本土悠悠:拉奎玛达和墨西哥西部七世纪至十四世纪的全球化

The Distant in the Local: La Quemada and Ancient Globalization in West Mexico, 600-1400

本·尼尔森 Ben A. Nelson

(美国北亚利桑那大学 Northern Arizona University)

背景

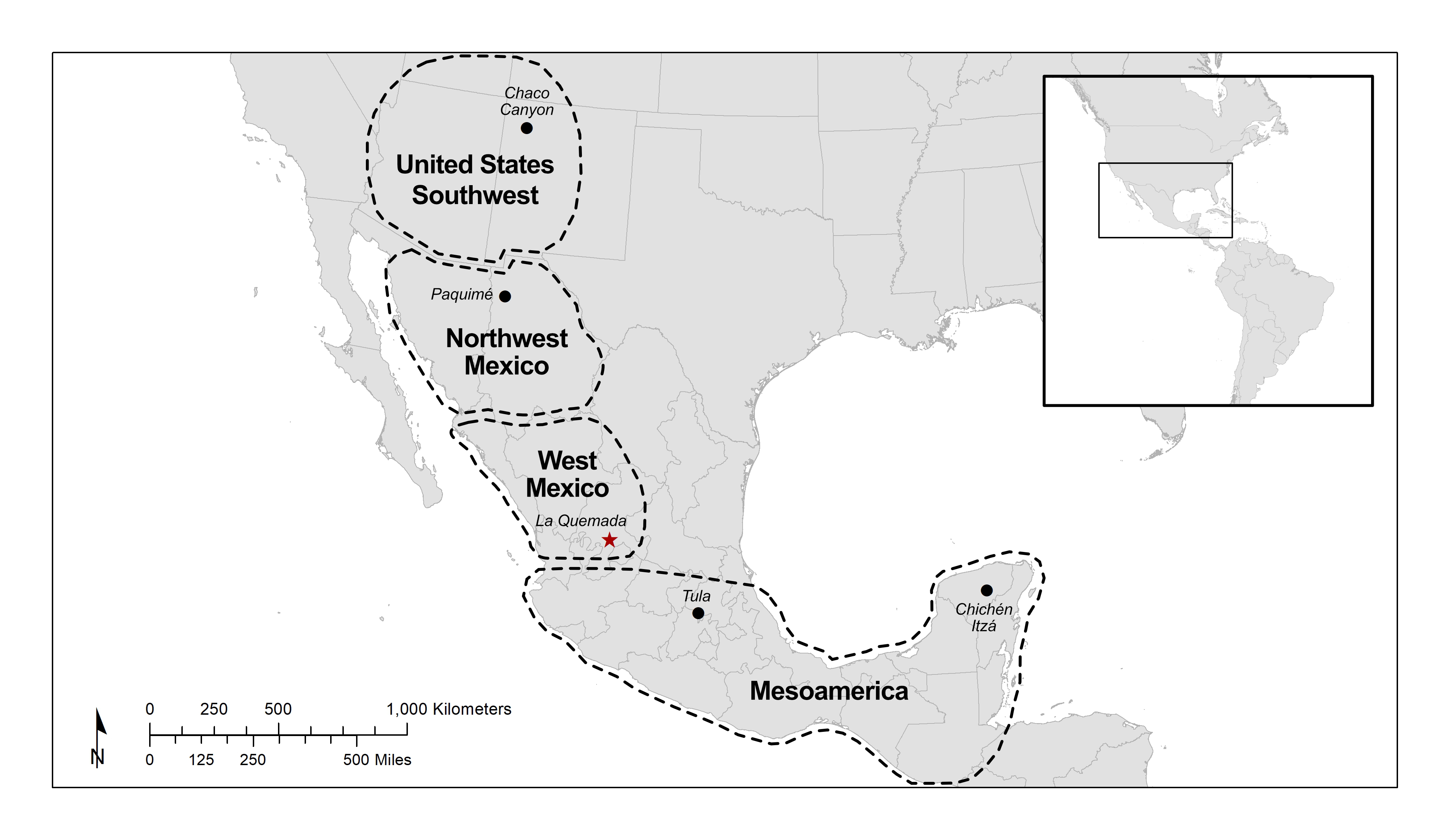

前西班牙殖民时期,中美洲人口城市化与北部地区(包括墨西哥西部、墨西哥西北部和美国西南地区)社会复杂化之间的关联到底如何形成的?这些熟悉而又陌生的东西吸引着我来到墨西哥西部从事研究工作。在这些联系中,最早且影响最为深刻的是玉米农业的引入,约公元前2000年它传播至美国西南地区。几个世纪以来,随着玉米经济的扎根,显示出这种联系的其他标志性物品也出现了,例如:1)绿松石,化学成分与美国新墨西哥州塞里略斯的原料相配,发现于墨西哥尤卡坦半岛一个考古遗址中;2)可可碱–可可作物的咖啡因残留物,原产自中美洲的热带低地,发现于新墨西哥州查科峡谷的陶容器中;3)猩红金刚鹦鹉,源自同一热带地区,发现于墨西哥最北部奇瓦瓦州的帕基梅和美国西南地区的遗址,均被用于祭祀和仪式性埋葬;4)铜料和铜铃,可能是墨西哥西部本地制作,普遍发现于整个美国西南部。这些及其它标志性物大约从公元900年开始大量出现。

新交换网络的出现与墨西哥西部、墨西哥西北部和美国西南部大型区域中心的兴起交织在一起。一些考古学家认为这些中心是城市,另一些则不以为然。无论如何,这些大型聚落从公元600-900年开始出现,比中美洲最早的城市晚了近一千年,代表着中美洲文明向北的扩张。这些遗址中,经远距离获取的物品越来越多,这可以说是一种全球化的表征。当今世界,全球化定义为“生产系统、公司、市场的日益扩大、相互渗透和互相依存……和跨境流动网络”(Martin et al. 2018)。因此,该区域有益于研究城市化和全球化带来的基本问题:为什么会形成中心?为什么它们建立上述联系?受影响地区的生活是如何改变的?交流机制如何随时间而演变?

我与学生及同事在两种地理尺度上(局部和宏观)对这些问题进行了阐释。通过在一个区域中心拉奎玛达开展实地发掘工作,我们实现了以地方视角检验了竞争推动扩张机制假说。竞争将环境驱动因素与政治经济驱动因素对立起来。此项工作由墨西哥政府授权,全称为“拉奎玛达—马尔帕索谷地考古项目”。

在一个遗址点的工作是富有成效的,但它无法解答有关交流的宏观问题。因此,我们结合不同地区的远距离交换数据,构建起宏观区域的视角。数据主要来自档案和文献,以及对长距离物品交换的每个遗址点上资料的梳理。我们按类型和风格、年代和埋藏背景对所有条目归纳编排,数据包括了时间、空间和器物特征,用以评估交换网路的形成及其如何随时间变化的假设。这一国际合作被参与者称为“连接项目”,是“墨西哥西北部文化联系与影响”的简称。

方法和结果

拉奎玛达项目的研究结合了考古学和相关自然科学,以地方视角探讨古代社会文化的变迁。拉奎玛达是一座山顶堡垒和“教长中心”,规模上数倍于同一区域其他聚落。查尔斯·特容波的研究表明,前西班牙殖民时期长达175公里的道路将拉奎玛达和方圆120平方公里区域内200多个附属村落紧密串联起来。这一聚集区以外的地方少有居住,表明与道路相关联的聚落构成了一个古老社群。

我们团队首先绘制了仪式中心的地图,在原有地图中增加了数百个遗迹,构建出聚落所在山体的主要地形轮廓。绘制好的地图上呈现出了大约60个台地。中央纪念性建筑区为砖石结构,包括两个柱廊、13个金字塔或祭坛、巨大的台阶和人行通道、多个下沉式庭院建筑群和一个75米长的球场。其他台地位于保护区外山坡侧面。聚落的形态,加上周围其他较小聚落的聚集,使我们有理由推断,防御是规划建造空间时的一个考虑因素。

该地图提供了一个抽样依据,我们从中选择了一个重要的台地和几个非毗连区域进行发掘。结果表明,18号台地曾被用于居住和仪式行为。在40 × 80 米的台地发现了1座神庙、41 个房间、7 个下沉式天井、3个平台的部分区域、1个球场、1条人行通道和1条楼梯。这些发现可能看起来并不具有革命性,但这是在仪式区外进行的首次考古发掘。考古学家原来甚至不知道台地是用于农业生产还是居住生活。

这次发掘获得了有关建筑空间建构的新信息。几组建筑环绕一个下沉式天井,这些建筑又以一个更大天井为中心,这个大天井中还建有一个长10米的小型球场。我们将这种空间结构称为“俄罗斯套娃式组合”(更好的术语是层级分化)。

我们在不同的台地上发掘了10个垃圾堆积,还在冲积洪泛区发掘了数个探沟以收集环境变化的证据。

为了解气候变化在拉奎玛达的建立和废弃中所扮演的角色,以及是否还可能影响到中美洲扩张,我们借助了地球科学的方法,如孢粉学、地貌学、沉积学和古磁学以分析探沟中的样品。我们寻找拉奎玛达在开发前、使用时和废弃后的环境指标变化。例如,古磁学可能揭示沉积物中铁含量增加,指征侵蚀加剧。这个模式的证实应结合植物考古学有关土地覆被变化的证据。沉积物本身应改变颗粒大小和棱角度。这些研究的主要发现是,没有证据表明环境变化与拉奎玛达的开发有关。如果该地的居住与降雨增加有关,我们应该看到红色曲线向上弯曲,越过最宽的灰色线(代表最大人口)。唯一向上弯曲的红色曲线是乔木花粉,推测其增加可能由人口密度的增加和草地的减少所导致。相反,巨变发生在殖民时期,采矿和农业活动加剧了对该地区森林的破坏。

对人地关系的考察引出了更多问题,我们进行了一些系统研究以期找到答案。我十分感兴趣于开发一个数学模型,用于帮助理解当玉米因干旱而无法种植时,龙舌兰(世纪植物)作为后备资源的作用。龙舌兰可以储存水分以备多年之需,因此可能是这个相对干旱地区生存的关键。模拟结果显示,龙舌兰种植可以消除93%与饥荒相关的迁移需求。

研究人员曾提出远距离交流促进了拉奎玛达的形成,具体来说,菲尔·韦甘德认为该遗址是连接墨西哥中部托特克首府图拉到新墨西哥州查科峡谷“绿松石通道”上的一个中间站。这个假说将我带到了拉奎玛达,因为作为一名受过专业训练的美国西南考古学家,能有机会找到这种联系的切实证据吸引着我。那么绿松石作为原材料和成品在当地有多普遍呢?

我们无法从发掘中找到证据来支持这种中转关系。首先,拉奎玛达年代早于图拉和查科峡谷,二者在公元800年代末-11世纪中叶都有人居住,而拉奎马达的年代则更早,为公元600-800/850年。拉奎玛达仅发现少量绿松石,根据地球化学家艾利森·蒂博多的检测,所发现的不到50颗蓝绿色宝石中只有1/3为绿松石。如果加工成珠子,这种数量的绿松石不会被做成项链。事实上,仅有几件被加工过,呈现了中美洲镶嵌马赛克的特征。因此,通过我们的发掘无法证实拉奎玛达作为从美国西南地区到墨西哥中部这条“绿松石通道”上中间站的假说。

数量极少的绿松石片与阿尔塔维斯塔遗址的发现形成鲜明对比,据查尔斯·凯利和菲尔·韦甘德记录,大约1.7万片绿松石出土于该遗址。因此,拉奎玛达的证据表明,即使是文化上密切相关的同时代聚落,也不一定以同等程度参与到区域间的交流中。

其他遗址常见的遗物在拉奎玛达反而很少见。对400多件黑曜岩石器进行中子活化分析,没有一件来自美国西南部。约翰·米尔豪瑟撰文指出有一件单棱柱石叶是墨西哥中部的黑曜岩。测试结果显示仅4个来自于墨西哥西部,揭示拉奎玛达对该交流网络的有限参与。贝类在发掘中也罕见,特别是贝壳手镯和海螺壳喇叭完全不见,尽管它们在其他区域中心曾被发现过。在拉奎玛达没有发现铜或青铜制品。同样,尼古拉·斯特拉齐奇(Nicola Strazicich)和克里斯蒂安·威尔斯(Christian Wells)借助于岩相学和化学手段分析也未发现任何非本地陶瓷制品。安德里亚·托维宁的博士论文现以文章发表,加深了我们对拉奎玛达陶瓷的理解。到目前为止,我们可以说拉奎玛达似乎在与其他聚落的交换网络中相对不活跃。

在结束对拉奎玛达的讨论前,我必须讲讲它的另一个特殊之处,就是埋有大量人骨,而且大多不是置于墓葬中,而是以展示、捆绑、隐藏或丢弃的方式处理。我的同事彼得·希门尼斯和其他在遗址仪式核心区发掘过的人,发现了超过600多具人骨,都被堆放在立柱大厅地板上等显眼的位置。我们在18号台地的发掘清理出约50具人骨,以头骨和肢骨为主。砍下的人头骨和肢骨在寺庙入口外摆放成一条通道;三组头骨和长骨被捆绑起来挂在神庙内;其他骨骼被置于台阶上。小骨头比如椎骨和指骨则被弃于垃圾坑。只有两个个体被安放在地板下面的暗室内。生物考古学家黛布拉·马丁(Debra Martin)和文图拉·佩雷斯(Ventura Perez)在人骨上发现了两种截然不同的切割痕迹,我们认为其一与敌人相对应,另一种则和祖先崇拜有关。这样的解释意味着存在一定程度的社会暴力,或是以类似战争的方式对人骨进行仪式化处理。

再次重申,为什么说拉奎玛达参与交换网络的程度有限,因为我们在其他遗址发现了数量惊人的远距离交换物品,例如在阿兹特克和米斯特克马赛克版饰中发现了数以万计的绿松石碎片,在奇瓦瓦沙漠的帕基梅发现了数百只金刚鹦鹉和铜铃?为了找出对比悬殊的答案,我们开展了宏观视野下的区域交流研究。

“连接项目”通过收集和分析来自中美洲和美国西南地区数百个前西班牙时期聚落外来物品和符号的数据以解答关于远距离交换的问题。我们的问题涉及宏观区域交流系统的演变。众所周知,阿兹特克时代(公元1345-1519年)已经建立了影响深远的税收和商业体系,符合扩张性外围摄取模式。阿兹特克商业主义是解释早期远距离获取的适当模式,还是其他形式和机制更适合理解宏观区域交换系统的早期发展?墨西哥西北部的参与及其变化是否揭示了起源于中美洲世界体系商品化市场交换的形成时间?

界定交换证据的时空分布有助于考古学家回答此类问题。例如,阿兹特克模式预测了物品和信息向单一市场的流动。又或者,生产中心、独立获取和生产不同的产品间可能存在多种关系。此外,全球化经济中有多大程度的同质性或不平衡性?墨西哥西北部所有区域中心都是远距离互动的中间站吗?从20世纪50年代开始,考古学家首先选择发掘了墨西哥西北部的一些区域中心,发现大量绿松石、贝壳、铜和其他交换物品。然而却没有人借助于交换数据从总体上评估墨西哥西部和西北部中心的共享参与度。

何塞·路易斯·普恩佐(José Luis Punzo)和我共同主持的这个“连结项目”,虽然还处于起步阶段,但已取得了令人兴奋的成果。我们不再笼统的简化中美洲和美国西南部之间的交流,而是考察特定区域和区域中心之间的交流,并且可以看到它具有时间维度。初步研究成果如下:1)交流网络没有涉及该区域的所有聚落点;2)不是所有的区域中心都发现所有种类的远距离交流物品;3)许多情况下,特征交流标志物空间分布差距大; 4) 并非所有墨西哥西部或墨西哥西北部聚落都是交流的中间点。

这是我们一直进行搜集工作的其中部分区域间交流标志物的表格。所列出的均为已知的墨西哥西北部的主要礼仪中心。如上所述,大多数情况下,我们未能证实墨西哥西北部聚落充当过远距离交换网络的中介。事实上引人注目的是,许多中心似乎没有参与远距离交流,或者说如果参与了也只涉及一、两种材料。

讨论与总结

将细致的考古发掘与大量跨区域数据收集相结合,可以为古代全球化研究提供一个解读视角。拉奎玛达在区域交流中有限的参与度表明了墨西哥西部和西北部的参与形式多样,其他遗址的数据也证实了这一观点。事实上,帕基梅、阿尔塔维斯塔和阿马帕等遗址所呈现的参与程度是不同寻常的。可能在一段时间内仅有少数聚落活跃地对远距离物品进行获取,而其余的只是偶尔接受这些物品。

结合这个新视角,解答为何拉奎玛达的参与有限则相对容易。墨西哥西部和西北部的大多数聚落并不参与远距离交换,而且拉奎玛达聚落的使用和废弃都早于宏观区域互动达到高峰的时间。来自类似于拉奎玛达(公元600-800/900年)等大多数早期聚落的数据一致表明特殊商品的获取渠道为远航而非以市场为导向的商业化行为。这些聚落可能仅有一种或几种物品由远距离获得。然而在之后的几个世纪,整体的交换程度提高了。例如,帕奎梅发现的许多金刚鹦鹉、贝壳、铜和青铜文物等(公元 1200~1400 年),阿兹特克和米斯特克绿松石马赛克年代为公元1350~1519年。

虽然我们还未涉及,但是不同时代、不同区域在制度上的变化都印刻在了这里的平台土丘、广场和球场上。

总而言之,上述研究方法能够帮助我们廓清当地与远方之间的关系。这种关系发生于公元前1200年的古代中美洲,在公元前几个世纪早期延伸至墨西哥西部,但直到公元900年后才进入墨西哥西北部和美国西南部,并作为该地区新区域中心而出现。在最早的阶段,扩张是试探性的,不太可能用阿兹特克的商业主义模式来解释。在公元1200年以前,远距离获取物品的实例太少且分散,无法支持有关商业化的争论。即使在公元1200年之后,也尚不清楚外来人口有没有直接干预墨西哥西北和美国西南地区的资源获取,或者说当地人口是否长途跋涉以获取他们所认为的稀有且强大的物品。关于这个不断发展的网络,仍有许多问题有待回答。例如,我们不清楚墨西哥任何的中央势力是否曾干预过这一地区使其与统治制度保持一致。显而易见的是,在所有时间层面,全球化的程度都是不平衡的,总是随当地习俗和实践的变化而变化和调整。

最后,我以一个草图表示原产地和选择标志物出现地的对比。“独立分布”指多种物品在时间和空间上的不同分布,表明非普遍性和几个不同网络的存在。我们注意到区域之间的“非互惠性”,在后古典时代晚期(公元1350年)之前,中美洲缺乏直接的交流证据,而那已经是中美洲物品在北部地区遍及后的五个世纪。绿松石是唯一源自北方的材料,而在公元1350年之前,绿松石物件在中美洲主要的中心仍极为罕见。目前我们所得出的结论是,虽然相互渗透和相互依存的特征从公元900年开始影响北方中心,但直至前西班牙殖民时代晚期才有证据表明共联性,即使如此,许多物品仍存在着空间布局上的差异,意味着墨西哥西北和美国西南地区间多样动态协作。

个人简介

本·尼尔森,亚利桑那州立大学人类演化与社会变迁学院人类学荣休教授,1995-2019年承担教职。研究领域为前西班牙殖民时期墨西哥西北部和美国西南地区的社会政治复杂化和社会连通性。主持了墨西哥拉奎玛达–马尔帕索谷地考古项目,该项目借助于地球科学技术进行环境变化、化学和岩相学研究以评估交流关系,借助于生物考古学考察社会暴力,同时借助于民族考古学了解原住民如何利用地方仪式传统逐步融合。此外,共同负责墨西哥西北部前西班牙时期文化交流影响项目,该项目从宏观区域角度着手远距离交流问题,搜集和分析来自中美洲和美国西南部数百个前西班牙聚落有关外来物品和符号的数据。2004-2009年,担任人类演化与社会变迁学院副院长,2009-2011年担任美国人类学协会考古部主任。撰写和编著了三本书,他的文章曾在《美国人类学家》、《美国古物》、《墨西哥古生物》、《人类生态学》、《人类学考古学杂志》、《美国国家科学院院刊》和《第四纪研究》等期刊上发表。

Background

I was drawn to work in West Mexico by something long recognized and little understood: the formation of prehispanic connections between the urbanized populations of Mesoamerica and the emerging complex societies in regions to the north, including West Mexico, Northwest Mexico and the US Southwest. The most profound and earliest of these connections was the introduction of maize agriculture which reached the US Southwest ca. 2000 BCE. Over many centuries, as maize economies became entrenched, other material markers of such connections appeared, for example: 1) Turquoise, chemically matched to a source in Cerrillos, New Mexico (US), found in an archaeological site in the Yucatan Peninsula (Mexico); 2) theobromine-caffeine residue of the cacao plant, which is native to the tropical lowlands of Mesoamerica, found in ceramic vessels in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (US); 3) scarlet macaws (Psittacidae Ara macao), native to essentially the same tropical regions, found sacrificed and ritually buried, in Paquimé, Chihuahua (extreme northern Mexico, and sites in the US Southwest; 4) copper and bronze bells, probably made in West Mexico, found throughout the US Southwest. These and other markers began to appear in notable frequencies ca. 900 CE.

The emergence of new exchange connections was entwined with the rise of large-scale regional centers in West Mexico, and in Northwest Mexico and the US Southwest (the “NW/SW”). Some archaeologists consider these centers to be cities, while others do not. In any case, these large settlements began to appear ca. 600-900 CE, a millennium later than the earliest cities emerged in Mesoamerica proper, representing an expansion of Mesoamerican civilization to the north. The generally increasing appearance of distantly obtained objects in these sites is a kind of globalization. In today’s world, globalization is defined as “the increasing extension, interpenetration and interdependence of production systems, corporations, markets. . . and networks of flows across national borders” (Martin et al. 2018). The NW/SW is thus a place to investigate the fundamental questions posed by urbanization and globalization: why did centers form, why did they make such connections, how did life change in the affected places, and how did institutions, especially those of exchange, evolve over time?

My students, colleagues, and I have addressed these questions at two geographic scales, the local and the macroregional. We have achieved perspective on the local scale by conducting field work at a single regional center, La Quemada, to test predictions derived from competing ideas about the processes that drove the expansion. The competition pits environmental drivers against political-economic ones. The field work was authorized by the Mexican government under the title of the La Quemada-Malpaso Valley Archaeological Project.

Working at one site was productive, but it could not answer questions about the bigger picture of exchange. So, we began to build a macroregional perspective by combining data on long-distance exchange from many different regions. This work is primarily archival and bibliographic, mining data site-by-site for occurrences of long-distance exchange items. We tabulate the items in overarching typologies of form and style, chronology, and contexts of deposition. The data constitute a grid of time, space, and artifact characteristics against which to evaluate hypotheses about the form of network(s) and how it or they changed over time. This international collaboration is known to its participants as the Connections Project, short for Connections and Impacts of Northwest Mexican Cultures.

Methods and Results

Studies at La Quemada have used a range of methods from archaeology and related sciences to explore ancient socioenvironmental change at the local level. La Quemada is a hilltop fortress and a “primate center,” many times larger than the other settlements in its orbit. Charles Trombold has shown that 175 km of prehispanic roads connect La Quemada to over 200 tightly clustered, subordinate villages in a 120 km2 area. The areas beyond this cluster were lightly occupied, suggesting that the road-related settlements constituted an ancient community.

Our team first mapped the ceremonial center, adding hundreds of features to an existing map that showed the major topographic contours of the hill. The mapping revealed some 60 terraces. Those in the monumental central precinct were masonry structures, including two colonnaded halls, 13 pyramids or altars, massive staircases and causeways, numerous sunken patio complexes, and a 75 m ball court. Other terraces are located on the flanks of the hill outside that protected zone. The configuration of the settlement, plus the clustering of other smaller, settlements around it, makes it reasonable to infer that defense was a consideration in creating built space.

The map provided a sampling framework from which we selected one major terrace and several non-contiguous areas for excavation. Excavation showed that Terrace 18, at least, was occupied and used for both residential and ceremonial purposes. The 40 x 80 m terrace included one temple, 41 other rooms, seven sunken patios, parts of three platforms, a ball court, a causeway, and a staircase. These findings might not seem revolutionary, but this excavation was the first to be conducted outside the ceremonial precinct. Archaeologists did not even know whether the terraces were agricultural or residential.

The excavations yielded new information about the spatial configurations of built space. Several groups of structures surrounded sunken patios; those groups together surrounded a larger patio, which contains a small ball court with a 10 m playing surface. The arrangement is one that we refer to in the United States as a Russian-doll arrangement (a better term is fractal).

We also excavated 10 trash middens associated with different terraces, and we dug offsite trenches in the alluvial floodplain to collect evidence of environmental change.

To see whether climate change played a role in the founding and abandonment of La Quemada, and therefore possibly in the Mesoamerican expansion, we used earth-science methods such as palynology, geomorphology, sedimentology, and paleomagnetism to analyze the samples from the offsite trenches. We looked for changes in environmental indicators belonging to the periods before, during, and after the major occupation of La Quemada. For example, paleomagnetism might reveal a increase in the iron content of sediments, indicating increased erosion. That pattern should be corroborated by botanical evidence of changing land cover. The sediments themselves should change in particle size and angularity. The main finding of these studies was that no evidence of environmental change could be detected in association with the main occupation of La Quemada. If the occupation were associated with improved rainfall, we should see upward inflections in the red lines where they cross the widest gray line (representing greatest human population). The only red lines that do inflect upward are arboreal pollen, which may have increased because of a decrease in grasses, and human population, which represents the main occupation itself. Major changes were seen instead in the Colonial period, when mining and agricultural activities led to deforestation in the region.

Investigating human-environmental relationships led to further questions, which we conducted several systematic studies to answer. One that particularly interested me was the development of a mathematical model to help understand the role of agave (century plant) as a backup resource when maize failed due to drought. Because agave can store water to feed itself for years, it might have been a key to survival in this relatively arid region. A simulation shows that agave cultivation could have eliminated the need for an astonishing 93% of famine-related migrations.

Researchers had suggested that long-distance exchange was a stimulus to the formation of La Quemada, specifically, Phil Weigand argued that the site was a station on a “turquoise trail” connecting Tula, the Toltec capital in central Mexico to Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, where the great quantities of turquoise have been found. This suggestion brought me to La Quemada because, trained as a US Southwestern archaeologist, I was intrigued by the chance to find tangible evidence of such a connection. Just how common was turquoise as a raw material and as finished objects in the local setting?

We were unable to confirm the intermediary relationship with evidence from excavation. For one thing, La Quemada turns out to be earlier than Tula and Chaco Canyon – they both are occupied from the late 800s till mid 1100s CE, whereas La Quemada is earlier, 600-800/850 CE. La Quemada also turns out to have very little turquoise. We found fewer than 50 blue-green stones, only a third of which were turquoise according to geochemist Alyson Thibodeau. If worked into beads, this quantity of turquoise would not make a necklace. In fact, only a few pieces were worked, notably including a tessera characteristic of Mesoamerican mosaics. Thus, our excavation data did not confirm the idea of La Quemada as an outpost on a turquoise trail from the US Southwest to Central Mexico.

The small number of turquoise pieces contrasts with the high frequencies from Alta Vista; about 17,000 were documented by J. Charles Kelley and Phil Weigand. The La Quemada data thus show that even contemporary sites that were quite closely related culturally, did not necessarily have the same degree of participation in interregional exchange.

Items common at other sites were rare at La Quemada. Of over 400 pieces of obsidian submitted for neutron activation analysis, none were from the US Southwest. John Millhauser’s thesis notes a single prismatic blade of Central Mexican obsidian. Four West Mexican sources are represented in the analysis, revealing La Quemada’s limited participation in that network. Shell was also infrequent in the excavation samples, and notably, shell bracelets and conch-shell trumpets were not recovered, although they are found in other regional centers. No copper or bronze items have been found at La Quemada. Likewise, petrographic and chemical analyses by Nicola Strazicich and Christian Wells did not identify any non-local ceramic wares. Andrea Torvinen’s dissertation, now being published as articles, deepens our understanding La Quemada ceramics. As of now we may say that in a range of materials, La Quemada appears to have been relatively inactive in the exchange networks that existed among other sites.

Before leaving La Quemada, I must describe one of its hallmarks, the massive deposits of human bones, which were mostly not burials, but displays, bundles, caches or discards. My colleagues Peter Jiménez and others who have worked in the monumental core of the site have found over 600 skeletal individuals piled in prominent places such as on the floor of the Hall of Columns. Our excavations on Terrace 18 revealed about 50 individuals, mainly in the form of skulls and long bones. Suspended human skulls and long bones formed a passageway outside the entrance to the temple; three groups of skulls and long bones were hung in bundles inside the temple; other sets were placed on stairways. Small bones such as vertebrae and phalanges were deposited in the trash middens. Only two individuals were placed in chambers beneath the floors. Bioarchaeologists Debra Martin and Ventura Perez identified two distinct patterns of cut marks on the human bones, which we believe correspond to enemies on the one hand and revered ancestors on the other. This interpretation implies a level of social violence, or else ritualized processing of human bone in ways that look warlike.

Once again, why was La Quemada’s participation in exchange networks limited, while other sites had phenomenal quantities of distantly obtained items; for example, the tens of thousands of turquoise pieces in Aztec and Mixtec mosaic plaques, or the hundreds of macaws and copper bells at Paquimé in the Chihuahuan desert? To find out, we have initiated the macroregional exchange study.

The Connections Project has been attacking the question of long-distance exchange by gathering and analyzing data about exotic objects and symbols from hundreds of prehispanic settlements in Mesoamerica and the US Southwest. Our questions concern the evolution of macroregional exchange relations. It is well known that by Aztec times (1345-1519 CE), far-reaching systems of taxation and commerce were in place, conforming to a model of expansionary peripheral extraction. Is Aztec mercantilism an appropriate model for distant acquisition in earlier periods, or are other forms and mechanisms more apt to explain the early development of the macroregional exchange system? Do changes in northwest Mexican participation reveal a time when commercialized market exchange originated in the world-system of Mesoamerica?

Defining the spatial and temporal distribution of evidence for exchange should help archaeologists answer such general questions. For example, the Aztec model predicts a single set of relations coordinating flows of goods and information into a single marketplace. Alternatively, there could have been different sets of relations among centers of production and independent acquisition and production of different goods. Also, how homogeneous or uneven was participation in the globalizing economy? Were all northwest Mexican regional centers intermediaries in the distant interactions? Some of the first northwest Mexican regional centers that archaeologists chose to excavate, beginning in the 1950s, abounded in turquoise, shell, copper, and other exchange items. Yet, no one has looked at the exchange data in the aggregate to assess the extent of shared participation by West and Northwest Mexican centers.

This project, of which José Luis Punzo and I are co-directors, is still in its early stages but already is yielding exciting results. We no longer see exchange as simply between Mesoamerica and the US Southwest, but among specific regions and regional centers, and we can see it with a time dimension. Examples of our initial major findings are: 1) the networks did not involve all sites in the region; during any given time period, only certain sites were involved; 2) not all regional centers contain all kinds of objects; 3) in many instances there were very large spatial gaps in the occurrence of specific interaction markers; 4) not all West Mexican or northwest Mexican sites were intermediaries.

Here is a partial tabulation of a set of markers of interregional interaction that we have been tabulating. All sites listed are major ceremonial centers in NW Mexico. As noted, the expectation that groups in NW Mexico served as intermediaries in a long-distance exchange system is not borne out in most cases. Indeed, what seems striking is that many centers appear not to be participating in long-distance exchange, or if they are, only in one or two materials.

Discussion and Conclusion

Combining intensive site study with extensive interregional data collection permits a perspective on the problem of ancient globalization. La Quemada’s limited participation in interregional exchange suggests variable West Mexican and northwest Mexican participation, and additional data from other sites confirms this. Indeed, participation at the level manifested in sites such as Paquimé, Alta Vista, and Amapa is unusual. It may be that at any one time, only a select few sites were highly active in acquiring distant objects, and the rest were only occasional recipients of these valued goods.

Incorporating this new perspective, the answer to why La Quemada’s participation was limited is relatively simple. Most sites in West Mexico and northwest Mexico were not highly involved in long-distance exchange, and moreover, La Quemada was occupied and abandoned before the level of macroregional exchange reached its peak. The data from most early sites like La Quemada (600-800/900 CE) are consistent with a pattern of voyaging to obtain special goods rather than market-directed, commercialized behavior. Such sites may have one or a few items that mark distant acquisition. In later centuries, however, the overall level of exchange increased. For example, Paquimé with its many macaws, shell items, copper and bronze artifacts, etc., dates to 1200-1400 CE, the Aztec and Mixtec turquoise mosaics are from 1350-1519 CE.

Although we have not touched upon it, platform mounds, plazas, ball courts mark other institutional change in the times and regions of interest here.

In sum, our research strategy allows us to characterize the distant in the local. Such presence existed in ancient Mesoamerica proper from 1200 BCE, extending to West Mexico by the early centuries BCE, but not until after 900 CE into Northwest Mexico, and the US Southwest as new sets of regional centers arise. In its earliest phases, this extension is somewhat tentative, and it is unlikely to be explained by an Aztec-like model of mercantilism. Before about 1200 CE, the instances of distantly obtained objects are too few and scattered to support a contention of commercialization. Even after 1200 CE, it is unclear whether foreigners were directly intervening in the NW/SW to acquire resources, or the NW/SW peoples were traveling great distances to acquire what from their perspective must have been rare, powerful objects. A great many questions remain to be answered about this evolving network. For example, it is not clear whether any central Mexican powers ever intervened in this region and brought it into alignment with their systems of dominance. What is clear is that at all time levels, the degree of globalization was uneven, always changing and mediated by local custom and practice.

I conclude with a sketch representing the occurrence of selected markers of interaction in comparison to their source areas. “Separate distributions” means different distributions in time and space for several items, suggesting non-pervasiveness and the existence of several distinct networks. We note “non-reciprocity” between regions, a lack of evidence for direct exchange in Mesoamerica prior to the Late Postclassic (ca. 1350 CE), almost five centuries after Mesoamerican items become common in the north. Turquoise is the only material that comes from northern sources, and turquoise artifacts are vanishingly rare in major Mesoamerican centers predating 1350 CE. For now, we conclude that although interpenetration and interdependence began to affect northern centers ca. 900 CE, there is little evidence for mutuality until late in prehispanic times, and even then there were large spatial gaps in the occurrence of many items, implying variable integration of the areas in the NW/SW.

Biographic Sketch

Ben Nelson is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, School of Human Evolution & Social Change, Arizona State University, where he taught from 1995 till 2019. He is interested in cycles of sociopolitical complexity and connectivity in the prehispanic societies northwestern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest. He directs the La Quemada-Malpaso Valley Archaeological project in Mexico, which has used techniques from the earth sciences to explore environmental change, chemistry and petrography to evaluate exchange relationships, bioarchaeology to evaluate social violence, and ethnoarchaeology to understand the ways in which regional ritual traditions integrate indigenous populations. He also is co-director of the Connections and Impacts of Prehispanic North and West Mexican Cultures project, which addresses the question of long-distance exchange from a macro-regional perspective, gathering and analyzing data about exotic objects and symbols from hundreds of prehispanic settlements in Mesoamerica and the US Southwest. He served as Associate Director of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change from 2004-09, and as President of the Archaeology Division of the American Anthropological Association from 2009-11. He is author or editor of three books; his articles have appeared in journals such as American Anthropologist, American Antiquity, Arqueología Mexicana, Human Ecology, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (US), and Quaternary Research.