奥梅克文化:中美洲最古老文明的研究

Researching the Olmec, Mesoamerica’s oldest civilization

安·赛弗斯 Ann Cyphers

(墨西哥国立自治大学 National Autonomous University of Mexico)

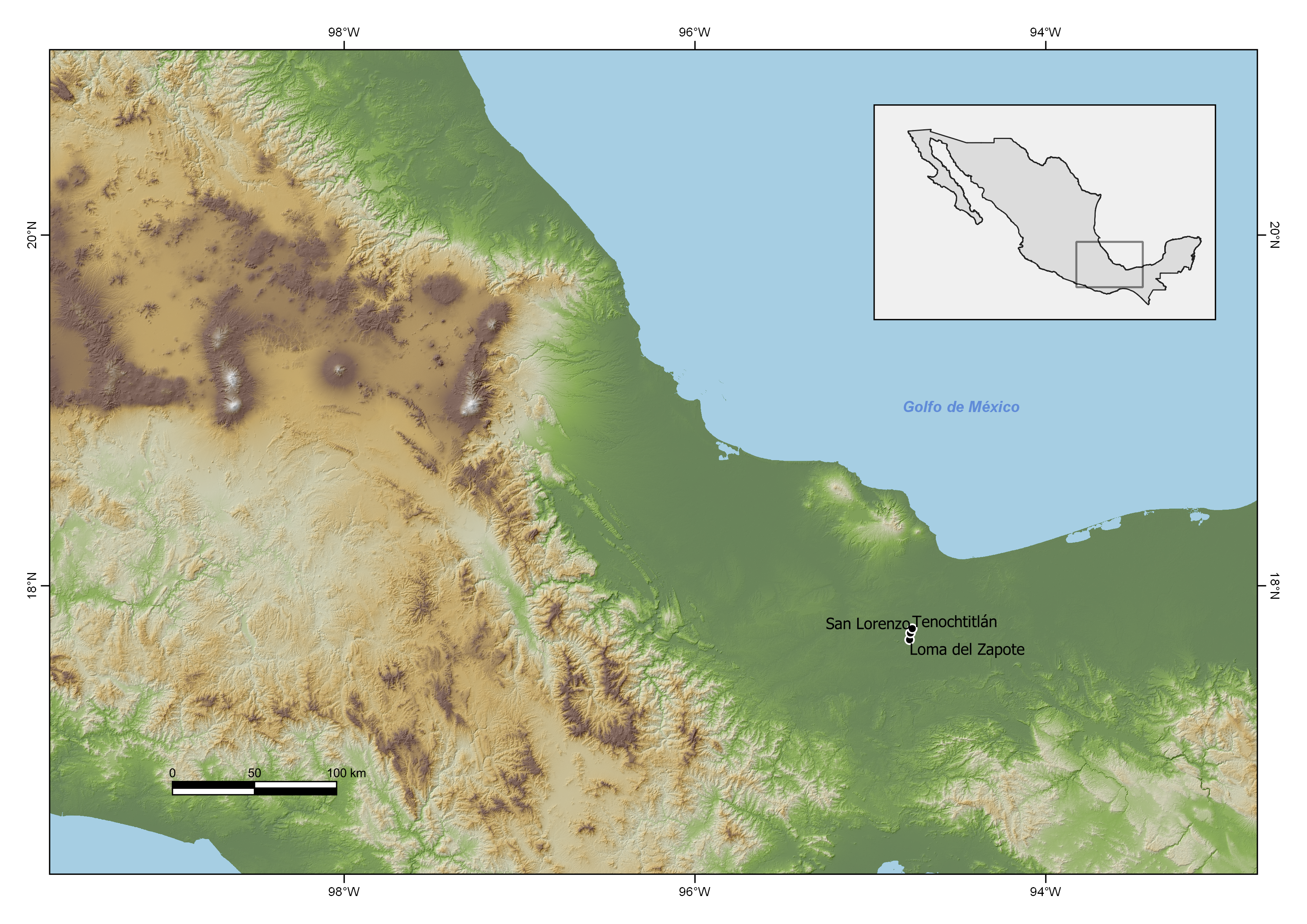

奥尔梅克文化起源于大约4000年前的墨西哥南部湾岸湿热带地区。它的出现和早期发展发生在公元前1800年至800年之间的韦拉克鲁斯州圣洛伦佐。在其最辉煌的时期,它管理着穿越沿海平原和湿地的区域通信和运输系统,并建立了独特的地缘政治领地以及区域和长途贸易体系。其著名的纪念性石雕艺术的主题主要集中于统治者,政府和宇宙学。奥尔梅克的这些纪念性石雕作品是既存的社会和政治能力的物质化象征,奥尔梅克纪念石雕是一种既存的社会和政治能力的具体化,这种社会和政治能力是为了巩固专门的生产和组织大量的劳动力,以便从60公里外的产地远距离运输这些重达数吨的石头。。它还显示了由宗教支持并由世袭统治者领导的分化为不同阶层的社会组织形态和集中政治制度。与水和冥界有关的超自然观念构成了具有王室血统成员的特有的意识形态。

1945年,马修·斯特林和他的妻子马里恩在关于其古老性,以及它与玛雅之间可能存在的继承和发展关系的激烈辩论中发现了圣洛伦索。该遗址的下一个重大调查是由迈克尔·科指导的,他建立了圣洛伦佐的古代时期,进行了第一次地层发掘,在现有的艺术品中增加了许多雕塑并研究了现代环境。圣洛伦索·特诺奇提特兰考古项目的研究始于1990年,当时奥尔梅克地区的考古工作长期处于停滞状态。其明确的目的是用多学科方法研究奥尔梅克文明生活和文化发展中相对未知的方面。

地貌学研究提供了有关奥尔梅克时代存在的景观的令人惊讶的结果,并帮助我们了解了当时 人类面临的生命风险。河流改道形成了圣洛伦佐岛,,该岛位于下夸察夸尔科斯河流域,这是一个低坡度的湿地平原,河流通道往往会在此分岔形成支流。通过对古代河流的识别和排序表明,由于普遍和特定的隆起,圣洛伦索岛周围的河道随时间向外迁移。这些河流为人员和货物往返于岛的节点(运输和通信网络中的独特自然焦点)的流动提供了方向性。水决定着潮湿的沿海平原的生活节奏,水文循环是一种革新力量,为维持不断增长的人口提供了重要的生存资源。

该岛由一个低于2000公顷的山脊组成,四周被河流和湿地包围。圣洛伦佐位于该中心的高处,两端分别设有两个卫星中心。高地被称为高原,是该地的中心部分,周围是多层阶地。它占地150公顷,海拔65米。除了阶地之外,外围是宽阔而起伏的地形,有时与湿地接壤。系统的发掘揭示了行政,仪式,手工艺和上层精英住宅位于高原的高处位置,次要精英的住所以及一些手工作坊在阶地位置,外围是平民百姓的小屋,奥尔梅克文化似乎以类似这样的方式显示出地形上的分区。社会地位反映在人口的空间分布中,因此较高的海拔和较高的中心位置对应较高的地位,而社会地位随着距中心的距离增加和较低海拔而降低。旨在探索家庭空间的大小,形状,建筑风格和组织的发掘证实了这种趋势。例如,具有沙红色赤铁矿地面的结构是出现在高原高处的精英的标记。红色宫殿占地2200平方米,位于高处的中央,顾名思义,用大量红色的赤铁矿进行了装饰。 E组是一个占地1公顷的大型行政仪式区域,其建筑表面为红色,被统治者用来管理首都事务并进行私人和公共仪式,在精心设计的环境中充满了神圣的与起源有关的神话,水,繁殖和冥界的象征符号。

首都的设计——高原,阶地和外围——与神圣山的概念有关。这种宇宙学概念指导着奥尔梅克生活的各个方面,并在圣洛伦佐的建筑环境中得以再现。该文化景观上的人口分布取决于地位和血统,从而加强了社会分化的深刻的意识形态。

我们在圣洛伦佐设计并实施了一个系统钻探项目,以探查该处的垂直尺寸并记录其深埋的地层和结构。超过2600个系统的土壤钻孔穿透了奥尔梅克首都的文化土壤,最大深度为25 m。通过GIS的应用,我们能够:1)重建可追溯到公元前1600年的高原建设阶段。 2)将遗址范围确认为775公顷,并确定最大居民数量为12,000人; 3)确定居住集群的大小,从而确定人口密度;和4)在圣洛伦佐确认了公元前1400年左右城市化的开始。我们证明高原是一个巨大的人工建筑,是用七百万立方米土填筑而成的神圣山的完美复制品。实际上,土的用量大于埃及胡夫金字塔(250万立方米)和危地马埃尔·米拉多尔的丹塔金字塔(280万立方米)。

由于在潮湿热带地区保存条件困难,我们对奥尔梅克手工业的专门化的了解很可能只是数千年前的一些影子。这种环境为奥尔梅克提供了许多资源,但除了极少浸水情况外,这些资源已无法从考古活动中得知。几种商品的手工业生产得到了研究,从玄武岩,黑曜石和沥青等原材料的采购到生产技术和成品的分配,表明了手工业的专门化在位于统治者宫殿内的生产的产品和国内以及非国内制造的商品有所不同。石雕的生产受到严格控制,位于红色宫殿建筑群的范围内,而腹地则生产沥青,接近原材料的供应地,黑曜石叶片由马尔皮卡港的独立工匠生产。还有一个特别的作坊专门用于开采物体,尤其是玄武岩,绿岩,黑色金属和云母制成的名贵物品。

我们对生物的调查主要集中在分析植硅体,花粉,植物大遗存和动物遗存。 奥尔梅克人消费的食物是通过多种方式获得的,包括捕鱼,狩猎,采集,耕种和树木栽培。维持生计的基础包括提供蛋白质的陆地和水生物种,而块茎作物则提供碳水化合物。令人惊讶的发现是,玉米并不是奥尔梅克早期的主要食物,实际上直到公元前1200至1000年才出现在圣洛伦佐的文化序列中。它的历史可能比在数百个分析样品中所观察到的还要久远,但它不是主要的,而是在文化序列的晚期它可能已被用于制作饮料,即公元前1200年之后。

奥尔梅克早期发展的模型强调了以河堤土壤肥力为基础的玉米生产力在圣洛伦佐社会分层发展中的作用。对定居,环境和生存的多学科研究使我们拒绝了该模型,因为除了发现玉米不是维持生计的基础之外,我们还能够证明由于不可预知的洪水,堤坝的耕种产生了可变且通常不可靠的产量。

我们的替代模型基于与根茎作物和水生资源有关的环境风险和粮食生产。水生资源在墨西哥湾沿岸南部的湿地中扩散,而干旱地带则是稀缺资源。水文循环中的波动影响着水生食物来源的可用性及其获取所涉及的风险。风险模型考虑到了粮食生产,环境多样性和水文学方面的局限性,这些是影响可获得的野生和栽培食物的因素。玉米堤坝模型强调平均水平和可预测的收成,而该模型则强调了不可预测的变化所导致的粮食生产极端状况,以及如何通过多样化,储藏,贸易和流动性来管理此类风险。奥尔梅克采取的多样化策略包括在高地上种植块茎作物,在湿地上建造低矮的人工土丘,作为干旱时的基础营地,以开采和保护水生资源。熏制的蛋白质食品对于危机时期的生存至关重要,而大量的蛋白质食品对于建立权力所需的劳动力管理至关重要。

系统化和密集的区域居住模式研究覆盖了800平方公里的低地地形,追溯了该地区不断变化的政治和经济状况,并展示了围绕第一个奥尔梅克首都复杂的多层等级的定居体系的发展。聚落研究表明,公元前1200年至1000年之间的人口增长减少了圣洛伦佐岛上可用于生产碳水化合物的高地数量。这种趋势的后果包括房屋生产,粮食进口以及入侵高风险生态带(如河堤)。

圣洛伦佐聚落模式的历时发展与一千年来的人口增长以及向国家级社会过渡的行政等级制度的形成有关。在顶峰时期(公元前1200-1000年),圣洛伦佐控制了其他五个永久居住点。圣洛伦佐周围的地区面积为400平方公里,拥有20,000名居民。

圣洛伦佐是一个首要的中心,占地775公顷,平均人口为12,000人。它通过整个贸易关系扩大了其在墨西哥湾南部的影响力。在重要的交通枢纽建立次级中心是一项重要的区域扩张策略,其特征是在关键地点存在的石雕。两个这样的地点分别是在该岛的北端和南端的特诺奇提特兰和扎波特山。同样,该岛的南端受该岛的主要入口马尔皮卡港的控制,在那里我们发现了港口基础设施的证据,以及中美洲最早的黑曜石刀片作坊。

奥尔梅克的运输网络由复杂的水路和陆路网络组成,这些网络加强了湿地的经济和社会互动。运输系统以不同的方式配置了沿海平原,这鼓励了孤立的社区融入更大的实体之中,有利于经济专业化和商品的广泛分配。由于运输系统有效运行,因此需要的存储空间较少。河流是最有效的运输系统,因此,奥尔梅克和其他最早的文明出现在河岸边上。

我们对奥尔梅克的运输系统的研究在很大程度上依赖于河流走廊的上下游模型,该模型用于研究东南亚的大河流系统和聚落等级。该模型表明,纪念性建筑的规模与遗址的等级与河流汇合处、河曲以及岛屿处的关键位置相对应。就遗址的重要性和位置,建筑和交通网络中的石雕而言,这种模式在墨西哥南部湾岸的奥尔梅克地区仍然适用。该战略促进了几个层次上的互动,导致地理,政治和仪式景观交织在一起。

我们对区域聚落和雕塑的相关性研究表明,社会,宗教,政治活动和联盟包括圣洛伦佐统治当局的各种参与。首都的皇室统治了卫星中心的较小皇族。偏远地区的精英通过适应其特定社会领域的各种机制参与了等级制度。区域组织将社会和宗族的距离转变为政治等级并将其制度化。这表明存在一个政治行政机构,官方精英的家系在与等级社会形式密切相关的有声望的制度中得到了的仪式上的肯定。偏远的遗址可能通过在仪式中加入石雕来参加周期性的集中式仪式。这种仪式活动通过促进远距离腹地在信仰体系中的横向统一,缔造并保留了精英身份,并增强了融合。它们也是一种手段,可为依赖关系,贸易和社会互动创造途径,并克服或最小化受水文循环影响的社会政治融合以及人员和货物流动的问题。

我们研究的另一个显著目标是对纪念性的奥尔梅克雕塑的背景进行系统,精确的记录和研究,以补充基于形式特征和内在象征意义的解释。在发掘中挖掘出的雕塑,包括最近发现的巨石头像,已经能够根据出土的情境,对这些艺术形式进行图像学的解释。在新的发掘中,对先前发现的雕塑的考古情境进行了重新审查,以恢复和理解背景和时间上的关联。对几十年前发现的巨大石柱的情境的好奇心导致在中美洲发现了第一座统治者的宫殿,被称为红色宫殿。对一个巨大的石制王座和长长的导水管的设置的重新调查发现了一个埋葬着的仪式行政区域,这是中美洲第一个已知的政府宫殿。

显然,奥尔梅克统治者出于政治原因而使用大型雕塑。例如,研究表明,大型王座被重新利用并重新制成巨石头像,以通过将展现权力的王座转化为他母亲的肖像来纪念祖先统治者。然后将这些巨石头像排列成两条横跨高原的巨大线条,形成一个以大广场为界的纪念性展示。由于统治者的倒台和公元前1000年左右首都的遗弃,该展示从未完成。在将它们合并到这个宏伟的场景中之前,一个部分重新建造的大王座和三个未完成的巨石头像被遗弃了。

公元前1000年后,遗址出现的频率和类型急剧减少,表明该地区人口大量减少,约93%。同样,随着人们迁往更远的地区,首都的人口也大大减少。红色宫殿的焚烧和毁灭表明,居民可能是奋起反抗统治阶层无法应对环境变化以及对社会和经济的要求而导致 了不满,饥荒和移民。尽管人口大量减少,但在中古前古典时期仍有少数人居住在该遗址。

前后参与此项合作研究的来自墨西哥,美国,意大利,西班牙和日本的专家和学生。

个人简介

安·赛弗斯是墨西哥国立自治大学人类学研究所的专职高级研究员。她是墨西哥科学院院士。她的主要研究兴趣是中美洲早期文化的发展,尤其是奥尔梅克文明。她对奥尔梅克的跨学科研究推动并形成了由生态,生物学,地貌学,地质学,物理学,人口,恢复和体质人类学领域的国际和国家知名学者组成的研究小组。她的工作以其综合的视角和整体的长期跨学科研究彻底改变了奥尔梅克考古学。她提出的有关奥尔梅克的研究和解释模型享誉世界。她被认为是文明和城市生活起源,古代生产策略,贸易和运输系统研究的权威。她的出版物遍及全世界,是中美洲前古典时期和奥尔梅克文明不可或缺的参考。她是14部科学著作,74篇文章,75本书章节和三卷编辑本的作者。她所获得的奖项体现了她的学术领导才能和国际声誉,例如阿方索·卡索奖,伊利诺伊大学的杰出校友奖,国家地理学会主席奖以及韦拉克鲁斯哈拉帕人类学博物馆奖章。

The Olmec culture arose almost 4000 years ago in the humid tropics of Mexico’s southern Gulf Coast region. Its emergence and early development occurred at San Lorenzo, Veracruz State, between 1800 and 800 BC. During its period of greatest splendor it managed a regional system of communication and transportation crossing the coastal plains and wetlands and established a distinct geo-political territory and regional and long-distance trade systems. Its well-known monumental stone art focuses on themes related to rulers, government and cosmology. Olmec monumental stone sculpture was the materialization of a pre-existing social and political capability to consolidate specialized production and organize the large labor force necessary for the long distance transport of the multi-ton stones from the source area located 60 km away. It also points to stratified social organization and centralized political systems that were sponsored by religion and led by hereditary rulers. Supernatural notions related to water and the underworld comprised the ideological charter of royal descent groups.

San Lorenzo was discovered in 1945 by Matthew Stirling and his wife Marion in the midst of a hot debate about its antiquity and presumed genetic and developmental relationship to the Maya. The next major investigation of the site, directed by Michael D. Coe, who established the antiquity of San Lorenzo, conducted the first stratigraphic excavations, added numerous sculptures to the existing corpus of art and studied the modern environment. Research by the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán Archaeological Project was initiated in 1990 after a long lull in archaeological work in the Olmec region. Its express purpose was to examine relatively unknown aspects of Olmec life and cultural development with a multidisciplinary approach.

Geomorphological studies provided surprising results about the landscape that existed in Olmec times and helped us understand risks for human life. River anabranching produced the island on which San Lorenzo is located in the lower Coatzacoalcos River drainage, a low gradient wetland plain where the fluvial channels tend to divide and bifurcate. The identification and sequencing of ancient rivers shows that the channels surrounded the San Lorenzo Island migrated outward through time due to generalized and specific uplift. These rivers provided directionality to the movement of people and goods to and from the Island node, a unique natural focal point in the transportation and communication network. Water sets the rhythms of life in the soggy coastal plains and the hydrologic cycle is a renovating force that supplies important subsistence resources necessary to sustain growing populations.

The Island is composed of a low 2000-hectare ridge surrounded by rivers and wetlands. San Lorenzo is located on high ground in the center and two satellite centers were founded at each end. The high ground, called the plateau, is the central part of the site which is ringed by multiple levels of terraces. It covers an area of 150 hectares and has an altitude of 65 meters above sea level. Beyond the terraces, the periphery is a broad and rolling terrain that sometimes borders the wetlands. These topographic divisions appear to have been recognized in similar fashion by the Olmec since systematic excavation reveals the location of administrative, ceremonial, craft and elite residential structures on the heights of the plateau, the dwellings of lesser elite and some craft workshops on the terraces and the huts of commoners in the periphery. Social position is reflected in the spatial distribution of the population such that greater altitude and central location correspond to high status, which diminishes with increasing distance from the center and lower altitude. Excavations designed to explore the size, shape, construction style and organization of domestic spaces confirm this tendency. For example, structures with sandy, red-hematite floors are elite markers occurring on the heights of the plateau. The Red Palace, covering an area of 2200 m2, is centrally located on the heights and, as its name indicates, was liberally embellished with red hematite. Group E is a large, one hectare, administrative-ceremonial precinct with a red surfaced construction stage that was used by the rulers for managing the affairs of the capital and practicing private and public rituals in a carefully designed setting imbued with sacred symbolism related to origin myths, water, fertility and the Underworld.

The design of the capital—plateau, terraces and periphery—is related to the notion of the sacred mountain. This cosmological concept, which guides all aspects of Olmec life, is reproduced in San Lorenzo’s built environment. The population distribution on this cultural landscape was determined by status and genealogy and thus reinforced the profound ideology of social differentiation.

We designed and implemented a systematic coring project at San Lorenzo in order to probe the vertical dimension of the site and to document its deeply buried stratigraphy and structures. More than 2600 systematic soil cores penetrated the cultural soils of the Olmec capital to a maximum depth of 25 m. Through the application of GIS, we were able to: 1) reconstruct the construction phases of the plateau dating from 1600 BC; 2) define the extent of the occupation as 775 hectares and determine that the maximum number of inhabitants was 12,000; 3) establish the size of residential clusters and hence the population density; and 4) confirm the beginnings of urbanism around 1400 BC at San Lorenzo. We demonstrate that the plateau is a huge artificial construction, a great replica of the sacred mountain that was built with seven million cubic meters of earthen fill. Its volume is, in fact, greater than that of the Pyramid of Khufu in Egypt (2.5 million m3) and the Danta Pyramid of El Mirador in Guatemala (2.8 million m3).

Due to the difficult conditions of preservation in the humid tropics, what we have learned about Olmec craft specialization likely is a mere shadow of what must have existed thousands of years ago. This environment provided many resources for the Olmec but destroyed them from the archaeological register except for the rare cases of water-logged contexts. Craft production of several types of goods was studied, from the procurement of raw materials, such as basalt, obsidian and bitumen, to the production techniques and the distribution of the finished products, showing that craft specialization varied from attached production located within the ruler’s palace to domestic and non-domestic manufacture of goods. The production of stone sculpture was tightly controlled within the confines of the Red Palace Complex whereas bitumen cakes were produced in the hinterland, close to the supply of raw material and obsidian blades were manufactured by independent artisans at Port Malpica. An unusual workshop was dedicated to drilling objects, particularly prestige items made of basalt, greenstone, ferrous minerals and mica.

Our investigations of subsistence focused on analyses of phytoliths, pollen, plant macro remains and archaeofauna. The foods consumed by the Olmec were obtained with a mixed subsistence economy that included fishing, hunting, collecting, cultivation and arboriculture. The subsistence base included terrestrial and aquatic species that provided protein while root crops supplied carbohydrates. A surprising discovery was that maize did not constitute a principal food for the early Olmec and, in fact, does not appear until 1200 to 1000 BC in the occupational sequence at San Lorenzo. It may have greater antiquity than is observed in the hundreds of analyzed samples but it was not a staple, rather it may have been used for making beverages late in the occupational sequence, after 1200 BC.

A previous model of early Olmec development emphasized the role of high maize productivity, based on the renewal of soil fertility on the river levees, in the development of social stratification at San Lorenzo. Our multidisciplinary studies of settlement, environment and subsistence led us to reject that model because, in addition to the discovery that maize was not the subsistence base, we were able to document that levee cultivation produces variable and often unreliable yields due to unpredictable floods.

Our alternative model is based on environmental risk and food production relating to root crops and aquatic resources. Aquatic resources proliferate in the wetlands of the southern Gulf Coast whereas dry terrain is a scarce resource. Oscillations in the hydrological cycle impact the availability of aquatic food sources and the risk involved in their procurement. The risk model takes into account limitations in food production, environmental diversity and hydrology as factors affecting the availability of wild and cultivated foods. Whereas the maize levee model stresses average and predictable harvests, this model emphasizes the extremes in food production created by unpredictable changes and how such risks can be managed through diversification, storage, trade and mobility. The diversified strategy used by the Olmec included planting root crops on high ground and building low artificial mounds in the wetlands as dry base camps for the extraction and preservation of aquatic resources. Smoked protein foods were necessary for survival in crisis times, and large yields of protein foods were important for the labor management that is required to build power.

Systematic and intensive regional settlement pattern studies covering 800 km2 of difficult lowland terrain traced the changing political and economic situation of the region and showed the development of a complex multi-tiered settlement hierarchy surrounding the first Olmec capital. Settlement studies show that population growth between 1200 and 1000 BC reduced the amount of high ground that could be used for carbohydrate production on the San Lorenzo Island. The consequences of this trend included house-yard production, food imports and the incursion into high risk ecotones such as the river levees.

The diachronic development of the San Lorenzo settlement system is associated with demographic increase over a millennium and the formation of administrative hierarchies in the transition to a state-level society. During the apogee phase, 1200-1000 BC, San Lorenzo controlled five other types of permanent sites. The area around San Lorenzo contained a population of 20,000 inhabitants in a space of 400 km2.

San Lorenzo was a primate center, covering a 775 hectare area, with a mean population of 12,000 inhabitants. It extended its influence across the southern Gulf Coast and beyond largely through trade relations. The establishment of lesser centers at important transportation nodes was an important regional expansionary tactic and was characterized by the presence of stone sculpture at key sites. Two such sites are Tenochtitlán and Loma del Zapote at the north and south ends of the Island, respectively. As well, the island’s southern tip is commanded by Port Malpica, the main entrance to the Island, where we discovered evidence of port infrastructure and the earliest obsidian blade workshop in Mesoamerica.

The Olmec transport network consisted of a complex web of water and land routes that bolstered economic and social interaction in the wetlands. Transportation systems configured the coastal plains in a heterogeneous fashion which encouraged the integration of isolated communities in larger entities, favored economic specialization and a wide distribution of goods. Less storage was necessary because the transportation systems worked efficiently. Rivers are the most efficient transportation systems and, accordingly, the Olmec and other first civilizations emerged on their banks.

Our studies of the Olmec transportation systems rely strongly on the upriver-downriver model of fluvial corridors that is used in the study of the great river systems and settlement hierarchies of Southeast Asia. This model shows that the scale of monumental architecture corresponds to site hierarchy and to key locations at river confluences, meanders and islands. This pattern holds true in the Olmec region of the southern Gulf Coast of Mexico with regard to site importance and location, architecture and stone monuments in the transportation network. This strategy promoted interactions on several levels that led to an intertwining of geographical, political and ceremonial landscapes.

Our correlation of regional settlement and sculptures suggests that social, religious, and political activities and alliances included diverse kinds of involvement of the San Lorenzo ruling establishment. Royal lineages at the capital ruled smaller lineages in satellite centers. Rural elites participated in the hierarchy via assorted mechanisms that were adjusted to their particular social spheres. The regional organization transformed and institutionalized social and genealogical distance as political hierarchy. This suggests the existence of a political administration in which official elite genealogy is ritually acclaimed within a prestige system intimately related to hierarchical social forms. Rural sites may have taken part in periodic, centralized, rituals by including their stone sculpture in the ceremonies. Such ritual activities forged and preserved elite identities and increased integration by promoting the lateral unification of the distant hinterland in the belief system. They also were a means to create pathways for dependency relationships, trade, and social interaction and overcome or minimize problems of sociopolitical integration and the movement of people and goods that are affected by the hydrological cycle.

Another notable objective of our research centers on the systematic and precise documentation and study of the context of monumental Olmec sculpture in order to complement interpretations based on formal traits and intrinsic symbolism. The unearthing of sculpture in controlled excavations, including the most recently discovered colossal head, has led to interpretations of these art forms on the basis of their context, form and iconography. The archaeological context of previously discovered sculpture was re-examined in new excavations in order to recover and understand contextual and temporal associations. Curiosity about the context of an enormous stone column found several decades ago led to the discovery of the first rulers’ palace in Mesoamerica, dubbed the Red Palace. The reexamination of the setting of a great stone throne and long aqueduct led to the discovery of a buried ceremonial administrative precinct, the first known government palace in Mesoamerica.

It has become clear that Olmec rulers used large sculpture for political reasons. For example, studies have shown that the large thrones were recycled and re-shaped as colossal heads in order to commemorate ancestral rulers by transforming their seats of power into their portraits. Then these heads were set out in two huge lines crossing the plateau to form a commemorative display bounding a large plaza. This display was never finished due to the downfall of the ruler and the abandonment of the capital around 1000 BC. One partially recycled large throne and three unfinished colossal heads were abandoned before they could be incorporated into this majestic scene.

After 1000 BC, a dramatic reduction in the frequency and types of sites indicates a substantial population loss, about 93%, in the region. Likewise, the capital suffers a great population decline as people moved out to colonize more distant areas. The burning and destruction of the Red Palace suggests that the inhabitants rose up against the ruler perhaps in response to their inability to cope with environmental changes and the social and economic demands of the elite which opened the way for discontent, famine and migrations. Despite the major population decline, a few people continued to live at the site during the Middle Preclassic.

The collaborators currently and previously involved in this research include the following specialists and students from Mexico, the United States of America, Italy, Spain and Japan: María de la Luz Aguilar, Alejandro Alonso, Virginia Arieta, Nadia Aroche, María Arnaud, Luis M. Alva, Fernando Botas, Joshua Borstein, Elisabeth Casellas, Kong Cheong, David Yiro Cisneros, Robert Cobean, Adriana Cruz, Anna Di Castro, Carmen Durán de Bazúa, Enrique Escobar, José Manuel Figueroa, Nilesh Gaikwad, Rolando Salvador García, Ivonne Giles, Ranulfo González, Lilia Gregor, Louis Grivetti, María Eugenia Guevara, Jennifer Guillén, José Guillén, Esteban Hernández, Sergio Herrera, Alejandro Hernández, Elvia Hernández, Kenneth Hirth, Luis Fernando Hernández, Emilio Ibarra, Gerardo Jiménez, Hirokazu Kotegawa, Marci Lane Rodríguez, Jason de León, Artemio López, Roberto Lunagómez, Arturo Madrid, Brizio Martínez, Enrique Martínez, Timothy Murtha, Ariadna Ericka Ortiz, Fernando Ortega, Mario Arturo Ortiz, María Isabel Pajonares; Rodolfo Parra, Terry Powis, Carolina Ramírez, Isaura Argelia Ramírez, Nicolas Felipe Ramírez, Rogelio Santiago, Stacey Symonds, Jaime Urrutia, Valentina Vargas, Marisol Varela, Enrique Villamar, Carl Wendt, Belém Zúñiga and Judith Zurita.

Biographic Sketch

Ann Cyphers is a full-time, tenured senior researcher at the Institute of Anthropological Research-UNAM. She is a member of the Mexican Academy of Sciences. Her principal research interest is the development of the early cultures of Mesoamerica, particularly the Olmec civilization. Her interdisciplinary research on the Olmec has fomented the formation of research groups composed of recognized international and national academic figures in the fields of ecology, biology, geomorphology, geology, physics, population, restoration and physical anthropology. Her work has revolutionized Olmec archaeology with its integrated perspective and holistic long-term interdisciplinary research. The research and explanatory models about the Olmec developed by her are world renowned. She is considered an authority on the origins of civilization and urban life, ancient productive strategies, trade and transport systems. Her publications have gone around the whole world and are indispensable references on the Mesoamerican Preclassic period and the Olmec civilization. She is the author of 14 scientific books, 74 articles, 75 book chapters and three edited volumes. Her academic leadership and international prestige are manifested in the awards she has received, such as the Alfonso Caso Award, the Distinguished Alumnus Award from the University of Illinois, the Chairman’s Award of the National Geographic Society and the Medal of the Anthropology Museum of Xalapa, Veracruz.