非洲撒哈拉以南玻璃的考古研究

Archaeology of Glass in Sub-Saharan Africa

阿比德米·巴巴洛拉 Abidemi Babatunde Babalola

(英国剑桥大学 University of Cambridge)

尽管玻璃是人类发明的最年轻的材料,但玻璃还是古代最值得崇拜和最有价值的物品之一。它的显著特性是其他较早的材料所不具有的,例如半透明性、颜色变化和自然光泽或可能是其价值体现的主要原因。在美索不达米亚叙利亚和伊拉克附近发现了大约公元前2500年最早的人造玻璃之后,该地区及其周围地区就取得了很多的研究成果。这些努力使得在近东地区发现了更多的玻璃制造中心。早期的玻璃是用两种主要原材料制成的:硅酸盐材料与盐生植物的熔剂。但是,随着玻璃知识的进一步发展和传播,引入了不同的新原料,在一定的时间框架内,玻璃的成分从一个区域到另一个区域发生了变化。因此,在伊斯兰世界大约在公元前800年发明了钠或矿物苏打玻璃,大约在公元800年罗马/中世纪的欧洲发明了木灰玻璃,大约在公元前1000年中国发明了铅钡玻璃,并在公元前一世纪南亚发明了小苏打–氧化铝玻璃。玻璃技术长时段的发展过程中,是在撒哈拉以南非洲的什么地方呢?有意思的是,这些各种成分的玻璃都是从撒哈拉以南的非洲考古遗址中发现的,其中发现的最早的玻璃(以珠子的形式)可追溯到公元前400-600年的波斯,即现代马里的尼伯地区。非洲次大陆上玻璃的出现强有力的证明了玻璃并非本土制造的,而是跨区域交流互动的产物。然而,在撒哈拉以南非洲地区发现的一些二次加工玻璃的手工作坊证明会对进口玻璃进行重新加工和回收利用。早在公元6-17世纪,奇布恩就有一个关于早期玻璃加工的证据。尽管有玻璃加工的证据,但仍然存在问题,比如撒哈拉以南非洲地区是否存在初级玻璃加工?撒哈拉以南非洲地区在玻璃发展和生产的版图中处于什么位置?尼日利亚西南部埃勒–伊夫遗址(Ile-Ife)的发现解决了这些问题。

地理学与考古学背景下的埃勒–伊夫遗址

埃勒–伊夫遗址位于尼日利亚西南部的森林地带。它位于几个山岭和山脊建筑群的中心,导致其地形被描述为“凹”形。埃勒–伊夫位于山脚和山脊的平面上,这使得它容易被侵蚀,因为在流入主河道的一条支流之前,要先经过埃勒–伊夫遗址。这也意味着,山脚和山脊下的土壤富含很多养分,宜耕种,考古证据也表明,早期农业聚落一定聚集在山脚下。

从考古学上讲,埃勒–伊夫遗址以其铜合金铸造、陶俑和石雕方面的非凡艺术作品而闻名。埃勒–伊夫遗址的艺术作品中的自然主义和其制作的复杂性一方面显示了其创作者的能力,另一方面也将其与从古埃及、努比亚到希腊、罗马古典艺术等全球其他地区著名雕刻传统相媲美。一些考古和艺术的历史证据表明,公元12至15世纪是早期伊夫(Ife)文明的顶峰,也被称为“古典时代”。除了陶瓷制造、铜合金铸造、炼铁、复杂城市规划和修建路面、玻璃和玻璃珠制造等手工业专业化的扩展,古典时代的特征还在于复杂的城市生活和集中的政治制度。因此,埃勒–伊夫发展成为地区性大国,并且直到公元15世纪晚期,埃勒–伊夫都是该地区的政治和经济中心。

尽管我们对埃勒–伊夫遗址早期的艺术行业相当关注,我们毫不怀疑他们发展或从事复杂技术的能力,但对玻璃行业的研究较少有人关注。尽管与玻璃相关的产业和埃勒–伊夫早期可能存在玻璃工业的想法早在一个多世纪前就已经有了,但对这项技术详细的研究的尚待全面开展。这种疏忽可能部分是因为古代玻璃制造研究被次大陆的考古学所垄断,排除了撒哈拉以南非洲地区。此外,玻璃在埃勒–伊夫的出现,尤其是在伊博·奥洛昆地区的出现,被看作是玻璃二次加工的典型代表。

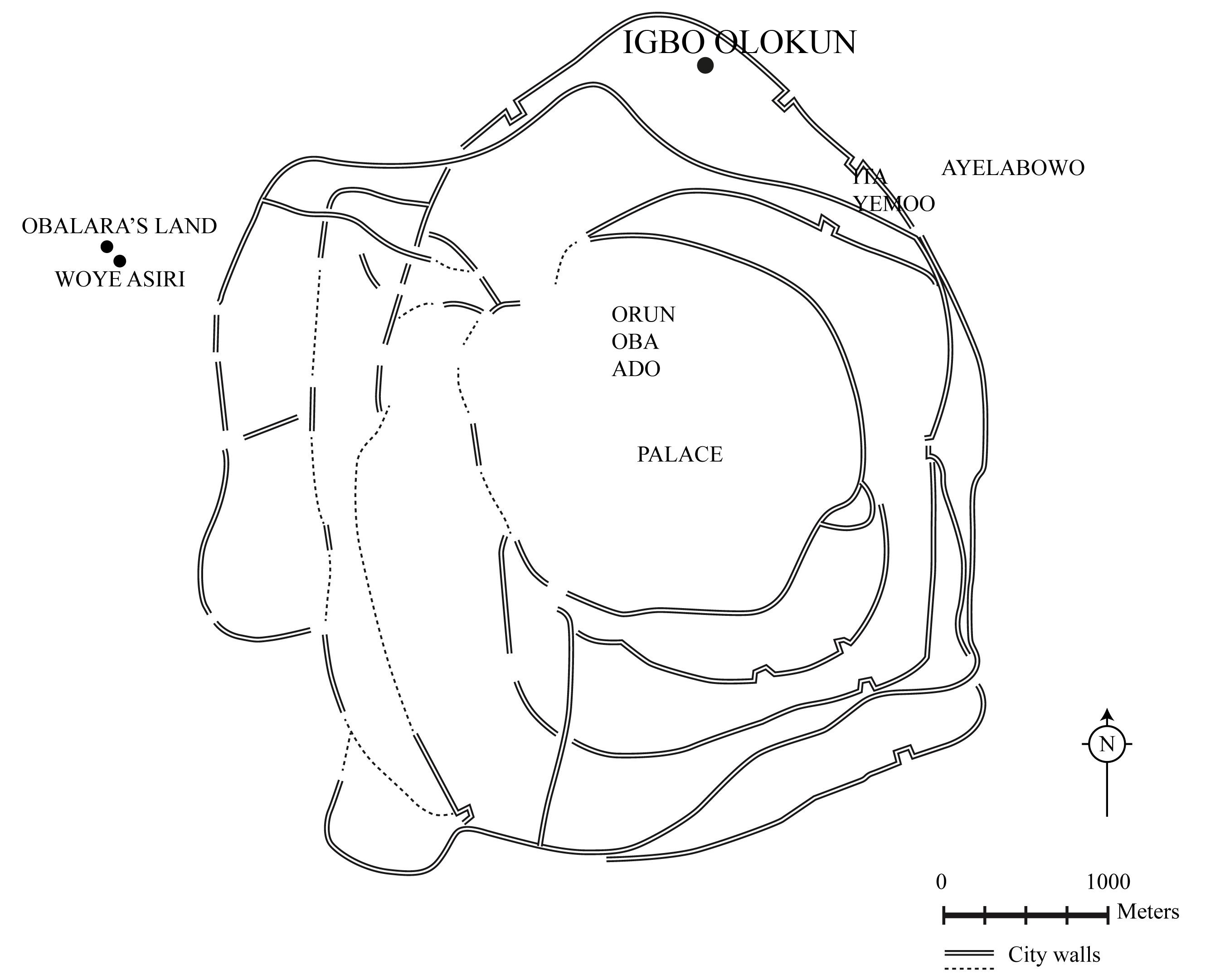

伊博·奥洛昆是遗址所在地,在文献中被普遍称为奥洛昆森林,它位于埃勒–伊夫市北部。几十年来,因为在地表发现大量散落的玻璃材料,所以当地居民都认为这个地方很可能是玻璃制造或某种工作的作坊。1910年一个叫利奥·弗罗本尼斯的德国人造访了埃勒–伊夫,他不仅参观了该遗址,还雇佣当地人帮他挖掘这个遗址以及整个城市的其他树林。他向世人公布他发现了几只玻璃器皿,现在已知是玻璃坩埚,以及碎玻璃和玻璃珠。20世纪50年代,殖民考古学家伯纳德·法格先生发掘了伊博·奥洛昆,他也是尼日利亚古代部的第一任主任。20世纪60年代初,1957年应邀在伊塔耶摩发掘的英国考古学家弗兰克·威利特也曾在20世纪50年代末至60年代初的时候在伊博·奥洛昆进行过发掘。奥莫托索·埃鲁耶米是第一位在该遗址工作的尼日利亚考古学家。他在20世纪70年代末至80年代期间在伊博·奥洛昆进行了一系列考古调查。尽管大量的玻璃制品可以帮助我们了解古代埃勒–伊夫的玻璃技术,但之前在该遗址的所有调查大多集中在艺术品上,很少甚至根本没有关于玻璃工业的报道。然而,只有埃鲁耶米报道了在伊博·奥洛昆发现了玻璃材料,但是很有限。埃鲁耶米也认同古代埃勒–伊夫掌握了本土玻璃制造技术的观点。由于缺乏足够的证据来支持这一观点,他的观点没有引起重视。如今,伊博·奥洛昆是伊夫博物馆主持下的一个纪念碑遗址,它是尼日利亚国家博物馆和古迹委员会的一个部门。

玻璃考古研究项目:在埃勒–伊夫市伊博·

奥洛昆的发掘

我们在遗址的工作主要是调查和发掘。2010~2017年,我们在遗址挖掘了15个单位,面积约为31平方米。一些单位集中在遗址的一个位置以便了解空间组织,而另一些单位则分布在遗址的不同位置,以划定古人活动范围,并更好地了解文化堆积的厚度。在发掘范围内,文化层从70 厘米~135 厘米不等,它被云母含量高的黄红色红土壤覆盖。黄红土壤的这些特性与该地区下层的土壤相吻合。在少数情况下,我们发掘了红土层,但没有发现任何人工制品。在许多其他情况下,我们并没有挖掘到红土层,表明它是人类最初的活动面。我们发现了三个相连的灰坑和一个狭窄的通道。我们在1.1米处到达其中一个连体坑的底部。灰坑壁是直的,底部是平的。其中一个连体灰坑较浅,底部距红土地面约50cm。从灰坑底部采集的木炭样本测年结果为公元11世纪。我们无法到达第三个坑的底部。关于这些灰坑经常被问的问题是,它们能否被确定为现场熔炉的一部分?尽管没有在撒哈拉以南非洲发现早期的初级玻璃制造熔炉作为先例,来帮助比较这里的玻璃制造熔炉,但灰坑的结构和布置表明,它们很可能是遗址内制造和加工玻璃的废址。

伊博·奥洛昆发掘的遗物中大部分材料与工业有关,包括坩埚碎片、玻璃珠、玻璃废料、陶器碎片和其他陶瓷材料。这些遗物都是覆盖红土层下和灰坑中的。我们在伊博·奥洛昆发掘了大量丰富而多样的遗物,这些遗物能够帮助我们更好的调查玻璃的来源、使用的原材料和生产技术等。芝加哥菲尔德博物馆的劳雷杜苏比厄博士一直负责对玻璃材料进行LA-ICP-MS分析。分析了120多个玻璃样品,包括废玻璃、玻璃珠和坩埚玻璃。Thilo Rehren教授利用光学显微镜和SEM-EDS对坩埚和其他生产相关材料的研究,有助于了解坩埚织物的微观结构以及附着的内玻璃和外釉的化学成分。在卡塔尔基金会的慷慨资助下,我们得以在卡塔尔多哈的伦敦大学学院材料科学实验室分析一些样品。塞浦路斯研究所考古和文化科学技术研究中心(STARC)的材料科学实验室正在分析更多的样品,这要感谢Leventis基金会资助这部分项目。这些分析的结果为我们提供了宝贵和压倒性的证据,支持在撒哈拉以南地区首次发现初级玻璃制造业的论点。我将在下一节讨论结果。

坩埚、玻璃珠、生产废料和半成品玻璃

在我们的发掘过程中,发现了不同类别的材料,这些材料表明了伊博·奥洛昆存在工业活动。发掘出了1500多个坩埚碎片。发现的不同部位如边缘、主体和底座等可以拼接出完整的坩埚容器。坩埚可以是椭圆形的,也可以是筒形的,高度从16厘米~35厘米不等。壁厚在1.5厘米~4厘米之间,底部是坩埚最厚的部分。坩埚中最明显的元素是内部的玻璃镶嵌物。内璧玻璃的颜色包括蓝色和绿色、红色和无色。蓝色和绿色是内玻璃中最常见的颜色。从技术上看,我们已经证明坩埚是专门用于高温活动而被制造出来的。坩埚粘土中高浓度的氧化铝证明了它们的耐火性。这样,坩埚就可以承受1300℃以上的温度而不软化。因为盖子的碎片也被找到了,也可以证实大多数坩埚都是有盖子的。盖子是半球形的,上面有三个孔,用来插入铁棒来提起盖子。

在伊博·奥洛昆的发掘中,已经找到了20000多颗玻璃珠。玻璃珠组合的独特性不在于数量,而在于种类的多样性,包括成品珠和半成品珠。玻璃珠的颜色与坩埚玻璃的颜色一致,但黄色除外,只有黄色的玻璃珠,而没有黄色的坩埚。大多数珠子是单色的,蓝色最常见,绿色次之。多色珠子大多是有条纹的。多色珠中的另一组,我们称之为“无色涂层红色”,该组由无色核心的珠子组成,外部有红色涂层。在这个组合中,基本上可以辨别出三种形状:圆柱形、扁圆形和管状。玻璃珠非常小,大多数小于5毫米。这种微小的珠子使得它们在视觉上可以与所谓的“种子珠”相媲美,但它们的化学性质不同。与玻璃珠和坩埚玻璃一样,发掘出的生产碎片中,蓝色是最常见的颜色。因此,发掘出4公斤以上的玻璃废料。废物组合分类表明,它们不仅与玻璃珠组合有关,而且清楚地表明了伊博奥洛昆玻璃珠制造的连锁经营模式。成分分析进一步确定了这些发现类别之间的联系。

半成品玻璃是考古遗址玻璃制造的最有力证据之一。撒哈拉以南非洲的考古遗址没有发现半成品玻璃的实物资料证据。事实上,在青铜时代晚期的埃及,只有少数车间发现了半成品玻璃的证据。在我们2017年初的调查中,由AHG(玻璃史协会)资助,目的是研究早期我们在伊博·奥洛昆发掘出的一块底部粘有大块物质的坩埚底座,现收藏于NHM(自然历史博物馆)。通过对这种物质及其属性的检测我们可以清楚知道,它是一块半成品玻璃,它质地脆,有很多气泡。初步的显微和后向散射图像检查以及回声测探分析表明,基质是不均匀的,存在长石、硅灰石和富钴相,且含有明显的未熔石英颗粒。这些分析表明是一个未完成的过程(这些分析可以证实这是半成品玻璃)。

为什么埃勒–伊夫遗址早期玻璃制造的证据是一个独特的发现?

要回答上述问题,首先要问一个问题:是否有初级的玻璃生产,有什么证据。第一步是确定伊博·奥洛昆在生产哪种玻璃。如前所述,我们对100多个玻璃样品进行了化学分析,其中包括坩埚玻璃、玻璃珠和玻璃碎片。分析表明,玻璃中氧化铝含量高,钠锰含量低。钠和锰的低浓度表明,玻璃既不是伊斯兰苏打石灰,也不是中世纪欧洲木灰玻璃的起源。高石灰、高氧化铝(HLHA)占分析样品的85%以上。另一组低石灰、高氧化铝(LLHA)也存在。还有第三类,低石灰中等氧化铝(LLMA),似乎微不足道。这些组的颜色是可区分的,蓝色、绿色和无色的阴影是高石灰、高氧化铝的,红色和黄色的阴影主要是低石灰、高氧化铝的,很少是低石灰中等氧化铝。这些组分在玻璃珠、坩埚玻璃和碎片中都可以识别,表明它们都属于同一个玻璃制造传统。高氧化铝和高氧化铝玻璃的成分与富含长石的伟晶岩和蜗壳的组合一致。将埃勒–伊夫遗址的高石灰、高氧化铝玻璃的化学成分与该地区的地质成分进行比较,发现地质支持这种化学特征。因此,埃勒–伊夫遗址玻璃是当地配方的产品。詹姆斯·兰克顿、阿金·伊格和蒂洛·雷伦是第一个在分析的埃勒–伊夫玻璃珠集合中识别高石灰、高氧化铝组的人。他们的工作集中在未经证实的博物馆收藏和在埃勒–伊夫收集或购买的样品上。然而,他们能够认识到高石灰、高氧化铝玻璃在世界各地已知的古代玻璃成分组中的独特性。他们的结论是,高石灰、高氧化铝玻璃必须是在埃勒–伊夫内部或附近本地制造的。该项目提供了考古学证据,将这种玻璃技术牢固地归因于埃勒–伊夫,该作坊位于伊博奥洛昆。该站点专门用于生产高石灰、高氧化铝玻璃。

伊博·奥洛昆的坩埚用于玻璃制造和玻璃加工。坩埚粘土的高度耐火性和一些坩埚在使用过程中留下的裂纹表明,它们所涉及的温度远远超过了现有玻璃再熔化所需的温度。坩埚玻璃基质中保存的石英颗粒证明了原材料(而不是现成的玻璃)被送入坩埚的事实。在大多数坩埚中都可以观察到代表“刮痕”的单向槽,这是在舀出熔融玻璃的剩余部分时留下的痕迹。这些刮痕和大量的生产废料支撑玻璃制造的工作。

在撒哈拉以南的非洲地区,没有一个地方有如此令人难以置信的证据,能够证实在与欧洲接触之前,人们就已经发现了制造最初玻璃的方法。这一发现可能是次大陆众多有待发现的发现中的第一个,它彻底改变了我们对玻璃在全球的发展和传播的认知,尤其是改变了该地区考古学中关于西非森林带的一些认知。例如,我们现在知道,玻璃的发明并不局限于世界某一地区,而是具有区域性特征的。根据对环境和可用原材料的了解,不同地区发明了不同的玻璃。高石灰、高氧化铝玻璃的发明使森林地带成为早期技术研究的焦点。此外,与所有名贵物品都是由北方进入森林的观念相反,现在很明显的是,南部森林埃勒–伊夫地区也十分积极的向撒哈拉贸易发达地区输送玻璃珠等珍贵物品。在马里的埃索克·特德马卡和高等贸易城市也发现了埃勒–伊夫市的高石灰、高氧化铝玻璃珠。

最后,从最初开始,该项目研究的主要目标之一就是能让当地社区参与我们的工作。考古学在埃勒–伊夫遗址中解开的大多数早期技术的知识目前濒临灭绝,因为当地只有少数人知道过去确实存在过这项技术。我们准备通过耳濡目染来吸引当地人们的注意,其中一个方法就是组织参观一次现场图片展,并展示发掘出的玻璃文物。这个策略引起了路人的注意,许多路人停下来和我们聊天。国王伊芙奥尼的访问是该研究的一个转折点(感谢阿迪萨·奥贡弗拉坎教授为访问提供了便利)。在他与随行人员的访问中,我们对他们介绍了大约1000年前在埃勒–伊夫遗址生产的本地玻璃制造历史的相关研究。他们惊讶且好奇地想知道更多。言下之意,这次访问打开了通往社区中心的大门,使我们的工作合法化,使我们在当地有了知名度和更多接触真相的机会。国王一直支持这座城市的所有考古研究工作。

个人简介

阿比德米·巴巴洛拉是英国剑桥大学非洲研究中心的Smuts研究的研究员,也是麦当劳考古研究所的研究员。在加入剑桥大学之前,他是哈佛大学人类学系的研究员,哈佛大学哈钦斯非洲和非裔美国人研究中心的麦克米兰·斯图尔特研究员。他还是塞浦路斯研究所考古和文化科学技术研究中心的一名研究人员。巴巴洛拉博士是尼日利亚埃勒–伊夫市早期玻璃生产考古项目的负责人。他的新项目侧重于调查沿西尼日尔走廊的手工业专业化和复杂社会。他的研究兴趣包括早期技术、复杂社会中的手工业专业化、早期城市化、政治经济。他的文章发表在《古物》、《非洲考古》、《考古科学》和《非洲人研究》等刊物上。他曾在美国、坦桑尼亚和尼日利亚参与研究。他在休斯顿莱斯大学获得博士学位,在尼日利亚伊巴丹大学获得硕士和学士学位。

Although the youngest of the materials invented by human, glass is one of the most adorable and valuable objects in antiquity. The attribution to its striking characteristics that were not seen in other earlier materials such as its translucency, the colour variation, and the luster nature among others may be responsible for its valuation. Following the discovery of the first man-made glass from Mesopotamia around Syria and Iraq at about approximately 2500 BC, substantial scholarships have been devoted to the region and its environs. These efforts led to the encountering of more glass making centers in the Near East including Bet She’ arim, Tell Brak, Tell el-Amarna, Al-Raqqa among others. The first glass was made with two major raw materials: siliceous material flux with halophytic plant. However, as the knowledge of glass develop further and spread, different and new raw materials were introduced, and the composition of glass was changing from one region to another within a temporal framework. Hence natron or mineral soda glass was “invented” at about 800 BC in the Islamic world, the Roman/medieval European wood ash glass at around 800 AD, the Chinese lead-barium glass at about 1000 BC, and the south Asia natron soda-alumina glass approximately first century BC. Where is sub-Saharan Africa in this longe duree of the development of glass technology? Interestingly, glass of all these compositional groups have been found from archaeological contexts across Sub-Saharan Africa with the earliest (in form of bead) being of Persian origin dated to 400-600 BC at Nin-Bere in modern-day Mali. The occurrence of glass on the sub-African continent has strongly established regional and trans-continental interaction with the outside world rather than an indication of indigenous glass making. However, a couple of secondary glass-working workshops where the imported glass was reworked and recycled have been identified across sub-Saharan Africa. An example of early evidence of glass-working came from Chibuene dated to 6th-17th century AD. Despite this evidence of glass working, the question remains, was there primary glassmaking in Sub-Saharan Africa? Where does sub-Saharan Africa fit in this larger picture of the development and production of glass? The discovery at Ile-Ife, southwest Nigeria addresses these questions.

Ile-Ife in Context: Geography and Archaeology

Ile-Ife is in the forest belt of southwest Nigeria. It lies at the center of several hill and ridge complexes which leads to its topography being described as “bowl” shape. The location of Ile-Ife on the plane at the foot of the hills and ridges makes it susceptible to erosion because the runoff from the hill sweeps through the city before it drains into the tributaries of one of the major rivers that traverse Ile-Ife. By implication, the soils at foot of the hills and ridges are rich in nutrient and suitable for farming, archaeological evidence has suggested that, perhaps, early farming communities must have congregated at the hill foots.

Archaeologically, Ile-Ife is famous for its extraordinary artworks in copper alloy casting, terracotta figurines, and stone carving. The naturalism of Ile-Ife artworks and the intricacies of their production allude to the prowess of their makers on the one hand and match them up with other well-known sculpting traditions across the globe from ancient Egypt, Nubia, to the classic Greek and Roman arts. Several archaeological and art historical evidence pointed at the 12th through 15th century AD as the peak of early Ife civilization – also known as “classical era”. In addition to the proliferation of craft specialization in ceramic making, copper alloy casting, iron making, complex city planning and construction of potsherd pavements, and glass and glass bead making, the classical era is also characterized by complex urban living with centralized political system. Thus, Ile-Ife developed as a regional power that was at the center of the political and economic affairs in the region – status it held until late 15th century AD.

While considerable attention has been on the art industry in early Ile-Ife with no ambiguity regarding her capacity to develop or engage in sophisticated technologies, study of the glass industry has received less traction. Although glass-related objects and the idea of possible viable glass industry in early Ile-Ife has been around for over a century, the whole complex of the technology is yet to be fully investigated. This neglect may be, in part, due to the fact that a narrative that excluded Sub-Sahara African in the studies of ancient glass making has been privileged in the archaeology of the Sub-continent. Furthermore, the occurrence of glass in Ile-Ife, particularly, at Igbo Olokun is interpreted to represent secondary glass working.

Igbo Olokun, the site this project, is popularly referred to in the literature as Olokun grove. It is located in the northern sector of the city of Ile-Ife. The site has been known to the local inhabitants for decades as probably a workshop of glassmaking or working of some sort because of the abundant glass materials that litter the surface of the site. Leo Frobenius, the German who visited Ile-Ife in 1910, visited the site and paid the locals to dig for him at the site as well as in other groves across the city. He reported encountering several glazed vessels, which are now known to be glass crucible, as well as cullet, and glass beads. Bernard Fagg, the colonial archaeologist and the first director of the Nigerian Department of Antiquity, excavated at Igbo Olokun in 1950s. In early 1960s, Frank Williett, a British Archaeologist who was invited to excavate at Ita Yemoo in 1957, also conducted excavations at Igbo Olokun in late 1950s or early 1960s. Omotosho Eluyemi was the first Nigerian archaeologist that worked at the site. He conducted a series of archaeological investigations at Igbo Olokun between late 1970s and 1980s. Despite the abundance of glass artifacts that may help us understand the technology of glass in ancient Ile-Ife, all the previous investigations at the site focused mostly on artworks and reported little or nothing on the glass industry. However, only Eluyemi reported on the glass materials from Igbo Olokun, howbeit limited. Eluyemi also championed the narrative of possible indigenous glassmaking in classic Ile-Ife. His voice was overshadowed because of lack of enough evidence to substantiate this claim. Today, Igbo Olokun, is a monument site under the auspices of Ife Museum, which is a division of the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM).

The Archaeology of Glass Project: Excavations at Igbo Olokun Ile-Ife

Igbo Olokun has proved worthwhile for the study of glass production in classic Ile-Ife. Hence, our archaeological exploration at Igbo-Olokun and its environs commenced in 2010. Since inception of the project it has benefited a lot from several organizations and institution for funding. These include Rice University’s Social Science Research Institute (SSRI), Corning Museum of Glass, Association of the History of Glass (AHG), UCL Qatar, McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research – University of Cambridge, Leventis Foundation, Cyprus Institute, Cambridge-Africa ALBORADA and the British Museum. These institutions and organizations have contributed immensely to the progress and success of the research. I should also state that local institutions such as the Department of Archaeology & Anthropology, University of Ibadan, and Obafemi Awolowo University’s Natural History Museum (NHM) have been of tremendous assistance. We have also received unalloyed support from the local community as well as several individuals who have offered valuable services and intellectual contributions over the course of the project.

Our activities at the site have centered on reconnaissance survey and excavations. Between 2010 and 2017 we have excavated a total of 15 units within the site amounting to an area of approximately 31 square meters. While some of the units concentrated within a location at the site to understand the spatial organization, others were sunk in different locations across the site to delineate the extent of the activity area and to have a better sense of the depth of the cultural deposition. The cultural layer varies from 70 cm to 135 cm in the excavated units, which is underlaid by a yellowish-red lateritic soil with heavy mica content. These characteristics of the yellowish-red soil match the sub-soil in the region. In few cases we dug into the laterite layer, but no artifact was recovered. In many other cases we did not dig into the laterite layer as it suggest an initial industrial surface where activities were carried out. We uncovered three conjoined pits and another with a narrow channel. We reached the bottom of one of the conjoined pits at about 1.1 meters. The wall of the pit is straight with a flat bottom. One of the conjoined pits is shallower with the bottom reached about 50cm from the surface of the laterite floor. A charcoal sample from the bottom of the shallow gave a date of 11th century AD. We could not get to the bottom of the third pits. The question that came up often regarding the pits is that can they be identified as part of the furnaces at the site? Although there is no precedent for an early primary glass-making furnace in sub-Saharan Africa to help with the comparison of furnaces, the structure and arrangement of the pits suggest that they are likely to be ruins of the infrastructure for glass making and working at the site.

The cultural deposit at Igbo Olokun is significantly rich in industrial-related materials including crucible fragments, glass beads, glass wasters, potsherds, and other ceramic materials. These artifacts are common to both the cultural deposit overlaying the laterite and the pits. The abundance and variety of the materials recovered from our excavations at Igbo Olokun allow different form of analysis to investigate the source(s) of the glass, raw materials used, and the technology of production among others. Dr. Laure Dussubieux of the Field Museum, Chicago, has been in-charge of LA-ICP-MS analysis of the glass materials. Over 120 glass samples including wasters, glass beads, and crucible glass have been analyzed. Professor Thilo Rehren has been helpful in working on the crucibles and other production-related materials with the use of Optical Microscope and SEM-EDS to understand the microstructure of the crucible fabric and the attached inside glass and outer glaze as well as to determine their chemical constituent. With the generous funding from the Qatar Foundation, we were able to analyze some samples at the material science laboratory of the University College London, Doha Qatar. More samples are being analyzed at the material science laboratory facility of the Science and Technology in Archaeology and Culture Research Centre (STARC) of the Cyprus Institute – thanks to Leventis Foundation for funding this part of the project. Results of these analyses have provided us with an invaluable and overwhelming evidence to support the argument for the first discovery of a primary glassmaking industry in Sub-Saharan. I will discuss the results in the next section.

Crucibles, Glass Beads, Production Waste, and Semi-finished Glass

Materials of different categories that indicate industrial activities at Igbo Olokun were retrieved during our excavations. Over 1,500 crucible fragments were recovered. The assemblage represents different parts of the crucible vessels: rim, body, and base. The crucibles are either oval or barrel with height varying from 16 cm to 35 cm. The wall thickness range between 1.5 cm and 4 cm with the bottom being the thickest part of the crucibles. The most conspicuous element of the crucible is the inlay of glass on the interior. The color of the inner glass includes shades of blue and green, red, and colorless. Blue and green are the most common color among the inner glass. We have been able to demonstrate that the crucibles were technically designed for specific use in high heat activity. The high concentration of alumina in the crucible clay attests to their refractory nature. Thus, the crucible would have withstood temperature above 1300OC without soften. Most of the crucibles are lidded as fragments of lids were also recovered. The lids are hemispherical in shape with three holes on the upper part, which would have been used for inserting iron rod to lift the lid.

Over 20,000 glass beads have been retrieved from the excavations at Igbo Olokun. The uniqueness of the glass bead assemblage is not in the quantity but in the varieties of categories therein, which include finished and unfinished beads. The colors of the glass beads match that of the crucible glass except for yellow, which is only present among the beads but not seen in the crucible. Most of the beads are monochrome with blue being the most common followed by green. The polychrome beads are mostly striped. A different group among the polychrome is a group I called “colorless coated red.” This group consists of beads of a colorless core with red coating on the exterior. There are basically three shape categories discernible in the assemblage: cylindrical, oblate, and tubular. The glass beads are extremely small most of which are less than 5mm. This tiny nature of the beads makes them visually comparable to the so-called “seed bead,” but they are chemically different. Like the glass beads and the crucible glass, blue is the commonest color among the production debris recovered from the excavations. Hence, over 4 kilograms of glass wastes were recovered. Classification of the waste assemblage reveals that they are not only connected to the glass bead assemblage but also clearly indicated the chaine operatorie of glass bead making at Igbo Olokun. Compositional analysis further established the connection among these categories of finds.

Semi-finished glass is one of the strongest evidence of glassmaking in an archaeological site. No archaeological site in Sub-Saharan African has yielded evidence of semi-finished glass. In fact, only a few workshops yielded evidence of semi-finished glass in Late Bronze Age Egypt. During our early 2017 investigation, funded by AHG, aimed at studying materials earlier excavated or collected at Igbo Olokun curated in the storage facility of the NHM, we encountered a piece of crucible base with a chunky substance stick to the bottom. Examination of the substance and its attributes clearly suggest to us that it is a chunk of semi-finished glass. It is brittle in texture with lots of bubbles. Preliminary microscopic and backscatter image examination, as well as EDS analysis, show that the matrix is heterogenous with the presence of feldspar, wollastonite, and cobalt-rich phases with significant unmelted quartz grains. These phases indicate an unfinished process.

Why is the Evidence of Glassmaking in Early Ile-Ife a Unique Discovery?

To answer the above question, we must first ask whether there was primary glass production in the first place or not, and what are the evidence. The first way is to determine what kind of glass was being produced at Igbo Olokun. As mentioned earlier, we have chemically analyzed over 100 glass samples, which include crucible glass, glass beads, and glass debris. The analysis shows that the glass is high in alumina with low sodium and manganese. The low concentration of sodium and manganese suggests that the glass is neither of the Islamic soda-lime nor the medieval European wood-ash glass origin. A group with high lime, high alumina (HLHA) is dominant representing over 85% of the analyzed samples. Another group with low lime, high alumina (LLHA) is also present. There is a third group, low lime moderate alumina (LLMA), which appears to be insignificant. These groups are distinguishable by colors such that shades of blue, green, and colorless are of the HLHA and red and yellow are mostly of the LLHA, and rarely of the LLMA. These compositional groups are recognizable in the glass beads, crucible glass and the debris suggesting that they all belong to the same glassmaking tradition. The composition of the HLHA and LLHA glass is consistent with the combination of feldspar rich pegmatite and snail shell. A comparison of the chemical composition of Ile-Ife HLHA glass with the geological component in the region reveals that the geology supports such a chemical signature. Therefore, Ile-Ife glass is a product of local recipes. James Lankton, Akin Ige, and Thilo Rehren were the first to identify the HLHA group among an assemblage of Ile-Ife glass beads analyzed. Their work centered on unprovenanced museum collection and samples collected or purchased at Ile-Ife. However, they were able to recognize the uniqueness of the HLHA glass among the known ancient glass compositional groups from across the globe. They conclude that the HLHA glass must have been locally made within or near Ile-Ife. This project has provided archaeological evidence to firmly ascribe this glass technology to Ile-Ife with the workshop located at Igbo Olokun. This site was exclusively dedicated to the production of the HLHA glass.

The crucibles at Igbo Olokun were used in both glass making and glass working. The highly refractory nature of the crucible clay and the cracks that some of the crucibles sustained in the process of use suggest that they were involved in temperature that far exceeds what is needed for re-melting of existing glass. The preserved quartz grains in the glass matrix of a crucible is a testament to the fact that raw materials, as opposed to ready-made glass, were fed into the crucible. Observable in most of the crucible are unidirectional grooves representing “scrape mark,” which is the mark left behind when the leftover of molten glass was been scooped out. These scrape marks with the abundance of the production waste support glass working.

Nowhere in sub-Saharan Africa has such incredible evidence of primary glass making, prior to the European contact, been discovered. This discovery may be first of the many waiting to be uncovered in the sub-continent, the discovery has revolutionized what we know about the development and spread of glass globally and specifically shifted some narratives about the forest belt of West Africa in the archaeology of the region. For example, we now know that the invention of glass was not limited to a particular region of the world, rather it was regional. Different regions invented different glass based on the knowledge of the environment and the available raw materials. The invention of the HLHA glass put the forest zone in the spotlight in the study of early technologies. Also, contrary to the notion that all prestige items came from the north into the forest, it is now evident that Ile-Ife a southern forest community was actively contributing valuables such as glass beads to the complex commercial networks of the trans-Saharan exchange. Ile-Ife HLHA glass bead has been found in trading cities such as Essouk Tedmakka and Gao in Mali among others.

Lastly, from the outset, one of the main objectives of the project is to be able to engage the community in our work. The knowledge of most of the early technologies that archaeology has unraveled at Ile-Ife are currently endangered because only a few people in the community know that such material knowledge existed in the past. One of the ways we were about to pass our massage and draw the attention of the local community was to organize an onsite photo exhibition and display of samples of the excavated materials. This strategy drew the attention of passersby many of which stopped to have a chat with us. The visit of Ooni of Ife, the King, was a turning point for the project (Thanks to Professor Adisa Ogunfolakan for facilitating the visit). During his visit with his entourage, we worked them through the archaeology and history of indigenous glassmaking in Ile-Ife dated to about 1000 years ago. They were not only wowed but also became curious to know more. By Implication, the visit opened the doors to the hearts of the communities, it legitimized our work and gave us visibility in and access to the community. The King has always been supportive of all archaeological projects in the city.

Biographical Sketch

Abidemi Babatunde Babalola is the Smuts Research Fellow at the Centre of African Studies, University of Cambridge United Kingdom where he’s also a Fellow of the McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research. Before joining Cambridge, he was a Fellow in the Anthropology Department at Harvard University and the McMillan-Stewart Fellow at the Hutchins Center for African and African-American Research, Harvard University. He is also a Research affiliate at the Science and Technology in Archaeology and Culture Research Centre of the Cyprus Institute. Dr. Babalola is the Director of the archaeological project on early glass production in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. His new project focuses on investigating craft specialization and complex societies along the West Niger corridor. His research interest includes early technologies, craft specialization in complex society, early urbanism, political economy. His articles have appeared in Antiquity, Journal of African Archaeology, Journal of Archaeological Science and Journal of Black Studies. He has participated in research in the United States, Tanzania, and Nigeria. He received his PhD from Rice University, Houston, and his M.A and B.A from the University of Ibadan, Nigeria.