克罗斯-纳克索斯的海上航道与卡沃斯沿海腹地的青铜时代早期圣所

The Keros-Naxos Seaways and the coastal hinterland of the Early Bronze Age sanctuary at Kavos

伦福儒、迈克尔·博伊 Colin Renfrew and Michael Boyd

(英国剑桥大学 University of Cambridge)

引言

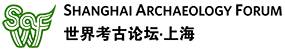

卡沃斯位于基克拉泽斯群岛中的克罗斯小岛的西端(图1),数十年来一直是希腊最神秘的考古遗址之一。新的田野调查改变了我们对该岛在爱琴海早期青铜时代的中心作用的认识。前期的工作已经将卡沃斯定义为世界上最早的海上圣所之一。 2016-2018年在相邻小岛达斯卡里奥上的发掘表明,该地点在公元前2500年左右急剧扩张,伴随着纪念性建筑的建造和工艺实践尤其是冶金的集中化。这些因素,加上该地点的特殊覆盖范围(来访者最远来自希腊大陆,距离西部约200公里)和生存基础的变化,说明了在城市化的初期发展时,其等级和等级社会关系发生了重大变化。目前正在进行中(的)对考古发现的研究和阐释,正在改变我们对公元前三千年地中海东部的社会变迁的理解,这是在米诺斯克里特宫殿及其代表的复杂社会和宗教组织出现之前的关键时刻。对这些新数据的分析将为理解在世界范围内, 在定期聚会场所进行的仪式在促进广泛的社会变革中的作用做出巨大贡献。(对这些新数据的分析,将为理解在世界范围内定期聚会场所的宗教仪式对促进广泛的社会变革方面的作用作出重大贡献。)

克罗斯的重要性

自十九世纪末以来,公元前三千年的数个大理石雕塑(现在在卢浮宫和雅典国家考古博物馆中)的发现使得克罗斯为人所知。 1960年代(20世纪60年代),伦福儒在克里斯托斯·杜马斯的建议下访问了该岛的西端,发现了一个被洗劫一空的场所,乍一看似乎像是一座墓地。希腊考古局于1963年和1967年在抢劫区进行的抢救性挖掘工作中,发现了许多破碎的大理石雕塑,大理石容器和陶瓷。 1987年对该地区进行的一次小规模调查表明,这些遗迹已超出了被洗劫的范围,这为2006年至2008年之间开展的一项重大研究项目提供了动力。

从2006年发掘的第一天起,在掠夺者未触及的地方新发现的破碎的大理石(图2)为了解这个不寻常的遗址的性质提供了机会。发掘表明,这些并非是墓地的遗物,而是经过特意放入的精心挑选的破碎的大理石。此外,在大多数情况下,每个原始对象仅由破碎后选择的单件物品表示(每件原始物品都仅代表破损后选出的一件物品):破裂发生在其他地方,在基克拉泽斯群岛其他岛屿上,而人们将已经破碎的材料带到该地点。这项历久弥新的仪式为岛上各族群之间维持了近半个世纪的集会中心提供了证据,从而创造了世界上最早的海上圣所。

2006-2008年的项目还集中在附近的达斯卡里奥发掘(图3)。达斯卡里奥如今是一个小岛,位于卡沃斯以西约90m(90米)处,但深海测深法研究表明,在青铜时代初期,它通过一个低洼的陆桥与卡沃斯相连,本身就形成了一个适合将当时使用的独木舟和长艇系留的港口。在达斯卡里奥最高处的发掘工作发现了一系列目的不明确的建筑。碳十四测年和陶瓷类型学表明了该出占领的三个阶段:阶段A(公元前2750年-2550年),阶段B(公元前2550年-2400年)和阶段C(公元前2400-年(年–)2250年)。卡沃斯的两处“特殊沉积物”中的大部分活动似乎都追溯到了A期,而在达斯卡里奥上发现的大部分活动似乎都追溯到了C期。

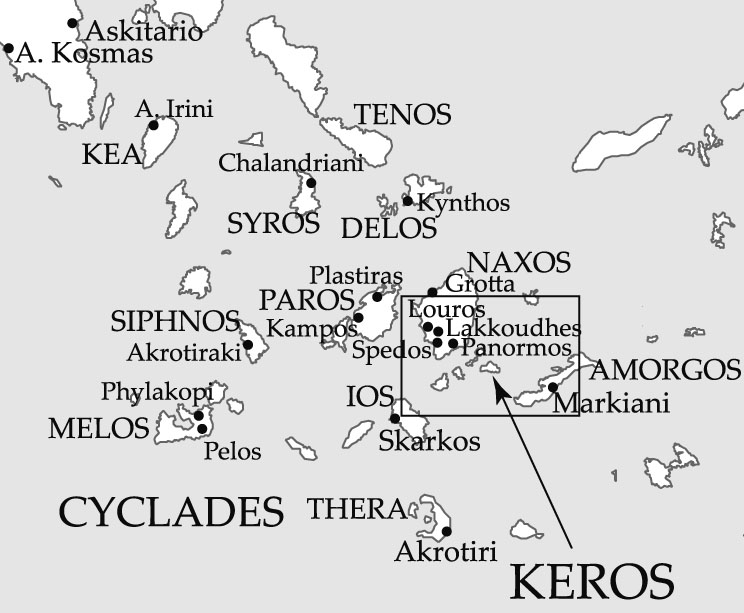

在2012-2013年,对克罗斯岛进行了步行调查,以更多地了解圣所的腹地和该岛的农业潜力。调查显示,尽管其缺乏自然资源和耕地,但在克罗斯却安置了比预期更多的定居点,有力地表明了新的耕作策略(特别是使用梯田和将生存基础扩大到包括种植橄榄和葡萄)被用来提高该岛的农业潜力。卡沃斯的圣所和达斯卡里奥的建筑物不是完全孤立的,而是在圣所建立的同时,在克罗斯上建立的居住等级制度达到了顶峰。

2015-2018年项目

2015年至2018年之间开展的新工作扩大并加深了对克罗斯的调查范围,从而对克罗斯独特遗址的形成,全盛和废弃产生了标量性的认识。

目的与方法

该项目的目的是调查克罗斯保护区的更广阔区域及其在人员,资源和物资网络中的作用;并了解达斯卡里奥遗址的性质,范围和年代。

为了了解克罗斯在更广泛的基克拉泽斯群岛中的角色,采用了两种方法。首先,对邻近的加藤·库菲尼西岛(距开罗斯5公里,是最近的具有农业潜力的重要岛屿)进行了调查,并在更大的纳克索斯岛的东南海岸进行了调查。这样做的目的是通过对附近大量土地进行采样并在爱琴海创建第一个相邻的海事调查区,来扩大已经在克罗斯上进行过调查的克罗斯腹地的面积。希望能够理解一些重大问题,例如在多大程度上利用附近的岛屿来开发其资源,特别是挖掘其农业潜力;纳克索斯岛和加藤·库菲尼西的定居模式与已经在克罗斯确立的定居模式相比如何?达斯卡里奥和卡沃斯是否位于共同区域的居住体系的顶端,或者在这些相邻区域中是否存在其他重要地点。最后,为了测试地表调查的结果,计划在克罗斯进行调查的两个地点进行试探性发掘。

了解克罗斯在爱琴海网络中的作用的第二种方法是通过资源和材料进行特征研究。在先前的工作中已经确定,在克罗斯使用的所有材料和资源都是从其他岛屿或更远的地方进口的。关于陶器,石材,黑曜石以及可能还有的其他有机资源的新的特征分析工作,可能会加深我们对广泛领域物质和资源交换的程度和强度的了解。

聚焦达斯卡里奥(以达斯卡里奥为中心),以(先)前的工作提出了重要问题,最近活动旨在回答这些问题。整个海角在多大程度上被建筑物占据?定居点的起源是什么,它随着时间的推移而均匀扩展或以点状的形式爆发,是什么导致了它的废弃?该遗址的功能是什么,特别是该遗址比简单的家庭住所更专门化吗?

为了解决这些问题,我们采用了一种全新的方法。重点是将专家研究实时纳入到发掘方法中,并在整个团队中分层传播数据。为此,使用了运行在iPad上的iDig应用程序的完全数字记录方法(图4)。 iDig是为记录雅典广场的发掘中的发掘数据而开发的,但我们对其进行了重新调整,以便将专家研究中的所有数(据与)发掘数据结合在一起,从而促进专家,发掘者和执行团队之间的自思性。微观形态学家和土壤化学家等现场专家将其结果直接记录在与发掘者相同的数据库中,并将田野的实验室研究(尤其是陶器和环境数据)记录在同一数据库中。尤其是对陶器研究进行了设计,以便由六名专家组成的小团队在发掘 后的第二天就可以研究材料,从而为发掘者提供有关其发掘环境的即时反馈。

田野发掘时使用开放区域和单一背景系统下进行发掘。开放区域的方法很重要,因为必须有大的沟渠才能了解建筑物和综合体建筑的本质,和在建筑物之间以及通过为支撑建筑而建的下层露台设置移动路线的方式。单一背景方法对于了解遗址和各个房间的,尤其是对遗址的地层学理解至关重要。替代传统的开放区域和单一背景依赖于平面图,使用数字摄影测量法实现了体积记录方法。通过摄影测量记录每个背景 ,从而创建了发掘的庞大3D档案,并通过检查每个背景的3D模型来对挖掘中的每个步骤进行检查。

结果与阐释

对纳克索斯岛和对加藤·库菲尼西岛的调查(图5)显示,与克罗斯一样,青铜时代是这些岛屿有最多人居住的三个时期之一(另外两个时期是罗马早期拜占庭时期和最近一个时期)。但是检测到了差异。在早期的青铜时代,加藤·库菲尼西岛似乎和克罗斯一样密密麻麻。然而,东南纳克索斯州的居住格局却不那么密集。这两个地区都有重要的遗址,尽管没有达斯卡里奥大。这表明在一定距离上,达斯卡里奥和卡沃斯是该时期最重要和最大的地点,但是纳克索斯岛和加藤·库菲尼西岛则是二级居住地点。陶瓷的研究在将完全进口的克罗斯陶瓷与两个相邻区域中本地陶瓷与进口陶瓷的比例进行比较中将被证明具有极高价值。

在达斯卡里奥上开了9条挖掘沟,最大的沟渠覆盖25m x 9m(图6)。 达斯卡里奥的规划者和建造者建造了一系列巨大阶地,以创造平坦的建筑空间,因为整个岛屿的坡度都很陡。我们在岛的北侧和东侧放置了沟槽来调查这些构造(图7)。在所有的挖掘沟中都发现了令人印象深刻的建筑特色。其中包括主要的入口,其中一个似乎是该地点的主要入口(图8),从达斯卡里奥和卡沃斯之间的堤道向上延伸,由一条穿过巨大的梯田壁的阶梯组成。同样,通过巨大的上层阶地墙到达山顶的路线,是由大型建筑走廊中的一组阶梯形成的。在其他地方,路径由石板组成,其中一个小正方形形成一个节点(图9),而一个巨大的阶梯则形成另一个(节点)。在数个沟渠中发现了复杂的排水系统。这些特征表明,由同心的阶地系统组成的预先计划的建筑综合体为建筑物的建造创造了水平区域。

发掘的大部分区域都在B期内,这是该发掘的重要发现:B阶段发生了以达斯卡里奥为特征的建筑活动的显着增加。2016-2018年的发掘总体上发现了约551平方米,其中大部分被挖掘到深处,在坍塌的石头下面揭示了建筑物的墙壁,建筑物的地板,在那里进行的活动的残留物,在许多情况下还包括早期的地板甚至早期的建筑。建筑石料是从约10公里远的纳克索斯进口的。为了获得所需的材料(包括至少5000吨的进口石材),这一危险的旅程被重复了数百次。建筑的质量,根据规划的程度以及实现它们所需的工作量,为我们研究社会性质打开了一个新窗口。巨大的带有入口和排水系统的建筑阶地展现了整个海角规划建设的远景,这一计划显然已经实现,建筑面积约1.3公顷,是当时基克拉泽斯最大的土地。

居住性质的证据来自可以发现的活动类型。其中最重要的是冶金学(图6、10)。在D(删除)达斯卡里奥工作中最显着的方面之一是,在每个沟槽中都发现了金属加工的证据,并采用了不同的技术工艺。冶金学似乎是达斯卡里奥最早的活动,冶金炉床设在基岩中,其后仍留在三个沟渠中。这些用于铜的熔化和物体的铸造。发现了用于矛头的模具(图10)和匕首。后来,当建筑覆盖整个岛屿时,在两个沟渠中设有大量的作坊。事实证明,铅和银可能与铜一起工作,而金(在早期青铜时代基克拉泽斯群岛中极为罕见)在五个挖掘沟中被发现,其中包括可能用于修整金属文物的金线和金箔。金属加工的证据强度和活动范围在基克拉泽斯早期都是空前的。我们才刚刚开始理解达斯卡里奥遗址的性质及对更广泛的爱琴海社会,流动性,身份和权力的影响。

总体而言,发掘工作和相关的勘测为通向不断变化的世界打开了一扇窗户。信息交流的新模式和新媒介被部署在网络中,这些网络后来被集会活动在中心点克罗斯维持下来,在那里,人们树立了对社会的新视野。现在,我们可以认识到克罗斯在公元前第三个和第二个千年的历史轨迹中所处的位置,克罗斯与克里特岛的克诺索斯一起代表了中心位置的第一个预兆,这在几百年后变得很普遍。在公元前2200年之后在克里特岛的爱琴海地区开始城市化之前,现在可以在克罗斯 识别其先例。诸多因素共同构成了即将在其他地方进行的城市化进程的独特预示:集中化,即一个中心脱颖而出;非凡的影响力,将遥远社区的成员吸引到了以克罗斯为中心的网络中;金属生产,农业和建筑等领域的集约化发展;强化,体现在杰出的建筑项目中,按普遍的标准具有纪念意义;以及强大的仪式组成部分,吸引了来自各地的参与者,并为所有其他流程奠定了基础。证据还表明,伪造和维护特定基克拉泽斯身份的新方法主要集中在克罗斯上。这种身份的关键元素包括基克拉泽斯雕塑,基克拉泽斯的“偶像”(图标)以及重要的实践,例如航海和金属加工,尤其是在达斯卡里奥生产和使用匕首。

结论

直到最近,我们对基克拉泽斯早期青铜时代的描述主要是基于墓地发掘,抢救性的发掘以及可疑的盗劫物品。在克罗斯上的工作已经完全改变了整个图景。 纳克索斯岛的克罗斯海上航道计划的特点是致力于全面出版这个雄心勃勃的项目,其范围广泛,由跨学科和多学科的专家参与,共分四册,并发表大量学术文章。关于克罗斯和早期基克拉泽斯世界的知识很多,这促使了它产生和变化。最近,通过新闻文章,纪录片和最近的博物馆展览引起了公众的关注(图11)。出版计划将在接下来的两年中花费我们的全部精力,然后我们希望进一步扩大我们的工作。到目前为止,仅达斯卡里奥遗址已被挖掘出10%(只有大约10%的达斯卡里奥遗址被挖掘出来,)而且(删除)对早期基克拉泽斯生活的更多理解必定仍在其表面之下(停留在地表之下)。

柯林·伦福儒,于1965年获得英国剑桥大学博士学位,1965-1972年任教于谢菲尔德大学,1972-1981年任教于南安普敦大学。1981至2004年间,伦福儒教授供职剑桥大学,任迪斯尼考古教授。伦福儒教授在希腊基克拉迪群岛主持了大量考古发掘工作。他在爱琴海史前文化、语言多样性起源和人类认知、考古遗传学和考古理论等研究领域取得了举世瞩目的成就。伦福儒长期以来不遗余力地推动反对非法倒卖文物及 盗掘的国际运动。伦福儒教授已出版多本著作:文明之前:放射性碳革命和史前欧洲(1973),考古学和语言:印欧起源之谜(1987),考古学:理论方法与实践(保罗巴恩并著,1991年第一版,2016年第7版),掠夺,合法性和所有权:考古学的伦理危机(2000),史前史:人类思想的形成(2008),除此之外还有许多合著。因其在基克拉迪群岛的重要发掘、富有深远影响力的理论研究,以及在提升公众对濒危文化遗产的保护意识方面的不懈努力,伦福儒教授已屡获殊荣,其中包括1980年被选为英国科学院院院士,1991年获凯姆索恩·伦弗鲁男爵终身贵族称号,1996年当选为美国科学院外籍院士,2003年获得欧洲科学基金会欧洲拉丁奖,2004年荣获与诺贝尔奖齐名的巴尔扎恩奖,2007年被选为美国考古学会外籍荣誉会员和2009年获得文物保护组织SAFE灯塔奖。2015年获得世界考古论坛终身成就奖。

迈克尔·博伊,剑桥大学麦克唐纳考古研究中心研究员,主要从事史前伯罗奔尼萨半岛和希腊基克拉迪群岛的研究,他协助主持了克罗斯–纳克索斯海上航道项目,也是克罗斯系列出版物的协编者。他曾在希腊、保加利亚和阿尔巴尼亚等地进行考古工作。他与约翰巴瑞特合著了《从巨石阵到迈锡尼:考古学阐释的挑战》一书。他与科林伦福儒、伊恩莫雷共同主编了关于从世界范围内讨论死亡和墓葬考古的书籍,另外还有关于戏剧和宗教仪式的平行发展的作品。他还与阿纳斯塔西亚合作编辑了《分期死亡》,与玛丽莎和科林伦福儒共同编辑了《早期基拉科迪群岛雕塑》。自2008年,他与科林伦福儒合作出版了克罗斯2006~2008年发掘报告,五本报告中的四本已经发表。他还编辑了关于克洛斯群岛调查的出版物,该调查于2012-2013年间进行,预计即将在2020年面世。他作为克罗斯–纳克索斯海上航道项目的共同主持者,参与了克罗斯发掘工作(2016-2018),纳克索斯调查工作(2015)和 基克拉泽斯的调查(2018)。田野工作已在2018年完成,随后将有4卷相关出版物。

Introduction

Kavos, at the western end of the small island of Keros in the Cyclades (Fig. 1), was for decades one of the most enigmatic archaeological sites in Greece. New fieldwork has transformed our understanding of the island’s central role in the Early Bronze Age Aegean. Earlier work had already defined Kavos as the world’s earliest maritime sanctuary. Excavation in 2016-2018 on the adjacent islet of Dhaskalio demonstrated the site’s dramatic expansion around 2500BC, with planned monumental constructions and centralisation of craft practices, especially metallurgy. These factors, combined with the exceptional reach of the site (visitors came from as far as the mainland of Greece, some 200km to the west) and changes in the subsistence base, point to incipient urbanisation with major changes in hierarchical and heterarchical social relations. Study and interpretation of the finds, currently ongoing, are changing our understanding of social transformations in the third millennium BC eastern Mediterranean at the crucial point just before the appearance of the palaces of Minoan Crete and the complex social and religious organisations they represent. The analysis of these new data will make a great contribution to understanding the role of ritual practices at periodic meeting places worldwide in catalysing wider social change.

The Importance of Keros

Keros has been known since the late nineteenth century when several marble sculptures of the third millennium BCE were found (now in the Louvre and in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens). In the 1960s Colin Renfrew visited the west end of the island at the suggestion of Christos Doumas and found an extensively looted site that at first glance might have seemed like a cemetery. Rescue excavations carried out by the Greek Archaeological Service in the looted area in 1963 and 1967 recovered much broken marble sculpture, marble vessels, and ceramics. A small survey of the area carried out in 1987 suggested the remains extended beyond the looted area and this provided the impetus for a major research project carried out between 2006 and 2008.

From the first day of excavation in 2006, new finds of broken marble (Fig. 2) in an area untouched by looters offered the opportunity of understanding the nature of a clearly unusual site. The excavations showed that, far from being the remains of a cemetery, these were deliberate deposits of carefully selected broken material. Moreover, in most cases each original object was represented by only a single piece selected after breakage: the breakage had taken place elsewhere, and the site was a place to which people brought material already broken elsewhere, on other islands of the Cycladic archipelago. This long-lived ritual provides evidence for a centre of congregation maintained between island communities over nearly half a millennium, thereby creating the world’s earliest maritime sanctuary.

The 2006-2008 project also focused on excavating nearby Dhaskalio (Fig. 3). This is today a tiny islet located some 90m west of Kavos, but bathymetric studies showed that in the Early Bronze Age it was joined to Kavos by a low-lying landbridge, itself forming a harbour suitable for beaching the canoes and longboats used at that time. Excavations on the summit of Dhaskalio uncovered a series of buildings whose purpose was not clearly domestic. Radiocarbon dates and ceramic typology suggested three phases of occupation: Phase A (2750-2550BCE), Phase B (2550-2400BCE), and Phase C (2400-2250BCE). Most of the activity in the two ‘special deposits’ on Kavos seemed to date to Phase A, while most of the activity uncovered on Dhaskalio seemed to date to Phase C.

In 2012-2013 a pedestrian survey of the island of Keros was carried out in order to understand more about the immediate hinterland of the sanctuary and the agricultural potential of the island. The survey showed that, despite its lack of natural resources and arable land, rather more settlement than might have been expected was located on Keros, strongly suggesting that new farming strategies (particularly the use of terraces, and the expansion of the subsistence base to include the olive and the vine) were employed to improve the agricultural potential of the island. The sanctuary at Kavos and the buildings on Dhaskalio, rather than being entirely isolated, were rather at the pinnacle of a settlement hierarchy established on Keros at the same time as the founding of the sanctuary.

The 2015-2018 Project

New work carried out between 2015 and 2018 both widened and deepened the scope of the investigation of Keros, leading to scalar insights into the inception, floruit and abandonment of the unique site of Keros.

Aims and Method

The aims of the project were to investigate the wider area of the Keros sanctuary and its role in networks of people, resources and materials; and to understand the nature, extent and chronology of the site on Dhaskalio.

In order to approach Keros’ role in the wider Cyclades, two approaches were employed. First, survey was conducted on the neighbouring island of Kato Kouphonisi (5km distant from Keros, and the nearest significant island with agricultural potential), and further distant on the southeast coast of the much larger island of Naxos. The aim here was to extend the area of the Keros hinterland already surveyed on Keros itself by sampling a significant extent of nearby land and creating the first adjacent maritime survey zone in the Aegean. The hope was to be able to understand significant questions, such as to what extent nearby islands were exploited for their resources and particularly for their agricultural potential; how the occupation patterns on Naxos and Kato Kouphonisi might compare with those already established on Keros; and whether Dhaskalio and Kavos were at the top of the settlement hierarchy for the combined area, or whether other significant sites existed in these adjacent areas. Finally, in order to test the results of surface survey, test excavations were planned on two sites identified by survey on Keros.

A second approach to understanding Keros’ role in Aegean networks is through resource and material characterisation studies. It was already established in previous work that all materials and resources used on Keros were imported from other islands or from further afield. New characterisation work on pottery, stone, obsidian and, potentially, on organic resources, might further our understanding of the extent and intensity of material and resource exchange over a wide area.

Focusing on Dhaskalio, important questions arose from previous work which the recent campaign was designed to answer. To what extent was the entire promontory occupied with buildings? What were the origins of the settlement, did it expand evenly or in punctuated bursts over time, and what led to its abandonment? What were the functions of the site, and in particular was the site rather more specialised than a simple domestic settlement?

In order to approach these questions, an entirely new methodology was adopted. The emphasis was on the integration of specialist studies in real time into the excavation methodology and on the dissemination of the data heterarchically throughout the team. To that end, an entirely digital recording methodology was adopted, using the iDig app running on iPads (Fig. 4). iDig was developed for recording excavation data at the Agora excavations in Athens, but we repurposed it so that all data from specialist study could be integrated with the excavation data, thus facilitating reflexivity between specialists, excavators and the executive team. Field specialists such as the micromorphologist and soil chemist recorded their results directly into the same database as the excavators, and field laboratory studies, especially pottery and environmental data, were recorded in the same database. In particular, pottery study was designed so that a small team of six specialists could study material the day after excavation, thus giving excavators immediate feedback on the nature of the contexts they were excavating.

Excavation in the field was undertaken using the open-area, single-context system. The open-area approach was important in that large trenches were necessary in order to understand the nature of the architecture of buildings and complexes, and the way that routes of movement were set between buildings and through the underlying terraces built to support the architecture. The single-context approach was essential in order to understand the taphonomic history of the site and individual rooms, and in particular to develop the stratigraphic understanding of the site. Replacing the traditional open-area and single-context reliance on plan drawings, a volumetric recording method was effected using digital photogrammetry. Every context was recorded photogrammetrically, creating a vast 3D archive of the excavation, and allowing the review of each step in the excavation by examining the 3D model of each context.

Results and Interpretation

The surveys on Naxos and Kato Kouphonisi (Fig. 5) showed that, as on Keros, the Early Bronze Age was one of the three periods during which these islands were most inhabited (the other two being the late Roman-Early Byzantine period, and recent times). However differences were detected. Kato Kouphonisi appears to have been as densely inhabited as Keros during the Early Bronze Age. Southeast Naxos, however, shows a less dense occupation pattern. Both areas have important sites, though none as large as Dhaskalio. This suggests that Dhaskalio and Kavos were by some distance the most important and largest sites of the period in this wider area, but that second order sites were present on Naxos and Kato Kouphonisi. Study of the ceramics will prove invaluable in comparing the entirely imported ceramics of Keros with the proportion of local to imported ceramics in the two adjacent areas.

Nine excavation trenches were opened on Dhaskalio, the largest covering 25m x 9m (Fig. 6). The planners and builders of Dhaskalio constructed a series of massive terraces to create flat spaces for building, since the incline is steep all over the island. Our trenches were placed to investigate these constructions at several levels on the north and east side of the island (Fig. 7). Architecturally impressive features were uncovered in all of the trenches. These included major entranceways, one of which appears to be the main entrance of the site (Fig. 8), leading up from the causeway between Dhaskalio and Kavos, formed of a set of stairs piercing a monumental terrace wall. Similarly the route to the summit through the most monumental of the upper terrace walls is formed by a set of stairs in a massively built corridor. Elsewhere paths were made of flagstones, with a small square forming one nodal point (Fig. 9) and a monumental stair set forming another. Complex drainage systems were found in several trenches. These features suggest a pre-planned complex consisting of concentric terracing systems which created level areas for the construction of buildings.

The greater part of the area excavated falls within Phase B, and this is an important discovery of the excavation: the remarkable explosion of building activity that characterises Dhaskalio occurred during Phase B. Overall the excavation of 2016-2018 has uncovered some 551 square metres, much of it excavated to depth, revealing underneath collapsed stone the walls of the buildings, their floors, the material remains of the activities carried out there, and in many cases earlier floors or even earlier architecture. Building stone was imported from Naxos, some 10km distant. This hazardous journey was repeated many hundreds of times to obtain the required material, comprising at least 5000 tonnes of imported stone. The quality of the constructions, the degree of planning they evidence, and the amount of labour required to realise them, has opened a new window onto the nature of the society which we are investigating. The massive building terraces with entranceways and drainage systems show a vision for the planned construction of the whole promontory – a plan that was evidently achieved, with buildings extending over an area of about 1.3 ha, the largest site of its time in the Cyclades.

Evidence for the nature of the occupation comes from the types of activities which can be detected. The most important of these is metallurgy (Figs. 6, 10). It is one of the most remarkable aspects of the work on Dhaskalio that evidence for metalworking was found in every trench, with different technical processes represented. It would appear that metallurgy was the earliest activity on Dhaskalio, with metallurgical hearths set in the bedrock underneath later remains in three trenches. These were for the melting of copper and the casting of objects. Moulds for spearheads (Fig. 10) and daggers have been found. Later, when the constructions covered the island, extensive workshops were located in two trenches. Lead and perhaps silver working is evidenced alongside copper, while gold – extremely rare in the Early Bronze Age Cyclades – was found in five trenches, including gold wire probably used for finishing metal artefacts, and gold foil. Both the intensity of evidence for metalworking, and the range of activities, is unprecedented in the early Cyclades. We have only begun to understand all the implications of the nature of the site at Dhaskalio for wider Aegean society, mobility, identity and power.

Overall, the excavations and the associated surveys have opened a window onto a changing world. New modes and media of information exchange were deployed in networks that came to be sustained by acts of congregation at a central point, Keros, where a new vision for society was crafted. We can recognise now the place of Keros in a certain historical trajectory of the third and second millennia, where Keros represents, along with Knossos on Crete, the very first premonition of the central places that would become common just a few hundred years later. Prior to the inception of urbanisation in the Aegean on Crete after 2200BC, its antecedents may now be recognised here at Keros. A number of factors combine in a unique foreshadowing of the processes of urbanisation soon to take place elsewhere: centralisation, whereby one centre stands out above all contemporaries; exceptional reach, where members of far-flung communities were drawn into networks centred on Keros; intensification, evidenced in spheres such as metal production, agriculture and architecture; aggrandisement, seen in exceptional architectural programmes which are monumental by prevailing standards; and a strong ritual component, drawing in participants from far and wide and underpinning all the other processes. The evidence also suggests that new means of forging and maintaining a particular Cycladic identity were centred on Keros. Key elements in this identity included Cycladic sculpture, the ‘icon’ of the Cyclades, along with important practices such as seafaring and metalworking, and in particular the production and use of daggers on Dhaskalio.

Conclusion

Until recently, our picture of the Cycladic Early Bronze Age was based largely on cemetery excavations, hurried rescue excavations, and dubious looted material. Work on Keros has completely changed this picture. The Keros-Naxos Seaways programme is characterised by a commitment to full publication of an ambitious project, wide in its scope, with the participation of inter- and multi-disciplinary specialists, in four volumes and numerous academic articles. Much has been learned about Keros and the Early Cycladic world which brought it into being and which it changed beyond recognition. This has recently come to public attention through press articles, documentaries and a recent museum exhibition (Fig. 11). The publication programme will take all of our energy for the next two years, and then we will hope to expand our work further. Only about 10 per cent of the Dhaskalio site has been excavated so far, and many further insights into Early Cycladic life must surely remain below its surface.

Biographic Sketch

Colin Renfrew received his doctorate in 1965 from the University of Cambridge. After the post as a Lecturer and then Reader at the University of Sheffield (1965-1972) and the Professorship at the University of Southampton (1972-1981), Renfrew was elected in 1981 to the Disney Professorship of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge, a post he held until 2004. Professor Colin Renfrew has directed a number of major excavations on the Cycladic islands in Greece. He has made remarkable contributions to Aegean prehistory, origins of linguistic diversity and human cognition, archaeogenetics, and archaeological theory. In addition, Professor Colin Renfrew has been one of the leading figures in the international movement to prevent the illicit antiquities trade and associated looting of archaeological sites. Professor Colin Renfrew has authored numerous books; among them are Before Civilisation: the Radiocarbon Revolution and Prehistoric Europe (1973); Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of the Indo-European Origins (1987), Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice (with Paul Bahn, 1st edition, 1991; 7th edition, 2016); Loot, Legitimacy and Ownership: The Ethical Crisis of Archaeology (2000); Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind (2008); and many co-authored books. Professor Renfrew’s eminent career, made up of both important excavations on the Cycladic islands, influential theoretical insights, and tireless and dedicated efforts in raising public awareness about our endangered cultural heritage, has been rewarded with many distinguished honors, awards and prizes. Among them are Fellow of the British Academy (1980), a life peerage as Baron Renfrew of Kaimsthorn (1991), Foreign Associate to the National Academy of Sciences of the USA (1996), the Latsis Prize of the European Science Foundation (2003), the Balzan Prize (less well known than the Nobel but equally prestigious, 2004), Foreign Honorary Member of the Archaeological Institute of America (2007), and the SAFE Beacon Award (2009). Professor Colin Renfrew was presented to the first SAF Lifetime Achievement Award in 2015.

Michael Boyd is a senior research associate at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge. His main research interests lie in the prehistoric Aegean where he has worked in the Peloponnese and Cyclades. He is co-director of the Keros-Naxos Seaways project, and co-editor of the Keros publications series. He has worked widely in Greece, Bulgaria and Albania. He is co-author with John Barrett of the volume From Stonehenge to Mycenae: the challenges of archaeological interpretation. He is co-editor with Colin Renfrew and Iain Morley of a volume on the archaeology of death and burial from a worldwide perspective, and another on the parallel development of play and ritual. He is also co-editor with Anastasia Dakouri-Hild of Staging Death, and is co-editor of Early Cycladic Sculpture in Context, with Marisa Marthari and Colin Renfrew, and Beyond the Cyclades. Since 2008 he has worked with Colin Renfrew on the publication of the Keros excavations of 2006 to 2008, of which he is co-editor. Four of a planned five volumes have now been published. He is also editing the publication of the Keros Island Survey, carried out and completed in 2012 and 2013, and due to be published in 2020. He is co-director of the Keros-Naxos Seaways project, involving excavation on Keros (2016-2018), survey on Naxos (2015), and survey on Kato Kouphonisi (2018). Fieldwork was completed in 2018 and publication will follow in four further volumes.