人类协作演变的考古学研究

The Evolution of Human Co-operation

查尔斯·斯坦尼斯 Charles Stanish

(美国南佛罗里达大学 University of South Florida)

在超过50,000年的时间里,现代人生活在狩猎、采食、集食的小规模社群中。 这种生活方式是我们物种在演化历史上发展出的最成功的适应方式。语言的发生和人类独具的象征性行为使我们这一物种在全新世早期就统治了世界上绝大多数宜居的陆地生境。在人类历史的关键时期——大约11,000年前的东半球——几个地方的一些人们在生活的地方建起了纪念物。他们在架高的平台上用木头或石头建造纪念物,壁内还有精美的浮雕。 这些地方是游牧或半游牧民族时段性集会的“特殊场所”,暂时还没有更好的术语来称呼。

诸如安纳托利亚的哥贝克力土丘和北美的贫穷角之类的遗址,是具有代表性的 “复杂的非国家社会”起源的考古学遗存。这些社会被认为是能够成功进行协作的社群,尤其能够在这些特殊的场所建造和维护纪念性建筑。我们可以合理推断,如果这些团体有能力组织大量的人来建造这样的纪念碑,那么他们社会结构的复杂程度也将远远超过更新世晚期典型的小规模游团。

为了了解世界上各个地区的社会复杂化的历程,我们必须摒弃传统的“文化进化论”的概念,转而使用“协作的演进”这一看法。这一智识转变的核心是对“理性人理论”的认识,这是经济博弈论和传统文化进化论的基础,不足以解释富有智慧的、具有适应性的主体之间存在的持续性合作行为,尤其是他们生活在没有社会高压或政治性组织的小规模社群中。相反,协作的演进必须被理解为一种集体决策问题——让社群中的人们随着时间推移为达成共同的目标而进行协作,脱离团队事关个人的切身利益。在我看来,在历史学研究中,进化博弈论最有效的解决了这种集体决策问题。我认为问题的关键在于:没有货币,没有市场,没有政治力量,没有官僚机构,没有社会阶层分化和其他高压机制的小规模社群是如何随着时间的推移,制定出可持续的经济和社会协作常规和准则的。这便是社会复杂化在全新世中发生的背景。

我坚持认为,这种协作是通过经济的“仪式化”来实现的。这些社群设立常规、仪式和禁忌来组织经济。这一结论是基于丰富的对全球各地非国家社群的民族学观察数据以及考古材料的研究得出的。这种精巧的经济行为准则蕴藏在丰富的仪式实践中,对这些“原始人类”来说并不是奇异独特的习俗,而是能够在公然的、或者微妙的政治高压缺席的情况下组织社会的巧妙手段。换句话说,在非国家社会中,集体决策问题是通过仪式化特定行为,并提供维持协作所必需奖惩来实现的。协作的社群中成员之间的经济关系在多大程度上被仪式化了,这是在全新世的竞争环境中成功的关键。

可用进化博弈论和相关理论中的概念来理解这一过程。我提出了 “人类学博弈论”的概念,以区别于“进化论的”和基于理性人原则的、或经济学的博弈论。人类学博弈论使我们能够理解小规模社群行为是一种社会理性——也可以理解为“非理性、基于既定社会准则的行为”——与经济理性相反。这是人类社会互动中所遵循的主要原则。

从考古学的时间尺度来看,我们看到的是一种文化传播过程。在这种过程中,最能够促进社群协作的方法会被选择出来,或者被他人模仿。我将这一过程称为“战略”选择,将其与社群的或其他多级的选择区分开来。然后,这种成功的战略以文化形式在代际间传播,但缺乏正式的强制执行机制,直到国家社会的出现和与此同时的强制性社会机制的发展。

在过去的两代考古人的研究中,我们已经发现了世界上许多个地区最早的复杂社会。很多案例都能够说明人类协作的演进过程。我在这里使用来自秘鲁南海岸,公元前800年–公元前200年左右的帕拉卡斯人的例子。

2012年,在安第斯山脉提提卡卡盆地进行了30年的研究之后,我和同事亨利·坦塔莱安在秘鲁南海岸的钦查河谷开始了一项长期的考古研究计划。得益于先前考古学家的工作和我们自己的新数据,我们得以整理了全面的,始于几千年前的河谷史前史。其中一个重要的时期被称为帕拉卡斯,这个社会在大约公元前400年发展到顶峰,并在公元200年终结并转变为另一种文化。这是这个地区最初的复杂社会和文明起源。我们的工作数据为理论学者们模拟在世上罕有的文明独立起源的地区之一发生的复杂化过程提供了又一具体案例。

我们在河谷中发现了大量帕拉卡斯文化遗存,从大型的金字塔,到散布在区域内的小村庄。我们还发现,在河谷附近极度干旱的草原地区有帕拉卡斯人留下的线性地画。类似于著名的纳斯卡地画,但要更早几个世纪,钦察地画是刻画在沙漠上,并有小块粗石勾勒。我们还发现地画共有五组,都集中在大草原边缘的五个主要帕拉卡斯文化遗址所在地,地画之间还存在许多小的建筑物。研究表明,许多小建筑物和地画都朝向夏至日的日落方向。我们团队和秘鲁各处其他的早先的工作明确地表明,前哥伦布时期安第斯地区的人们使用二至日来标记重大事件。

我们认为,这些地点是具有仪式重要性的社会事件的终结之地,这些事件发生的时间可能是由冬至日或其他天文学现象来标记的。此类仪式事件正是非常符合协作理论原则的那些“策略”。我们选择深入研究塞罗•德尔•蒂尔遗址,根据我们的理论,探究其在帕拉卡斯文化中的重要性。该遗址是一个有三层的大型土堆平台。底层最大尺寸约为50×120 m,是河谷地区典型的帕拉卡斯建筑样式。每层还有一个边长约12米的下沉式天井。

坦塔莱安和他的团队发掘了这其中的一个天井,出土了大量人工制品,包括织物、食物、陶器、有装饰的葫芦、石器、藤编物、其他杂物和殉人。尽管我们没有发现常驻人口的证据,但找到了承装玉米酒的大型陶器。遗址还有大量的陶制器皿用于献祭,还有证据表明在仪式活动结束后大量的酒被倾倒进了天井里。塞罗•德尔•蒂尔无疑是一个重要宴飨场所的经典考古例证。

人类史前和历史时期最早的协作社群的本质是复杂社会起源问题中还未被解决的主要问题。我们用塞罗•德尔•蒂尔遗址的数据来检验以下假设:人们是否是从“小规模”的,本地社群中宴飨活动开始,然后随着他们本身扩展成更大的政治组织,宴飨活动也吸纳了更远的社群?又或者,是最早成功的社群在大区域内成功和更远距离的自治社群建立了联系?来自亚利桑那州立大学的凯里•努森分析了在天井发现的39个有机遗存的锶含量,包括人类遗存在内的各种有机体中87Sr / 86Sr的比率都可以说明他们的地理来源。我们发现天井中遗物的来源非常广泛,遍布在安第斯山脉中南部周围。

该研究表明,秘鲁南海岸最早的复杂社会汇集了大量的人和物,形成于约公元前400年。至少在帕拉卡斯社会中,建设文明的最佳方法是在初期广泛建立同盟,然后在随后的数百年里进行扩张。形成鲜明对比的另一种策略是专注发展本地社群,并随着时间逐渐成长。

秘鲁南部的研究数据表明,仪式与社会复杂化过程交织在一起。国家起源的途径必然包括具有高度互动性的仪式,这些仪式能以社会、政治、经济和文化原因将跨区域的人群聚集在一起。我们假设在演进初期存在许多相互竞争的社群。随着时间的流逝,我们观察到遗址数量减少,但纪念性建筑的规模却增大了。这表现的就是区域合并的过程,在一些地方,这一过程导致了真正的,国家起源的质的飞跃。

个人简历

查尔斯·斯坦尼斯是南加州大学文化与环境高级研究所的执行主任。他曾在加州大学洛杉矶分校任教人类学,并担任扣岑考古研究所所长达20余年。他在秘鲁、玻利维亚和智利开展过广泛的工作,研究这些地区的史前社会。查尔斯毕业于宾夕法尼亚州立大学,获得学士学位,之后在芝加哥大学获得博士学位。他理论方面的研究集中在贸易、战争、仪式和劳动力组织在人类协作的演进和社会复杂化中所扮演的角色。查尔斯的主要著作包括《人类协作的演进》(2017年,剑桥)、《古代提提卡卡: 秘鲁南部和玻利维亚北部的社会复杂化》(2003年,伯克利) 、《古代安第斯山脉中的仪式和朝圣》(与B· Bauer合著,2001年,得克萨斯)和《古代安第斯政治经济》(1992年,得克萨斯) 。他还与一个可持续发展组织合作,通过小额贷款、组织直接赠款和旅游基础设施建设来保护全球文化遗产。他曾是敦巴顿橡树园研究图书馆的高级研究员,现任美国文理科学院院士院士、美国国家科学院院士。

For well over 50,000 years, modern humans lived in small groups of hunter-gatherer-forager societies. This way of life was the most successful adaptation in the history of our species. The evolution of language and the unique human capacity for symbolizing behavior allowed our species to dominate virtually all of the favorable continental habitats in the world by the early Holocene. At this critical juncture in the human career– around 11,000 years ago in the Eastern Hemisphere— a few peoples in a few places built monuments on the landscape. The monuments were built out of wood and stone. They held elaborate carvings inside walls that were built on elevated platforms. These locations were, for lack of a better term, “special places” where nomadic and seminomadic groups congregated for periods of time.

Sites such as Göbekli Tepe in Anatolia and Poverty Point in North America represent the archaeological signature of the development of “complex stateless societies.” These societies are defined as small groups with the capacity to create successful co-operative social organizations that can, among other things, construct and maintain the monumental structures in these special places. We can reasonably infer that if these groups had the capacity to organize large numbers of people to construct such monuments, they also had a complex social structure well beyond that of the small, nomadic band typical of the Late Pleistocene.

In order to understand the development of these first complex societies in any region of the world, we have to move away from the standard concept of “cultural evolution” to one of the “evolution of co-operation.” Central to this intellectual shift is the recognition that rational actor theory, the basis of economic game theory and traditional cultural evolutionary theory, is inadequate to explain sustained co-operation among intelligent, adaptive agents, particularly people living in small groups without coercive social or political institutions. Rather, the evolution of co-operation must be understood as a type of collective action problem – getting people in your group to co-operate over time for a common set of goals even if defecting from the group is in your immediate self-interest. This collective action problem in the historical sciences, in my view, has been most effectively dealt with using evolutionary game theory. The major question in my view is this: how do people living in small groups without money, markets, policing powers, bureaucracies, social classes, and other coercive mechanisms develop norms and rules of economic and social co-operation that are sustainable over time? This is, after all, precisely the context in which complex societies evolved in the Holocene.

I maintain that such co-operation is achieved by “ritualizing” the economy. These groups constructed norms, rituals, and taboos to organize their economy. These conclusions are based on a rich set of ethnographic data on stateless societies around the globe and on observations of the archaeological record. Far from being quaint and exotic customs of “primitive peoples,” the elaborate rules of economic behavior, encoded in rich ritual practices, are ingenious means of organizing a society where political coercion backed by overt or subtle force is absent. In other words, in stateless societies, the collective action problem is dealt with by ritualizing certain behaviors and providing the rewards and punishments necessary to maintain co-operation. The degree to which economic relationships between members of the co-operative group were ritualized to support that co-operation is the key to success in the competitive environment of the Holocene.

This process can be understood using concepts from evolutionary game theory and allied disciplines. I propose the concept of “anthropological game theory” to differentiate it from “evolutionary” and rational actor-based or economic game theory. Anthropological game theory allows us to understand small-group behavior where social rationality – also known as “irrational, prosocial behavior” – as opposed to economic rationality, is the dominant principle of human social interaction.

From an archaeological time scale perspective, we see a cultural transmission process in which the best strategies that promote group co-operation will be selected for, or imitated by others. I refer to this process as “strategy” selection, differentiating it from group or other kinds of multilevel selection. These successful strategies are then culturally transmitted through generations in societies without formal mechanisms of enforcement until the emergence of state societies and the simultaneous development of coercive social mechanisms.

Archaeological research over the last two generations have uncovered many of the world’s first complex societies in any region of the world. Many of these case studies illustrate this process of the evolution of human co-operation. The case study I use here comes from the south coast of Peru among the Paracas peoples circa 800-200 BCE.

In 2012, after 30 years of research in the Titicaca Basin in the high Andes, my colleague Henry Tantaleán and I started a long term archaeological research program in the valley of Chincha in the south coast of Peru. Thanks to work by previous archaeologists and our own new data, we have been able to piece together a comprehensive prehistory of the valley beginning several millennia ago. One significant period is known as Paracas, a society that peaked around 400 BCE and ultimately transformed into a different culture by AD 200. This is the time when the first complex societies developed in the region, the origin of civilization in this part of the ancient world. The data from our work provides yet another detailed case study for theorists to model the evolution of complexity in one of the rare places in the world where civilizations independently developed.

We documented a massive Paracas presence in the valley, ranging from large pyramid structures to modest villages scattered over the landscape. We also discovered that the Paracas peoples built linear geoglyphs across the hyper-arid pampa lands above the valley. Like the famous lines of Nazca but several centuries earlier, the Chincha lines were etched into the desert and lined with small field stones. We also discovered the there were five sets of lines and that these sets all concentrated on the five major Paracas sites at the edge of the pampa. We also found many small structures built in between the lines. Our research indicated that a number of these small structures and many of the lines pointed to the June solstice sunset. Previous work by our team and others throughout Peru unequivocally indicates that the pre-Columbian peoples of the Andes used the solstices to mark important events.

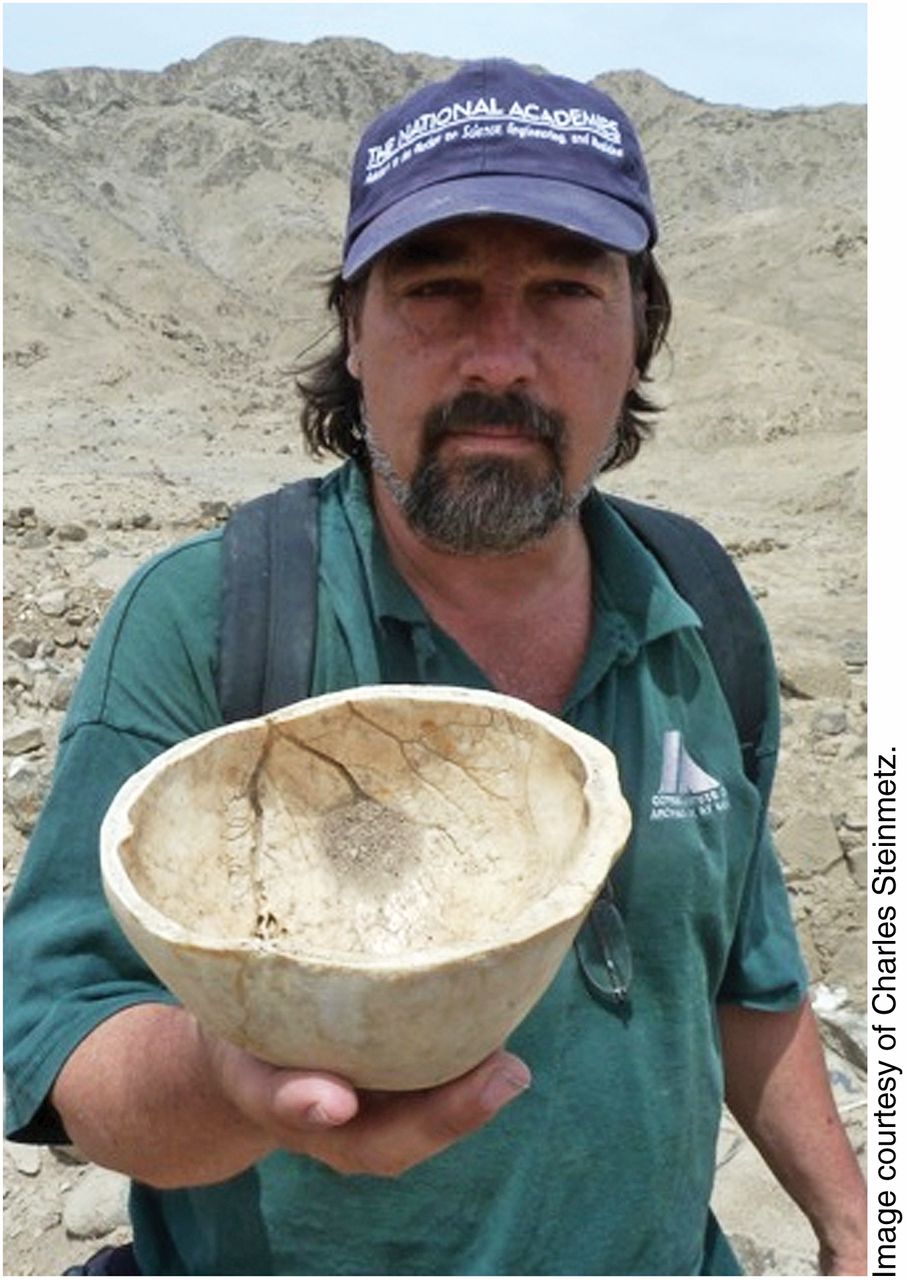

We concluded that these sites were the end-points of ritually-significant social events that were timed by the winter solstices and possibly other astronomical phenomena. These ritual events were strategies that fit quite well with the principles of the co-operation theory. We chose to intensively study one end-point site, called Cerro del Gentil, to assess its significance in Paracas culture and in light of our theoretical ideas. The site is a large platform mound with three levels. The base level measures 50 × 120 m at its maximum and conforms to a classic Paracas architectural pattern in the valley. There is a sunken patio in each level measuring around 12 meters on a side.

Excavations by Tantaleán and his team in one of these patios yielded a rich trove of artifacts deposited in one of the sunken patios. The artifacts recovered included textiles, food stuffs, pottery, decorated gourds, stone objects, cane, miscellaneous objects, and human offerings. We found large pottery vessels that held maize beer. We found lots of evidence of food preparation as well, though we did not find a resident population. The site contained large numbers of pottery serving vessels and evidence of termination rituals involving liquid libations poured into the patio. Cerro del Gentil, in fact, was a classic archaeological example of a very significant feasting place.

One of the unanswered questions in the origin of complex societies centers on the nature of the earliest co-operative groups in human history and prehistory. We used the Cerro del Gentil data to test the following hypotheses: Did people start out “small”, feasting within their local group and then expanding to incorporate more distant groups as they evolved into large polities? Or, did the earliest successful groups develop contacts with distant autonomous groups around a large region? Our colleague Kelly Knudson from Arizona State analyzed the strontium ratios in 39 organic objects found in the patios as offerings. The ratio of 87Sr/86Sr in any organic object, including humans, tells us from what geographical zone that object is from. We discovered that objects in the patio were from a very broad range of ecozones around the south central Andes.

This case study demonstrates that earliest successful complex societies in the south coast of Peru ca. 400 BCE involved a wide catchment of people and objects. At least in Paracas society, the optimal strategy of civilization-building involved creating widespread alliances early on and then expanding on this model over centuries. This contrasts with a strategy in which people focused on their local group and then grew incrementally over time.

The data from southern Peru demonstrate how ritual was intertwined with the evolution of complex society. Strategies of state development necessarily included highly interactive ceremonies that brought together many different peoples from across the region for social, political, economic and cultural reasons. We hypothesize a landscape in which there were many competing groups at the beginning of this process. Over time, we see that the number of sites decreases but the size of the monumental increases. This represents a process of regional consolidation of political centers which, in a few places around the world, made the evolutionary leap to fully coercive state societies.

Biographical Sketch

Charles Stanish is Executive Director of the Institute for the Advanced Study of Culture and the Environment at USF. He was a professor of Anthropology and director of the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA for 20 years. He has worked extensively in Peru, Bolivia, and Chile, conducting archaeological research on the prehistoric societies of the region. He earned his BA from Pennsylvania State and his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. His theoretical work focuses on the roles that trade, war, ritual, and labor organization play in the evolution of human cooperation and complex societies. His primary books include The Evolution of Human Co-operation (2017-Cambridge), Ancient Titicaca: The Evolution of Complex Society in Southern Peru and Northern Bolivia (2003-Berkeley), Ritual and Pilgrimage in the Ancient Andes (with B. Bauer, 2001-Texas) and Ancient Andean Political Economy (1992-Texas). He also works with a sustainable development group to preserve global cultural heritage through a combination of micro-lending, direct community grants, and tourist infrastructure development. He was a Senior Fellow at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States.