimental archaeological investigations have shown that the manufacture of such high-quality blades requires extensive practice. The “superblades” were manufactured using a technique called “lever pressure” and also appear in the richly equipped burials in Varna and Durankulak as well as in settlement mounds, including a large selection from Pietrele. These blades, as mentioned above, required specialized knowledge to manufacture, a process which was likely carried out in workshops in flint mines in modern-day northeastern Bulgaria.

Even the pottery was manufactured by specialized potters, evidenced in part by large bowls decorated using imported graphite to create complex and mesmerizing patterns that almost certainly required extensive knowledge, practice and skill to execute.

Not least in the group of specialized pottery are the pithoi, enormous storage vessels, that are seen in Pietrele as products of expert craftsmanship. They serve as witnesses for the mastery of not only the technically and temporally demanding task of constructing a vessel of this size, but also of the ability to manipulate firing conditions in a kiln, knowledge that is absolutely essential in order to produce this kind of vessel. The manufacture of large-sized pottery requires much more sophisticated technology to accomplish compared to that required for the smaller utility wares.

Large storage vessels are therefore of particular interest with regard to the history of craftsmanship. Vessels of this kind in Pietrele display unique decorative patterns that are not found on the smaller vessels. It is typical of the pithoi to display a decoration that inspires a particular uncertainty in the observer, as there is no visible beginning or end to the spiral motifs.

The pithoi in Pietrele indicate both specialized workmanship as well as surplus production. These vessels could contain up to 400 liters, essentially demonstrating the most effective possible storage option for surplus production. Again, craft specialization for this particular product resulted from increased demand and could only have been maintained if the demand remained consistently high. Specialized knowledge of pithoi production was therefore predicated upon the existence of surplus production in need of storage.

The economy of the households in Pietrele can best be described by a redistributive system wherein one authority monitored production, requisitioned surpluses, redistributed them, and charged the fees incurred. This system was not limited to the settlement mound and its accompanying flat settlement, but rather encompassed other hamlets in its immediate or surrounding proximity. It was a socially differentiated and hierarchical system in which agricultural production took place, supplemented in large part by fishing and, in later periods, hunting.

The surplus in Pietrele was to a certain extent generated under physical coercion, but a system dependent on violence is unsustainable. Much more, it required mechanisms of social cohesion, of solidarity-affirming moments that mobilize people to work in favor of the system. This is the classic role played by feasting. Feasting in Pietrele is evidenced by large piles of food waste: in Trench L, a pile of mussel shells was found that numbered over 2,500. If we assume that today’s common shellfish portion contains about a dozen, we can extrapolate that about 200 people could have participated in this meal.

An exceptional, partially preserved collection of tableware and crockery found from the final settlement period in Pietrele – ca. 4325-4252 BCE – offers further evidence for feasting in Pietrele. In this collection, 19 small cups were nestled inside an elaborately decorated bowl. This incredible find also contained a mid-sized bowl with a beautiful wave motif consisting of little lines as well as several mid-sized amphorae with barbotine decoration, tureens with plastic ornamentation and “kumpf”-like vessels with accompanying lids. This feature is unfortunately incomplete, as the edge of the large bowl and its cups was stuck into the profile. More perplexing in this feature, however, are two other uncommon vessel forms that have perhaps never before been discovered within the same feature: the first is a clay figurine, 25 cm in height, found lying beside the large bowl, the second is a burnt anthropomorphic vessel with raised arms, decorated with graphite patterns. This magnificent ensemble of vessels doubtless served as special feasting or cult equipment due to its phenomenal quality and the appearance of two rare anthropomorphic vessels.

Feasting not only reinforces a sense of community, but it can also play an essential role in boosting collective working capacity. In agrarian communities, work feasts would help mobilize hundreds of workers. The promise of a hearty meal – perhaps also a spirit or two – did wonders to motivate any community with potentially precarious food resources.

The presence of both anthropomorphic vessels within the feasting ensemble in Pietrele emphasizes the transcendental dimensions of such authority. The comparatively high number of 535 anthropomorphic and 190 zoomorphic statuettes allows us to imply that the settlement mound controlled not only economic, but ritual activities as well. Even individual groups of statuettes apparently possess social relevance: the large, curved figurines made of bone – interpreted as phallus depictions – are associated in the Varna necropolis exclusively with people belonging to a higher social class. Applying this finding to all nine phallic bone figurines in Pietrele would suggest that the same social class lived on the settlement mound in Pietrele that was represented in the graves in Varna.

Results

The exceptional results gathered after 15 years of excavation prove that research in Pietrele has changed the picture of Copper Age settlements in southern Romania. Our work has, among other things, awarded the research community with the first complete Gumelniţa stratigraphy with solid radiocarbon dates and taken a decisive step towards a revision of the pottery chronology. Our methods and excavation techniques have allowed us to gather valuable insight into the construction of Gumelniţa houses as well as determine their differentiation in production activities, thereby contributing enormously to our knowledge of economic and political organization on the settlement mound. It is clear that this mound was a new establishment, founded around 4550 BCE. For many other tell settlements in Southern Romania, we assume a similar foundation date. We may tentatively be able to claim this as a type of colonization. With the foundation of these new mounds, the settlers established not only a system of similar settlements with comparable production activities, but also an exchange network that persisted for over 300 years.

Reasons for the settlement’s collapse or abandon remain unclear; the final settlement phase was burnt down, but should nevertheless be contemporaneous with the final settlement phases of all other Gumelniţa settlements in southern Romania. The collapse or abandonment of the settlement mound must therefore be assessed within a wider context as opposed to on a local scale.

Biographic Sketch

Svend Hansen, born 1962 in Darmstadt, studied at the Free University in Berlin Prehistoric Archaeology, Classical Archaeology and Religious Studies. He received his PhD in 1991 with a thesis entitled, “Hoards of the Urnfield Period between the Rhône Valley and Carpathians”. Following his one-year travel stipend from the Römisch-Germanische Kommission in 1994, he worked as a research associate at Heidelberg University and as an assistant professor at the Ruhr-University in Bochum where, in 2000, he habilitated with his work, “Studies on Early Neolithic and Copper Age Figural Sculpture” and was appointed with the title of Senior Lecturer. Since 2003, he has served as the Primary Director of the Eurasia Department of the German Archaeological Institute. He has served as an honorary professor at the Free University in Berlin since 2004, where he also supervises numerous Master and doctoral students. At the center of his research is the interplay between technical and social innovations, the emergence of social inequality and the social and religious dimensions of exchange.

In addition to the excavations in Pietrele, he has carried out field research in Germany, Georgia and Russia. The Caucasus is also the geographical focus of his Advanced ERC grant (Technical and Social Innovation in the Caucasus: Between the Eurasian Steppes and the Earliest Cities in the 4th and 3rd millennia BC). He received an honorary doctorate from Sukhumi State University and is an honorary member of the Romanian Academy.